If the images do not appear in due time, please refresh/reload the page.

Architectural Japonisme II

建築のジャポニスム II

1. William Eden Nesfield 2. Irving Gill 3. Bernard Maybeck

4. Christopher Alexander, Kenneth Frampton, and Juhani Pallasmaa

5. Josef Hoffmann 6. Victor Horta 7. August Endell

8. Robert Venturi 9. Wells Coates 10. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Image: Sadanobu, 'Exposition at Okayama Castle', 1879

Uploaded 2024.5.16. Under construction, preview draft, photo captions to be further annotated

William Eden Nesfield (1835-1888)

An Unassuming Japonisme

Including Observations regarding Richard Norman Shaw and Thomas Jeckyll (1827-1881)

and brief mention of James Forsyth (1827-1910)

Yasutaka Aoyama

English architect and designer William Eden Nesfield's japonisme is of a quiet and unobtrusive kind, in contrast to that of a James McNeill Whistler or Edward Godwin, which proclaims loud and clear its affinity to Japanese art. This 'unassuming japonisme' is exemplified in Nesfield's design for Barclay's Bank at Saffron, Walden, built in 1874. At first glance, from a distance, it looks so very English, and not a whit 'oriental'. And yet its facade contains some distinctly Japanese designs, which are also its most prominent and noteworthy decorative flourishes. A Gothic revivalist like many of the late Victorian British japonistes, Nesfield was a collector of Japanese artefacts and aware of Japanese art and design by 1862 (that is, earlier than most artists recognized as influenced by japonisme), according to Anna Bashram in the Brill published Britain and Japan: Autobiographical Portraits (2010).

Nesfield, son of the landscape designer William Andrew Nesfield, studied at Eton where he met Norman Shaw, sharing offices with and working with Shaw from 1863 until 1876 (becoming his official partner in 1866). According to the University of Glasglow's School of Culture and Creative Arts website, "They developed a style which combined elements of the English vernacular with Japanese ornament" ('The Correspondence of James Whistler', www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk). Nesfield, in his use of Japanese designs, like Shaw, while unmistakable when scrutinized, is characterized by a conscious effort not to appear ostentatiously so. Nesfield's dramatically Japanesque byobu screen discussed below, is the exception that proves the rule---his taste for Japan given uninhibited leeway precisely because the screen was made only for the private eyes of the Shaw newly weds.

Toshio Watanabe, a noted japonisme scholar, now at the University of East Anglia, proposes that Nesfield employed 'particular Japanese design devices' while Shaw, after 1862 incorporated asymmetry under Japanese influence. However, this is only half right---because both Nesfield and Shaw employed particular Japanese motifs/patterns; and both incorporated Japanese architectural conceptions of asymmetry, not simply the general idea of asymmetry, but the peculiar Japanese qualities of asymmetry in architecture, not only in terms of plans, but also in terms of elevations, as will become apparent towards the end of this discussion.

We have already discussed the Queen Anne Style in regards to Shaw and Francis Kimball, which we asserted was a style influenced by japonisme, despite its outward semi-gothic appearance, which is generally understood so by architectural historians who specialize in the Queen Anne and other styles of the latter 19th century such as Vincent Scully. Anna Bashram, in her section on Nesfield and Shaw quotes the celebrated architectural historian, former Slade Professor at Oxford University, J. Mordaunt Crook, regarding this eclectic mix of European and Japanese influences:

”Then came Queen Anne, a flexible urban argot, sash-windowed, brick-ribbed, based on late seventeenth-century vernacular classicism, Dutch, French, Flemish, German and English – all seasoned with a dash of Japanese.” (Crook, 1987, p. 170)

An Example of Nesfield's Ornamental Japonisme: Barclay's Bank, Saffron Walden

As for the cranes above the entrance archway, these can be found in various Japanese temple and shrine eave wood carvings across the country, as well as on textiles, mirrors, paintings, lacquerware, and almost every conceivable form of art, as one of the most auspicious symbols of Japan. The reader can surely verify the stylistic equivalence here with Japanese 'tsuru' heron imagery, at his own leisure should he have any doubts.

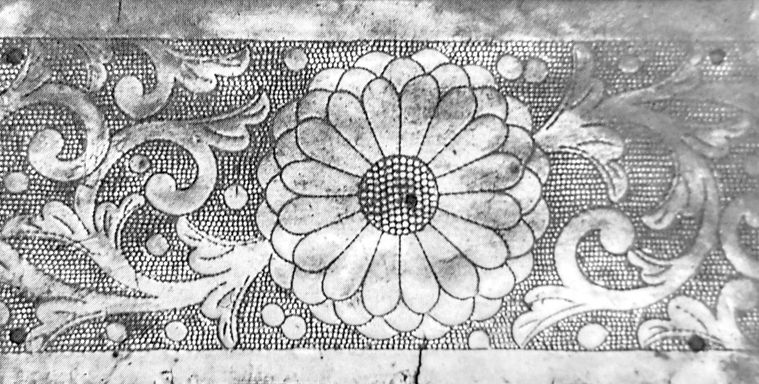

Nesfield incorporated what he described as ‘pies’ into his designs---these too, take directly from commonly found Japanese patterns. But for some reason the one to one correspondence between his pies and Japanese designs is not always recognized, even by well-known japonisme researchers. Some scholars attribute the inspiration for these ‘pies’ to both medieval and Japanese design, which is somewhat puzzling. This author was tempted to leave out the photo captions for the following illustrations, and see if the reader would be capable of recognizing the Nesfield design apart from the rest, so wonderfully does it blend in with the ancient Japanese imperial crests placed above and below it; and also, looking carefully at those designs, to see for himself if there is anything really medieval about them. It would be as if the exact design of the Union Jack were being used by a Japanese designer in the Meiji period, and everyone saying that it was a combination of traditional Japanese medieval designs and also modified British symbols.

(Note: There are Japanese designs, such as those of ranma, that look almost identical to Nesfield's design of alternating and overlapping crests, in groups of threes or fours, with stout wooden section dividers at set intervals between them. Something similar but not exactly alike in the asymmetrical overlapping of circles is the 'tsubo-tsubo' sukashibori (openwork) found at the Ryukeitei (柳慶亭) in Takehara, Hiroshima, transferred from Okayama (originally that of 伊木忠澄), for instance. Unfortunately this author cannot recall the location of the identical pattern or provide a photo to show for it, but hopes that the reader may come across the near identical design one day in his travels to Kyoto.)

Barclay's Bank, Saffron Walden, 1874

Below is a comparison of a Nara temple roof ornament over a gateway whose design has been faithfully recreated over 1400 years, when necessary. Right, brickwork eave ornament, created over 140 years ago by Nesfield.

The use of these flower patterns by those interested in Japanese art in Britain was widespread by the 1870's. Just to offer one example, architect and designer Thomas Jeckyll (1827–1881), whom Bashram considers another "whose work shows substantial Japanese inspiration" and designed with Whistler the 1876 Peacock Room, is known for his wrought iron sunflowers done in a Japanese influenced style. Why is it that not only Nesfield, but so many other European and American architects and designers employed the sunflower? And why in the particular locations and forms they did, such as on the exterior of buildings on higher levels, near the roof and building corners? Why also, in the case of interior ornament, quite often in metal?

The most simple and convincing answer is because that is how it is found in Japan, in its art and architecture. Wherever Englishmen went in Kyoto and Nara (which were popular tourist destinations then as they are today), as well as across Japan as demonstrated by the examples below, they saw the ubiquitous round form of the concentric chrysanthemum in all its subtle variations. For someone Japanese, this pattern is too much part of the built environment to be cognizant of its distinctive nature, but for a visitor it must have been striking As an interior ornament in temples, shrines, castles, or palaces, it was often struck in gold or shining bronze gilt, so it is no wonder it appeared, in all its luminous glory, as a sunflower. But even without visiting Japan, it would inevitably be seen in pictures, Japanese books and English books about Japan, kimonos, obis, lacquerware, swords, armor, mirrors, hina doll sets, and all sorts of other trinkets and objects that were brought over from Japan to England.

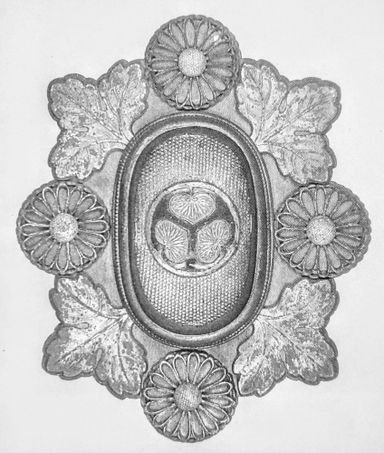

The Omnipresent 'Sunflower' and 'Pie' in Japanese Interior Decorative Metalwork

While the focus of many japonisme researchers has been on the circular monsho, or round family crests as a source for these designs, the inducement to depict that type of design was everywhere, above, around, and below. The following are a few examples of sunflower-like designs from Kubo Tomoyasu's 'Kazari Kanagu' (Ornamental Metalwork), in Nihon no Bijutsu 10, No. 437 (2002.10.15) that give an indication of just how widespread and diverse the applications of sunflower-like designs were, and still are.

1) Kodaiji Temple, Kyoto, Reiya zushi, mini-shrine gilt metalwork decoration (高台寺霊屋 北正所厨子 late 16th or early 17th century). 2) Tsukubusuma Shrine, Shiga, Main Hall, chrysanthemum metalwork ornament (都久夫須麻神社本殿 金具 1602). 3) Zuiganji Temple, Miyagi, Main Hall, flaming (shaped) window metalwork (瑞巌寺 本堂 火頭窓 八双金具 1607). 4) Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, kacho makie raden seigan door hinge (東京国立博物館 花鳥蒔絵螺鈿聖龕 late 16th early 17th century). 5) Rinnoji Temple, Tochigi, tebako box ring for tying string (輪王寺 住江蒔絵手箱 紐金具 1228).

6) Seiganji Temple, Kyoto, sutra scroll box, metal string ring (誓願寺 菊花散蒔絵経箱 紐金具 13th century). 7) Shugaku-in, Kyoto, chrysanthemum shippo fusuma hikite door handle (修学院 菊花形七宝三葉葵引手 1677). 8) Shugaku-in, Kyoto, same 'sunflower'-like hikite detail. 9) Namban chest with round monsho (丸文蒔絵螺鈿洋櫃 late 16th early 17th century, possibly Kyoto or Nagasaki). 10) Musashi Mitake Shrine, Tokyo, Armor with Red Lacing (御嶽神社 赤糸威鎧 12th century). Note the sunflower-like medallions of various sizes in various places on the body armor and helmet.

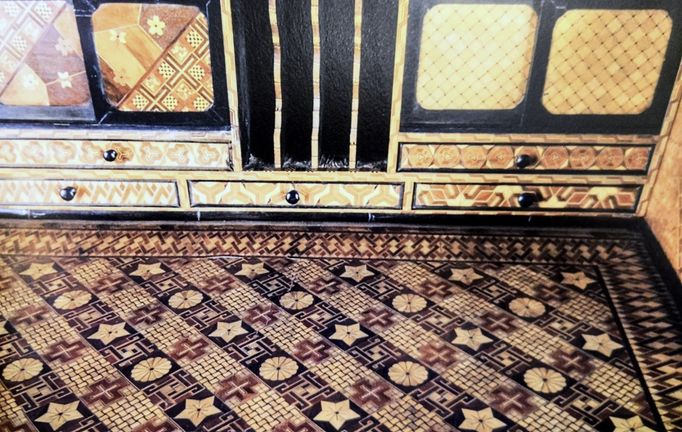

Japanese Export Furniture as an Architectural Design Source

Another likely source of patterns for Nesfield's designs may have been Japanese parquetry, 'yosegi-zaiku' (寄木) patterns on decorative boxes that are truely astonishing in their ultra-fine craftsmanship. These skills were applied to European style desks, shelves, tables, and other furnishings oriented for export to the West, and could not have failed to make an impression on European designers after the opening of Japan and the commencement of trade and expositions from the 1850's onward.

Typical 19th century Yosegi craft designs (a lacquer box also included done in a yosegi style), all from the Siebold Collection: 1) Lacquer kohikidashi (小抽出し) boxes with a combination of geometric, vegetal, and common abstract designs. 2) Yosegi bon (盆) tray, with minute concentric bands of varying abstract designs. 3) Itokoma (糸駒) box decorated with mugiwara-zaiku used to keep shamisen strings. A trick box (仕掛け箱) opened by an an ingenious wood mechanism. Note the 'sunflower' designs on one of the boxes and on the other box how the two different patterns are separated by a diagonal line across the surface. (Photos from 200 Jahre Siebold die Japansammlungen Philipp Franz und Heinrich von Seibold, edited by Deutsches Institut fur Japanstudien, Tokyo, 1996.)

Below are a few examples from the beautifully illustrated booklet published by Lixil Co., Japanese Furniture That Went Overseas: Exquisite Beauty and Delicate Craftsmanship 「海を渡ったニッポンの家具、豪華絢爛、仰天手仕事」(Tokyo: Lixil, 2018). While their exact dates of manufacturer are uncertain, probably somewhere between 1865-1890, they apply traditional designs with the traditional skills of Japanese parquetry from before the 'opening' of Japan.

Japonisme Up Above, Japonisme Down Below

One of Nesfield's most memorable designs is his wedding gift folding screen. Here too, similar motifs of the chrysanthemum as sunflower, and other monsho designs are employed. Other Japanese aspects include of course the panel paintings, being from Japan, and it being a byobu style folding screen with a black urushi-like frame in the Japanese style. Designed by Nesfield, it was actually built by James Forsyth (1827-1910), cabinet-maker and sculptor, who gave it to Agnes and Richard Norman Shaw as a wedding present in 1867. As mentioned earlier, Shaw was Nesfield's architectural partner, and Forsyth a friend of both.

As the Victoria and Albert Museum explains, it is "comprised of 12 panels of paper, painted in watercolour, 6 on each side. These are Japanese, of the late 18th century or early 19th. Carved bands of open fretwork, ebonised and gilded panels, and decorative hinges, all designed by Nesfield and made by Forsyth, complete the piece. Many of the decorative patterns on the screen also appear frequently on Japanese textiles. The repetition of patterns on both sides of the screen suggests Nesfield had access to either a pattern book or stencils used for making such textiles. Motifs include the key-fret (the 'swastika', an extremely ancient motif found in many cultures from the Far East through to Central America), chrysanthemums, spirals, stylised blossoms and daisies, and a roundel containing a bound sheaf of grasses which overlaps a sunflower in a three-legged pot." (https://collections.vam.ac.uk, visited 2024/5/10) However, much more can be said about the specific identities of the individual designs. Even the fretwork above and below the painted panels are reminiscent of Japanese byobu and other furnishings with extensive sukashibori, that were being exhibited at European expositions, such as the Paris Exposition of 1867.

Nesfield (Byobu) Screen, Victoria and Albert Museum

Below is the lower section of the same screen. Again, sunflower type and other medallions, that are identifiable monsho of the kamon (family crest) type are scattered throughout the panel sections. A few select comparisons are provided; but almost every one of them has its Japanese counterpart.

On the second panel from the left is the 1) Sasa-rindo (笹竜胆); and 2) Kokonoe-giku (九重菊). On the second panel from the right is the 3) 'Migi mawari (hitotsu) inenomaru' (右回り一つ稲の丸) with a background of smaller 4) 'hidari mitsu tomoe' (左三つ巴). On the far right panel, partially hidden in the classic kamon overlapping depiction in kimonos, lacquerware, and elsewhere, is the 5) 'Neji onigiku' (捻じ鬼菊), or 'twisting ogre-chrysanthemum'.

The background patterns also take from Japanese precedents, being similar to the Japanese parquetry designs shown above, and are also often used as backgrounds in textiles in combination with monsho crests as in Nesfield's design, though he has sometimes tweaked' them. Nevertheless, they are so fundamentally Japanese and unrelated to the traditional medieval that it is hard to see why certain writers insist on adding that comment (perhaps to dilute the impression of being so heavily dependent on Japanese sources in material, constructional form, design composition, chromatic sensibilities, and specific motifs---but if that is the truth, let us be willing to admit it).

The answer to the question as to whether Nesfield (and all the other best known 'Neo-Gothic' artists and architects) used monsho or other Japanese motifs, is of course, an emphatic yes---he used both monsho and other motifs; taking hints also on how and where those motifs were to be used in his own work.

Observations on the Decorative Motifs of Thomas Jeckyll (1827–1881) in Relation to those of Nesfield

The japonisme of Thomas Jeckyll is introduced in various papers and websites and will not be covered in depth here, only in relation to the work of Nesfield, whose Japanese influence is further clarified by comparison with Jeckyll. Jeckyll is the architect "who excelled in the design of Anglo-Japanese metalwork and furniture." That aspect is clearly presented in the Bard Graduate Center of the Bard College exhibition: Thomas Jeckyll: Architect and Designer (July 17 – October 19, 2003, curated by Susan Weber Soros, founder and director of the Bard Graduate Center and Catherine Arbuthnott, consulting curator). The popularity of the Anglo-Japanese style, of which Godwin is best known for, owed much to Jeckyll as well. As the Bard website explains: "His innovative Anglo-Japanese designs for stoves, stove fronts, fenders, fire irons, and other domestic metalwork were also produced and sold in large numbers." He, perhaps even more so than Nesfield, favored the sort of Japanese floral motifs shown above. "Sunflowers, a quintessential Aesthetic Movement motif, were popularized largely by Jeckyll’s pervasive use of them throughout his career; this emblematic device was featured on a remarkable pair of andirons (1876)." (BGC exhibition website). As for monumental works, his 'Four Seasons Gates, that was first shown at the 1867 Paris International Exhibition and again at the 1873 Vienna International Exhibition, is a fine example of Japanese decorative influence.

Below are a sampling of Jeckyll's stove and fireplace fronts, incorporating Japanese bird designs similar to the tsuru (鶴) and yamadori (山鳥), the stemmed 'chrysanthemum-sunflower', and monsho-like designs.

Like Nesfield and Jeckyll, others of the Aesthetic Movement and Arts and Crafts circle such as Philip Webb and William Morris utilized these Japanese designs, and some of these motifs can be found in the Red House (the sangikuzushi is used rather than the gokuzushi, see article on the Red House on this website). They were popular across the Channel too, and can be found in Auguste Perret's works, for instance, and that of Eugene Grasset in Switzerland (both also discussed on this website). The chrysanthemum, bishamon kikko, sangikuzushi, and seigaiha patterns were especially popular across Europe.

Below: 1) Detail of a Jeckyll designed stove front. 2) Base of monument to Juliana, Countess of Leicester, Church of Withburga (1872) attributed to Jeckyll. 3) Detail of another Jeckyll designed stove front. Jekyll composes the bishamon kikko in diagonal swathes, a technique often used in Japan for textile patterns. 4) Jeckyll grate from photo album, V & A Museum.

Here we have taken up only Jeckyll's use of Japanese motifs as they relate to Nesfield and the wider Aesthetic as well as the Arts and Crafts Movement---of which Japanese art did play a crucial role, despite Morris's harsh denial of it. But in fact Jeckyll incorporated Japanesque designs in his architectural coceptions as well, not only the use of 'Anglo-Japanese terra cotta plaques' at Framingham Pigot (1872), or 1 Holland Park, with its "Anglo-Japanese billiard room and a master bedroom containing some of the most sophisticated furniture ever produced in the Anglo-Japanese style" (Bard Graduate Center at www.bgc.bard.edu, visited 2024/5/11).

Below are some other examples of Jeckyll's use of Japanese motifs and styles. Regard his terra cotta ornament (2) for Lilley Rectory, Hertfordshire (1870-71) of an owl on a pine branch and the print (1) of Utagawa (Ando) Hiroshige also of an owl on a pine branch (1833). Jeckyll uses the classic Japanese stylized way of depicting pine needles, and is why although not specified in the book on Jeckyll from which the picture is taken, it is possible to identify the tree as a Japanese pine with certainty. The owl on pine is a well repeated motif in Japan. Jeckyll's wall scone (3) is extremely similar to ornaments made in the Meiji period, as well as raised metal decoration on the back side of traditional Japanese mirrors.

Below are two pieces by Jeckyll and a typical Japanese tansu cabinet. The 1 Holland Park master bedroom wardrobe to the left (A) is made of walnut with "Japanese lacquer inserts and brass fitings", following the well established European tradition of fitting Japanese lacquerware into European furnishings ever since the 17th century. More importantly, notice the extremely thin drawers in the lower center part of the wardrobe. These are likely to be modeled on tansu cabinet drawers for storing kimonos, which were folded and stored in wide and shallow shelves looking like those of Jeckyll's, rather than hung. So too are the shelves on the upper right in the other Jeckyll cabinet (C) made using parts from his own master bedroom wardrobe (1875). This is a piece which is more completely Japanese in conception, despite not having any obviously oriental looking decorations, in its asymmetric arrangement of shelves of varying sizes and opening methods, swinging doors and pull shelves combined, in its use of simple thick black outlines. And of course it lacking legs, as Japanese tansu, made to be placed on tatami mats without harm to them. An example of a Japanese tansu cabinet (B) combines pull shelves and sliding doors, but often tansu combine pull shelves, sliding doors, and swinging doors. The piece shown here is from the early 20th century, but is done in the traditional style common in the Edo period. (Jeckyll photos from Soros, 2003 by Jean Hotchkis; tansu from Rokusho No. 17, 1995.12.25.)

The above examples by Thomas Jeckyll provide perspective as to just how profoundly japonisme affected those around or associated with Nesfield and Shaw, and how they all mirrored each other to a certain extent in their use of particular Japanese motifs. Jeckyll worked with Whistler, and was acquainted with Dante Gabriel Rossetti. While a competitor of Nesfield and Shaw, Jeckyll and the other two could hardly not have been aware of each other's work, including their shared use of Japanese designs, and as designers of the 'Queen Anne' style. Shaw used Jeckyll designed lamps (Soros 2003, p. 192) that were part of the Jeckyll remodeled 49 Prince's Gate, London (1875-76), which Shaw found "most admirable. I only wish I could have done anything half as good." (Soros 2003, p. 193) Jeckyll was a member of the same clubs as Nesfield and Shaw along with Godwin and Burges (Soros 2003, p. 74). Jeckyll designed a sofa "remarkably similar to a settle designed by W. E. Nesfield in 1868." (Soros 2003, p. 183) At the same time, Nesfield's sunflower must be considered in light of Jeckyll's popularization of the motif in various products sold by Barnard, Bishop, and Barnards. ---All of which points to the growing momentum of the japonisme movement in architectural circles in England during the latter 1860s and 70's.

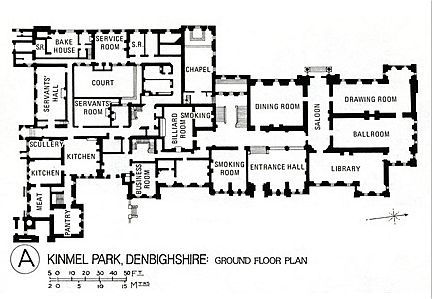

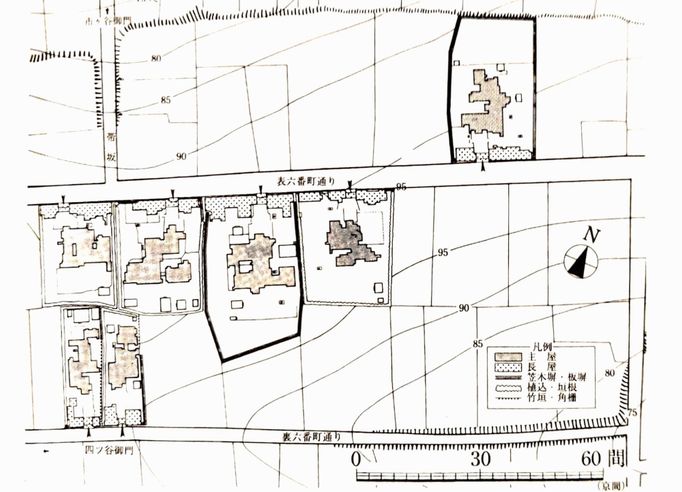

Japanese Style 'Agglutinative' Floor Plans in Nesfield and also Richard Norman Shaw

The Japanese proclivity to let the house to 'wander' with its freely extending floor plan, and to allow each room to have a different orientation in relation to the interior and exterior meant that there was a highly developed individualization, not only of the house as a whole vis-a-vis other houses, but of each room from the others within the same house;---these were important contributions of Japanese architecture to modern conceptions of residential design.

This was thanks to the fact that 1) the master carpenter was also the architect, available to the client for continuous consultation; and 2) the house being of wood elevated from the ground and thus was more easily adaptable to changes; 3) fundamentally of a modular construction and preset sizes for floor and wall panels so that the layout could be tailored to the needs of the individual owner and the lay of the land; 4) symmetry was not demanded and asymmetry the norm. R. N. Shaw's plans for Leyswood (1868) near Withyham in Sussex is of this kind, and like Japanese houses, rooms connect directly to other rooms without or with only minimal corridors, which Henry-Russell Hitchcock calls "one of Shaw's most influential works" in his 'Pelican History of Art' series book on 19th and 20th century architecture. Hitchcock refers to it as the "agglutinative plan", which (though he makes no mention of it) is exactly what the Japanese style of floor plan was, as can be seen from the examples below. Furthermore, woodwork was emphasized to the extent of applying it over solid brickwork at times, along with 'ribbon' type continuous windows, bays also with large window surfaces---all in tune with the quality of Japanese architecture as well.

Assorted Nesfield plans in the "agglutinative" style of the late 19th century

Compare the free extending plans of Nesfield above to that of the Japanese houses below, such as (I) with (i); (II) with (ii); and (III) with (iii). While the plans of the former are moving in the direction of the latter, they still have not reached the more complete freedom of the Japanese agglutinative 'prototypes'. Not shown here is the Nesfield & Shaw plan for Cloverley Hall (1865-8) in Shropshire which is more reminiscent of the freely winding and extending forms of the Ninnaji Temple layout. Even Hitchcock admits there was Japanese influence at Cloverly Hall: "in the detailing of Cloverley there were Japanese motifs, notably the sunflower disks that Nesfield called his 'pies', reflecting the new interest in oriental art that such painters as Whistler and Rossetti were taking." (1958, p. 260)

Assorted Japanese plans of renown buildings from the 17th century

Section of sketches of roof plans and elevations for Lea Wood Hall by Nesfield

Regard Nesfield's roof plan above with the roof of Nijojo Castle shown just below. Compare his elevation sketch of Lea Wood Hall with its varied widths, heights, and asymmetric placement of gables with those of the Muromachi period Ashikaga shoguns' Kyoto Palace of Flowers depicted on a byobu screen painting below right. In Nesfield and Shaw's time, Japan was still a place where most samurai houses and mansions remained untouched and in plain sight for all to see, with their asymmetrically interlocking, multi-shaped and sized gables and hipped roofs, frequently photographed and sketched by early visitors.

It might possibly be asserted that no two houses in Japan that had more than a few rooms were exactly like in premodern times. Below we see a few samurai houses bukeyashi of hatamoto retainers of the shogun who may be characterized as perhaps 'upper middle class' to middle class samurai houses, below that of the great feudal lords and their close retainers, but still above the majority of samurai. Even from the simplified outlines below we can distinguish they are clearly different from each other in their configurations. That striking individuality was something that any Western architect with finer sensibilities could not fail to miss, and which Nesfield's varied, asymmetric house plans seem to aspire to.

We have discussed how Japanese art and architecture did have an impact on the British architectural scene; that japonisme was a shared passion by leading architects of the day, who competed and often copied aspects of each other’s designs, including those inspired by Japan. If we think about it under the clear light of day, would it really have been possible for it to be otherwise, for the best known painters, graphic designers/illustrators, writers, ceramicists to cutlery makers, and eventually the general populace to have been swept up in the japonisme craze, and only somehow architects not so?

We must be leery of comments like those of Hitchcock, who goes out of his way to say: "But japonisme, though a major contemporary theme in the arts, influenced Shaw and other architects very little." Indeed, Hitchcock mentions Japan very little, even when he certainly should. Not a word of it in the case of Richardson; McKim, Mead & White; Horta; Guimard; or Mackintosh; for example, where other biographers have been of the opinion that a meaningful Japanese influence clearly did exist in the works of those architects.

This unfortunate silence or naysaying of Japanese architecture is somewhat of an ongoing tradition among mainstream historians and prominent men of society, starting with J. Rutherford Alcock, who flatly declared Japan had no architecture, and reinforced by G. B. Sansom in his Japan: A Short Cultural History (revised edition, 1952), "acclaimed by critics as the best historical study of Japan in the English language" and commonly found on bookstore shelves even into the 21st century. There Japan is in essence portrayed as a monotonous imitator of China or the West; and as for Edo period art, which was the basis of much of the japonisme movement, he says brazenly:

"...in the arts alone there is not much to record. The old forms continued, rather lifelessly, in building, painting, and poetry... It is curious that the growth of a great city like Yedo should have failed to stimulate architecture, yet certainly there is nothing in either early or late Tokugawa times which calls for high praise. The most important palaces and mansions were uninspired copies of Momoyama types, and in shrines and temples there was a preference for gongen-dzukuri, an uninteresting style exemplified in such buildings as the Zenkoji of Nagano. The most celebrated architectural monuments of the Yedo period are the great mausolea of the Shoguns at Nikko. Technically these are debased forms of gongen dzukuri..." (page 478, italics in bold added)

That someone making such unsubstantiated assertions (and who hardly ever provided citations) can be feted as a great scholar, East and West, is something of a mystery; and that without any objections from his peers then nor scholars today is troubling; perhaps they have been inclined to dismiss them as the ramblings of a superannuated emeritus. Only that it is this sort of deprecation or otherwise egregious omission regarding Japanese art among authoritative sources like Sansom, which is partially responsible, if only indirectly, for the callous treatment of traditional architecture in Japan by the Japanese themselves, whose destruction (besides the most historic monuments---almost daily I see another traditional house being torn down in Kyoto and replaced by a small-windowed, prefabricated type of Western style house) has been justified precisely by the attitude fostered by such opinions, it being a nation which has been so heavily pressured to accept Western value judgements. We are not talking about the minority opinion in the West that comes to Japan and is so often interviewed in Japan, but the attitude among opinion leaders and in books by academics that never visit Japan on both sides of the Atlantic, who guide orthodox views on artistic value and merit. So too are these widely disseminated opinions to thank for the general ignorance regarding Japanese artistic influences worldwide. Let us then set the record straight, rewriting Sansom's lines closer to a better informed opinion:

"...in the arts alone there is too much to record. The old forms continued, full of zest, in building, painting, and poetry, developing new forms as well, seen in the ukiyo-e of Moronobu and the haiku of Basho. It is inevitable that the growth a great city like Yedo should have greatly stimulated architecture, and certainly there is much in early to late Tokugawa times which calls for high praise. The most important palaces and mansions went beyond the Momoyama types, as seen in the full development of the asymmetrical Sukiya Style, and that of the subtle Katsura Villa as well as the castle landscape designs of Kobori Enshu. And in shrines and temples there was no single preference for gongen-zukuri, though there too masterpieces of that style were built, exemplified in the exquisite symmetricality of Zenkoji, Nagano. For Western eyes, the most celebrated architectural monuments of the Yedo period may be the great mausolea of the Shoguns of Nikko, which exhibited a heretofore unmatched form of ornamented gongen-zukuri; yet the true achievement of Edo period architecture was in the astonishing regional diversity of residential styles, both of the city and country."

Bibliography

Bard Graduate Center. At https://www.bgc.bard.edu/exhibitions/exhibitions/44/thomas-jeckyll.

Basham, Anna. 'The Changing Perceptions Of Japanese Architecture 1862–1919'. In Hugh Cortazzi (ed.), Britain and Japan' Biographical Portraits, Vol. VII, Brill ebook, 2010, pp. 487–500.

Crook, J. Mordaunt. The Dilemma of Style: architectural ideas from the picturesque to the post-modern. London: John Murray, 1987.

FurusawaTsunetoshi (古沢恒敏 ed.) Monsho Daishusei (紋章大集成). Tokyo: Kinensha (金園社), 1970.

Irohakamon at https://irohakamon.com.

Nihon Kenchiku Gakukai. Nihon Kenchikushi Zushu. Shintei dainihan. Tokyo: Shokokusho, 2007.

Tomoko Sato Tomoko & Watanabe Toshio (eds.) Japan and Britain: An Aesthetic Dialogue 1850–1930. London: Lund Humphries, 1991.

Toshio Watanabe. High Victorian Japonisme. Bern: P. Lang, 1991. p. 170.

Soros, Susan Weber and Arbuthnott, Catherine. Thomas Jeckyll: Architect and Designer, 1827-1881. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003. An excellent book, but it has a pronounced tendency to designate designs that are clearly of Japanese origin, or may have parallels to Chinese designs but are very likely to have been modeled on Japanese examples, as Chinese. It provides Chinese artworks or images for comparison with Jeckyll, but no Japanese artworks. Hopefully this article will make up for that shortcoming in what is otherwise an iluminating and valuable resource on Thomas Jeckyll.

__________________________________

Uploaded 2024.5.17. Under construction; preview draft, photos to be annotated and text to be revised and added.

Irving John Gill (1870-1936)

A Japonisme of 'Severe Elegance'

Irving Gill is a lesser known but pivotal figure in the history of modern architecture in the United States. Born in Tully, a small town in the countryside of New York state, south of Syracuse, he joined the firm of Adler and Sullivan in Chicago, where he worked with Frank Lloyd Wright, and later moved to San Diego as an independent architect. Gill was close in many ways to Adolf Loos, in the appearance of his designs and his emphasis on functionality and his anti-ornamentalism.

And like Loos, what is rated as his better work, such as the Dodge house of 1915-16 (originally at 950 North Kings Road in Los Angeles), or the Scripps house (1917), at La Jolla and now a museum, were distinguished by the prominence of their Japanesque qualities, though the Scripps house is now so transformed that all vestiges of the original interiors are but gone. Even Henry-Russell Hitchcock conceded a strong Japanese aspect to his work:

"Gill's interiors are especially fine and also quite like Loos's. Very different from the rich orientalizing rooms designed by the Greenes, they are in fact more similar to real Japanese interiors in their severe elegance. The walls of fine smooth cabinet woods, with no mouldings at all, are warm in colour, and Voysey-like wooden grilles of plain square spindles give human scale. The whole effect, in its clarity of form and simplicity of means, is certainly more premonitory of the next stage of modern architecture than any other American work of its period." (The Pelican History of Art: Architecture: 19th and 20th Centuries, 1958, p. 454)

As we have already discussed (see article on Voysey in the preceding 'Architectural Japonisme', part I), those Voysey-like grilles are most likely derived from Japanese senbonkoshi 'thousand stick grills', of which examples have also been provided in the articles on Alvar Aalto. And it should be no surprise that Gill would incorporate Japanese designs into his projects, as after all, not only was the Hooden still standing in Chicago for all to see; he worked with Frank Lloyd Wright for years, who had a deep interest in Japanese art and architecture from that time which he certainly must have conveyed to Gill in one form or another.

Built in storage such as that above, whether cabinetry or closets for bedding and the like, is one of the key and original concepts of Japanese interior design, and has been adopted by many designers around the world. Gill combines such ideas with other Japanese architectural qualities such as simple rectangular and fine spaced wooden grillwork shown below, smooth white walls combined with broad unpainted wood surfaces, ranma like vents between rooms, asymmetric floor plans, and a general simplicity and cleanliness of design.

In Japan, finely spaced grillwork was omnipresent outdoors and indoors: on exteriors as in the ukiyo-e print below left, as well as ubiquitous in interiors, as seen on the Nishihonganji Temple doors on the right. Gill's grillwork, center, shares the proportions and sense of spacing of that found in Japan.

Below to the right is Hirokage's Edo meisho doke zukushi, Naito Shinjuku, mid-19th century. It is a comic scene of a horse kicking up a tray of goods into mid-air. What is of interest to us here is the grille-work in the background which continues from unit to unit creating a dazzling effect of almost infinite continuity. As in Gill's interior to the right, the grille-work is combined with simple, rectangular spatial volumes with uncluttered wall surfaces, with neither base nor crown mouldings, and large rectangular openings connecting it to other spaces, though Gill has inserted an arch form within it.

We have spoken first of the interior, whose Japanese qualities are easier to recognize. The exterior of the Dodge house at first glance does not have any stereotypically 'oriental' features. The elevation is in plain white with little ornamentation to speak of; yet its asymmetric elevation, its room to room right angle bending floor plan, and its austere garden with stone like bushes on a textured pavement-like surface does evoke a sense of Japanese architectural aesthetics and rock garden design.

Gill's 'Craftsman' and 'Prairie' Styles as Inspired by Japanese Carpentry and Craftmanship

Some of his earliest works are more Japanese looking even on the exterior, such as his Craftsman and Prairie style houses. For example, the first house he built in La Jolla (now part of San Diego), and perhaps the first Craftsman home in California, was the Windemere Cottage (1894) shown below, but was sadly demolished in the 21st century (as is the fate of most outwardly 'Japanesque' homes in America). The photograph of it below, circa 1910, was taken when it was located on Prospect Street, its original location (La Jolla Historical Society Collection). His designs of this early period (1894-1905) reveal their Far Eastern influences more straightforwardly than do his latter works.

Windemere Cottage, 844 Prospect Street, La Jolla (built 1894, transferred 1927, demolished 2011)

Others have already documented the key role that Japanese models of carpentry and craftsmanship provided for the Craftsmanship Style in California, which we will not delve into depth here, and is discussed in the articles on Greene and Greene on this website. Suffice it to quote A. McCausland in her 'California Craftsman architecture: an interactive historical database' (Sacramento State University, 2015), who, touches upon some key points in the background and development of "strong Japanese influences in the California Craftsman style":

"George Turner Marsh, a native from Australia, opened America's first shop devoted exclusively to Japanese Art at San Francisco's Palace Hotel in 1876. Marsh also designed a Japanese garden, a two-story gateway called a “romon,” a “bazaar,” a small theater, a two-storied dwelling called a “zashiki,” and several open shelters for the California Midwinter International Exposition in 1894. The area survives today as the Japanese Tea Garden in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, the oldest of its kind. The World’s Colombian Exposition in Chicago also featured Japanese traditional architecture, which influenced the noted Greene brothers. Many world fair expositions and their Japanese architectural exhibits influenced the Craftsman style in the United States, as is made apparent by the heavy Japanese qualities of many California Craftsman houses." (p.10)

Irving Gill is but one example we have raised here to provide an inkling of what was a widespread interest in Japanese architectural craftsmenship among leading architects of the early 20th century in California, and elsewhere in the United States.

The Marston block of Gill Designed Houses in San Diego

Gill working in partnership with William Sterling Hebbard, designed several houses in 1905 on Seventh Avenue, in San Diego on the northwest corner of what is now Balboa Park, also in what might be called a Craftsman or Prairie style, with a strong Japanese flavor to it.

Alice Lee House, 7th Avenue, San Diego

The above photo is from the AD&A Museum of the University of Santa Barbara, California website (http://www.adc-exhibits.museum.ucsb.edu), which which provides the following explanation: "Alice Lee (a San Diego socialite and second cousin of Theodore Roosevelt’s first wife) and Katherine Teats commissioned two distinct house groups from Gill. In 1905 Gill designed a house for Lee and Teats on Seventh Avenue, with adjacent rental houses, all in the Prairie style, on land purchased from George Marston, another client who built a significant house nearby, currently a museum and historic landmark. Hazel Waterman, then working in Gill’s office, did the drawings."

The landscape was by the renown gardener and botanist Kate Sessions, seems to had some kind of affinity to oriental gardening, as can be inferred from the photo above in the stone lined paths and their winding, irregular shapes, and the diagonal approach to the house. The impression one receives from the period photographs, with the streets unpaved and the upper stories of the houses with open air rooms with ample cross-ventilation also reminds one of Japanese house construction; indeed the cluster of these homes with their long sloping eves and the emphasis on uncluttered perpendicular angles for the facades, in clear outlines, must have exuded a rather exotic, Far Eastern atmosphere, almost like a transplanted village from overseas (Photos: Art, Design, & Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara).

Katherine Teats Cottage, 7th Avenue, San Diego

Note in A) the very shallow, rectangular bay window with extending eaves forward and to the sides, and though not visible, with wooden supporting and protruding members visible at the bottom, much like Japanese bay windows. B) Here the idea of a Japanese covered second storey room is evoked, where the 'taruki' (supporting wood sticks perpendicular to the wall surface) of the eaves are clearly visible. C) The thin partition like walls framed in wood, the delicate square grilled doors, the round lamp, the built in shelving; all these elements form a set constellation of characteristics that are shared with Japanese architecture.

Marston House, 7th Avenue, San Diego

Gill in 1904-1905 also designed the Marston House (for George W. Marston), along with the Alice Lee, Katherine Teats, and other houses on the same block. The Marston House, like the Alice Lee House, has aspects that convey an exotic impression. In particular, the projecting house extension, with its bent, flaring roof, shown left (a) and from a different angle (b), is reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright's similar extension on the Harry C. Goodrich house, Oak Park, Illinois (1896) that Kevin Nute discusses in his American Institute of Architects prize winning Frank Lloyd Wright and Japan: The Role of Traditional Japanese Art and Architecture in the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright (2000, p.65). There, Wright modeled his extension from a part of the Hooden at the Chicago World Fair of 1893 (World's Columbian Exposition). In Gill's design, however, the separation from the main structure even more pronounced. Reviewed from a certain angle, higher above on the slope, one receives an odd sensation of being in Nara Park in Japan, where ancient buildings with similar roofed buildings dot a gently sloped and comfortably treed landscape; only the deer are missing.

Inside the house (c), the layered sliding partitions, the thick rectangular beams which jut down from the ceiling, and those running along the length of the walls, are almost Japanese, in their 'hari' beam and ranma proportions, giving the interior (putting the furnishings and decor aside) a noticeably Japanese atmosphere.

Bibliography

Under construction

Hines, Thomas S. Irving Gill and the Architecture of Reform: A Study in Modernist Architectural Culture. New York: Monacelli Press, 2000.

Donaldson, Milford Wayne. 'Irving Gill California Architect'. Broadcast talk on KOCT (TV, North County, San Diego), 2018.8.29. A desire to connect Gill to various great names in Western art, with no mention of Japan whatsoever. Nevertheless, informative, by someone who clearly is a passionate admirer of Gill. Shows some sketches/paintings of Gill, somewhat reminiscent of byobu art, often with yellow backdrops, including panoramic city scenes, almost a rough, architectural version of the rakuchu rakugai zu genre of byobu painting.

Levitan, Corey. 'Deep-Sixed: The Top 6 architectural losses in La Jolla history'. La Jolla Light, Sept. 25, 2019 12:01 AM PT at https://www.lajollalight.com/lifestyle, visited 2024.5.17.

Streatfield, David C. 'The Evolution of the California Landscape'. Landscape Architecture Magazine, Vol. 67, No. 3 (May 1977), pp. 229-239.

__________________________________

Under construction, preview, photo captions to be provided.

Bernard Maybeck (1862-1957)

Japonisme Blossoming Through a Dense Eclecticism

Yasutaka Aoyama

Who is and where does Bernard Maybeck stand in the history of American architecture? Maybeck is difficult to pigeon hole; one authority on American architecture called his work defying classification, probably something that would have delighted the "mischievous Maybeck" (Koeper, 1981, p. 315). He designed the well-known Palace of Fine Arts (1915) in San Francisco and contributed to the design of the University of California at Berkeley (1899). A colorful figure, and of importance, we look at what role, if any, and in what way, Japan played in the making of his architectural designs.

Of early 20th century American architects, most would agree Frank Lloyd Wright towers above the rest, and regarding the profound influence of Japanese art and architecture upon Wright, besides himself baring his breast on the subject, that influence has been thoroughly documented by Kevin Nute in his award winning treatise, Frank Lloyd Wright and Japan (2000), mentioned in previous article. After Wright, the trio of Greene and Greene, Irving Gill, and Bernard Maybeck are usually considered to be the three most important names in American architectural history for the first decade and a half or so after the turn of the century. Greene and Greene and Irving Gill have been already discussed on this website; there remains only Maybeck, whose japonisme is quite evident, clearly manifested especially in his most celebrated work, the Christian Science Church on Dwight Way, Berkeley, California (1910)---and yet goes mostly unmentioned.

Perhaps it is the dense eclecticism that is ‘planted’ around and within that clouds the view. Yet despite the growth of Neo-Gothic and Romanesque wood, concrete, and metal, fluted neo-classical square columns (though with figures on the capital), Byzantine lamps, Arts and Crafts type colored geometric exterior decorations along with an assorted medley of other stylistic insertions---his japonisme is still in plain sight, if one simply opens one's eyes to it.

A typical description of the building is found in William J. R. Curtis' Modern Architecture since 1900 (3rd edition, Phaidon, 1996, p. 96): "...a jumble of styles and allusions---Gothic, suburban California, Stick Style, Japanese, and an almost fantastic range of materials and effects" or Frederick Koeper in American Architecture Volume 2 1860-1976 (MIT, 1981, p. 315): "a free mixture of Oriental, classical, Romanesque, and Gothic motifs all combine to produce one of the most unusual monuments in America." The specifically Japanese influence is mentioned last if at all; but if anything, it is the root concept of the work---the underlying schema---as well as the source of many of its most striking and captivating forms, without which it would be reduced to simply melange of familiar elements.

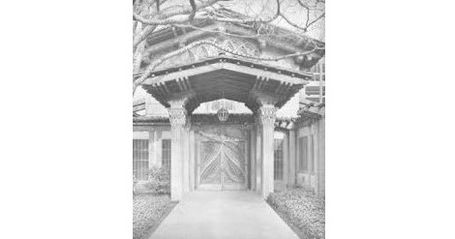

Take for instance, the first impression one receives on approaching the Church. It is the spreading, multilayered roofs, combined with wisteria racks in front, which give it its unique appearance. Both these elements have Japanese precedents: the roof form from Japanese religious architecture found in temples and shrines; the wisteria racks, called 'fujidana' found often in combination with residential or religious architecture, often in the form of a passageway. Below, next to photos of the Maybeck designed First Church of Christ, Scientist (Christian Science) in Berkeley, an example is provided of a Buddhist temple with wisteria (estimated age 400 years) racks in front---Teishoji (禎祥寺), in Saijo City (西条市), Ehime Prefecture.

A Constellation of Japanese Architectural Elements and Ideas

Like his eclectic use of a variety of different styles from different epochs, so even in his use of Japanese elements, he mixes a variety of secular and religious, or otherwise monumental and residential, forms of Japanese architecture in his works. Below, exterior and interior aspects that utilize Japanese architectural concepts and forms. Compare the exterior appearance of the Church especially its roof and conception of pergolas spreading out to the sides in (1) with that of Tosa Jinja (1570) in Kochi Prefecture shown in photos (A) and (B) further below.

1) Maybeck's First Church of Christ, Scientist, view of front entrance with Japanese style and angled interlocking roofs and grille-work spaced and divided in typical Japanese residential and shop style (Please take a walk down any street in Kyoto or Kanazawa or for that matter, any old town in Japan should reader have any doubts). Echoes of that can even be found in the grille rails surrounding Japanese shrines and in their open halls shown below in (A) and (B).

2) This looks as if straight from a Japanese interior, though wood has been replaced by modern materials. Description provided by Cardwell: "Skylights, translucent windows, and relfections on glass modulate the light in the entrance passageway. The use of industrial steel sash reveals Maybeck's genius and willingness to use modern materials even going contrary to the manfacturer's own opinion of the suitability of the material." Not one word about the obviously Japanese aspects of the entire prospect, from the exposed overhead hari style beams, to the classic shoji style window and panel grids on both sides. Especially the shoji doors to the far back---these are identical to the Japanese 'fujimi shoji' (富士見障子) or 'Mt. Fuji viewing shoji' with a 'katabiki' (片引き) sliding part to the window within the window, or if slightly lower positioned, then called a 'yukimi shoji' (雪見障子) i.e., 'snow viewing' shoji; or otherwise when fitted with a clear glass window known as a 'tategaku-iri shoji' (竪額入り障子), that is shoji with square frame inserts for windows or small opening sections within the larger sliding door.

Below: a) Christian Science Church, Berkeley, pergola with kura stye doors. b) Church exterior view of windows and eaves. Not only the windows in full view, but the way they are combined with a wall with clerestory grilled windows to the left, and the small second level half gable and other roofs narrowly spaced, and at different angles, with Japanese style eave woodwork visible on the small crossways chimney-like roof in back. c) Church exterior pergola, reminiscent of a Shinto shrine's open to the exterior, pergola-like hallways. Compare with the Tosa Jinja pergola above; in Maybeck's design, even sculptural substitutes for the stone toro, or lantern stand near the Church pergolas. (Photos UC Berkeley, Barncroft Library)

Incorporating a Japanese Sense of Roofing Aesthetics

(I) A structure that evokes secondary gateways and roofed structures in front of and around the main halls of Japanese temples and shrines.

Even the gothic style glass windows under the eave seen in (II) with their curving designs at the top and latticework below may be said to correspond to the curving 'gegyo' ornaments and 'hishizama' grillwork found in the gable eaves of Japanese temples and shrines. We can also see structures which correspond to 'keta' supporting boards and the keta kakushi (keta caps) under the roof of the Church. In the photo to the right, of the exterior walls of the Church (III) we find wooden structures similar to 'tohshi hijiki' (通し肘木) in Japanese religious architecture.

Consider the above images of the Christian Science Church with once again those of Tosa Jinja below. To make things simple, and to show that many of the details of Maybeck's Christian Science Church can be found as an assemblage in one Japanese shrine or temple, we have taken examples mainly from Tosa Shrine, though more similar looking structures to the Sunday school gateway (I) above could be found at other shrines than that offered below (i); another Tosa structure similar to the Sunday school gateway is the small roofed structure in front of the Shrine in (A) shown earlier. Compare also the flaring roof aspect of (II) with (ii); and the Church crisscrossing wood beams in (III) with the diagram of Japanese temple/shrine eave wood construction (iii).

Below left: exterior, view of structure from elevated location. Tosa Jinja, Kochi, aerial view of structure. The Tosa Shrine is also a basically open air structure in front, with a similarly wide, gentle sloping roof supported by pillars, while in back, taller, structures with roofs of varying heights are partially visible. To the sides, corridors, in the case of the Church pergolas, while those of Tosa Jinja are roofed, giving an impression of permeable, open air spaces spreading to the sides.

And elsewhere too, one finds a Japanese or other Asian forms in Maybeck's roof designs. Below left: an agglomeration of Eastern style roofs perhaps more similar to those of Katmandu than Kyoto, but again, no mention of Nepal or Japan, or of anything east of Rome in Cadwell's book. Right: Japanese shrine and temple style eave woodwork including heavy sasu (叉首) crossbeams, flat ended taruki (垂木), 'boat style' (船肘木) funahijiki and other hijiki (肘木), and kibana (木鼻) nosings. There may be much more that is even more clearly oriental looking in Maybeck's work, for the photos below are from Cardwell (1977) who makes no mention of Japan at all in his book on Maybeck. It is left to future researchers to make a thorough investigation of the complete oeuvre of Maybeck, in light of the heretofore downplayed or ignored role of Japan and other areas of Asia in commentaries of his work.

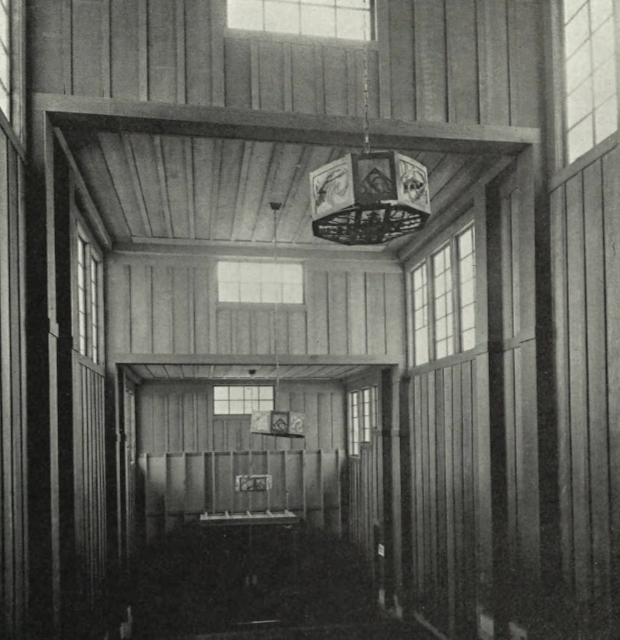

Simulating a Sense of Japanese Country Interiors

1) Town and Gown Club, Dwight Way, Berkeley, 2nd floor (1899). Japanese country house style, exposed beams, Japanese or Chinese lamps or look alikes. Japanese style lighting seems to be one of the themes of this building; elsewhere too, there are residential or Japanese inn style lighting fixtures (see page 63). 2) Albert Schneider House, living room Arch Street, Berkeley (1907). Perhaps closer to a Japanese farmhouse than a Swiss chalet with kakejiku reminiscent pictures, that is vertically long pictures reminiscent of sumi-e paintings on hanging scrolls. 3) Hotel at Clyde, Clyde, California (1918), by G. A. Applegarth as architect and Maybeck as supervising architect. Though the exterior resembles Tibetan-Bhutanese architecture more than Japanese, the interior is like that of an old Japanese country hotspring bath house, or onsen with clerestory windows and vertical wood plank walls, only that Japanese hakkakei (octagonal) lamps have been added. 4) House of Hoo Hoo, Pacific Lumberman's Association, San Francisco (1915) with a kicho (几帳) like multistrip cloth to veil the goshintai (御神体) object of worship beyond. Perhaps a play on the name of the Chicago Exposition of 1893 Hooden, the Japanese pavilion---in any rate, definitely oriental sounding.

Elsewhere at Berkeley, built-in furnishings, as in the Lillian Bridgman House, the stairway area of the Charles Keeler Studio or the G. H. G. McGrew House all exhibit a strong affinity to traditional Japanese residential, especially country architectural aesthetics. One finds even intimations of Gassho zukuri interiors in his Outdoor Art Club in Mill Valley. (Photos from Cardwell, 1977)

And while his exposed wooden constructions are often assumed to derive from medieval or Swiss chalet forms, they better compare with Japanese farmhouse construction in their angulation and thoroughly exposed wood member designs, as well as their interior decor conceptions with objects hanging noticeably from the beams. Below a diagrammatic section of a 'gassho-zukuri' (合掌造り) style farmhouse to the left compared with Maybeck's interior of the Outdoor Art Club, West Blithedale Ave. in Mill Valley (1904), right. Also of interest on the roof of the Outdoor Art Club are udatsu (卵建)-like structures.

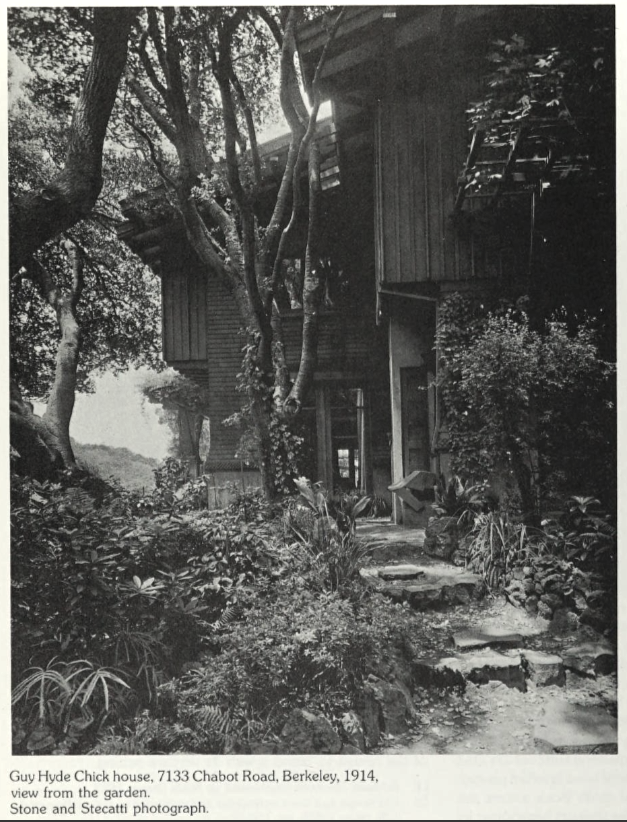

Evoking a Japanese Sense of Rustic Serenity

Left: The Maybeck designed James Fagan House (1920) in Woodside, with its Japanese country style mon (門) gate. Right: The Guy Hyde Chick House and garden (1904) in Berkeley, with its irregular stone steps much like in in a Japanese garden. The house has on the second floor exterior, door pocket 'tobukuro' (戸袋) type wood paneled overhanging structures made of vertical wood panels as in Japan. In Japan these contain the sliding amado (雨戸) rain doors placed at the ends of the windows or corners of a house. (Photos from Cardwell, 1977.)

Compare the above photos of Maybeck structures with those of Japan below, (A) with (a) and (B) with (b). The Sasagawa House of Niigata City was originally built in the 17th century; after a fire in 1819 it was rebuilt in 1826. It's gate (a) shown below, unburned, is from 1573-1591. As for (b), a much closer analogy could surely be found in Japan, but even this old photo of the Ashinomaroya (あしの丸屋) house of the poet Matsunaga Teitoku (松永貞徳), Jissoji (實相時) Temple, Kyoto, conveys the sense of Japanese rustic serenity that Maybeck tried to capture.

The Laura G. Hall House (1896) and Gogenzukuri à la Americana

The Laura G. Hall House (1896) at 1745 Highland Place, Berkeley (occupied first by Laura G. Hall for a year, and after that for decades by J. Stitt Wilson) was unfortunately demolished in 1956. The few photos that remain, and the plans, reveal intriguing similarities to gongen-zukuri (権現造) style shrine-masoleums in Japan of the 16th century. Compare the photos above with those below; note how the facade of the Hall House parallels that of the Ueno Toshogu (上野東照宮 1627) in Tokyo: the flaring roofs with pronouncedly extending eaves; the roof line more vertically angled in the central part, and then at a markedly less inclined angle towards the edges; the clearly outlined bracketing of the center, projecting forward, comprised of three upright rectangles, in the case of the Laura G. Hall House as window frames, in the case of the Ueno Toshogu windowless frames, in both cases emphasizing the symmetry of the design. Even the seemingly out of place, pointed, centrally placed gable of the Hall House, perched on top, might look like a European style addition, but in fact, its placement there, is reminiscent of the chidori hafu (千鳥破風) that sits on the Ueno Toshogu roof, dead center, visible in the photo below. To the right of the Ueno Toshogu photo (the plan for it not readily available) are two examples of gongen-zukuri floor plans: that of Rinnoji Temple ( 輪王寺), Taiyuin reibyo (大猷院霊廟 1653) for Shogun Iemitsu and the Nikko Toshogu Shrine (日光東照宮) Gohonsha (御本社 1617) for Shogun Ieyasu. The Laura G. Hall House also had a stepped level type structure, as is sometimes the case with gongen (e.g. Myogi Jinja 妙技神社) or kibitsu (吉備津)-zukuri type layouts.

__________________________________

Uploaded 2024.5.22 Preview

Japonisme in Late 20th and Early 21st Century Architectural Theory

Speaking of the East in Veiled Terms

The Timeless Way of Building (1979) by Christopher Alexander

Studies in Tectonic Culture (1995) by Kenneth Frampton

The Eyes of the Skin (2012) by Juhani Pallasmaa

A discussion of popular architectural writings in the latter 20th century showing the continuing influence of Japanese architecture at that time. While there are direct references to Japan in these works, it is the use of substitute phrases, such as Christopher Alexander's 'Timeless Way' which for all intents and purposes is a proxy for philosophical conceptions of the Dao/Tao (道) and Zen. And his effort to create a comprehensive 'Pattern Language' (written with Sara Ishikawa and Murray Silverstein) for architecture could be interpreted as an architectural version of the Hokusai Manga (and in fact Hokusai does include various architectural and landscape patterns which might possibly have acted as a hint).

EXCERPT ON CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER:

Alexander's writing reminds one of the manner of expostulation found in English language translations of Zen teachings and those of Daoism. As Harry Francis Mallgrave and David Goodman, some of the better known historians of architectural theory, write:

'The foundational piece of his trilogy is the The Timeless Way of Building (1979), which---with its Zen-like literary character and amorphous description of such elusive qualities as aliveness, wholeness, and beauty---indeed struck many at the time as an exercise in esotericism. When readers discovered that "timelessness" was an attribute found less in contemporary architectural creations and far more in older buildings and towns, it no doubt appeared to some as quaint or simple nostalgia. But the book has important empirical analysis as well as character, and in fact Alexander---a man who has devoted his life to discerning the "living patterns" of a successful architectural environment---has many thoughtful, if not profound, insights.' (An Introduction to Architectural Theory, 1968 to the Present, Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, p.86.)

His book starts with a few lines in the center of an otherwise blank page: "The Timeless Way: It is a process which brings order out of nothing but ourselves; it cannot be attained, but it will happen of its own accord, if we will only let it." ---sounding does it not, like Zen ideas about meditation and enlightenment, and of the workings of 'ki' (気).

Alexander's first examples are: "the Alhambra, some tiny gothic church, an old New England house, an alpine hill village, an ancient Zen temple, a seat by a mountain stream, a courtyard filled with blue and yellow tiles among the earth. What is it they have in common? The are beautiful, ordered, harmonious---yes, all these things. But especially, and what strikes to the heart, they live."

The idea of inanimate objects or structures as living, i.e., a wider conception of life, may be considered one of the key lessons for the West derived from Eastern philosophies---whether coming from Japan or China, and originating in India---which saw in the system of rebirth a wider conception of soulful creatures, and in the idea of all matter as part of an organic whole, the Atman self as Brahman, a conception of being that encompassed all matter, including of course the inanimate whether rocks, air, water, or buildings.

According to Alexander, "This one way of building has always existed. It is behind the building of traditional villages in Africa, and India, and Japan. It was behind the building of the great religious buildings: the mosques of Islam, the monasteries of the middle ages, and the temples of Japan." To realize the "timeless way" he speaks of "The Quality: To seek the timeless way we must first know the quality without a name." Again, echoes of Zen ideas concerning the shortcomings of verbal communication and argumentative expostulation as a means of attaining religious understanding and enlightenment. "There is a central quality which is the root criterion of life and spirit in a man, a town, a building, or a wilderness. This quality is objective and precise, but it cannot be named."

He continues in a vein analogous to Upanishadic or Buddhist sermonizing, in the repeating of opposites, in his reference to the illusion of dualities, the metaphysics of the objective vs. subjective, in his assertion of the ineffability of correct comprehension, and in his style of rhetorical questioning and statements: "We have been taught that there is no objective difference between gold buildings and bad, good towns and bad. The fact is that the difference between a good building and a bad building, between a good town and a bad town, is an objective matter. It is the difference between health and sickness, wholeness and dividedness, self-maintenance and self destruction. ... But it is easy to understand why people believe so firmly that there is no single, solid basis for the difference between good building and bad. It happens because the single central quality which makes the difference cannot be named."

As in Zen the self must be overcome and reach a state of 'ku' (空), so too Alexander states as to the quality without a name: "A word which goes much deeper than the word 'exact' is 'egoless.' When a place is lifeless or unreal, there is almost always a mastermind behind it. It is so filled with the will of its maker that there is no room for its own nature. Think, by contrast, of the decoration on an old bench--small hearts carved into it; simple holes, cut out while it was being put together---these can be egoless." As in Zen aesthetics, the mundane aspect of nature is without mind yet meaningful. Alexander then moves to the quality of "eternal", and as the first in depth example of his book he offers the following:

"I once saw a simple fish pond in a Japanese village which was perhaps eternal. A farmer made it for his farm. The pond was a simple rectangle, about 6 feet wide, and 8 feet long; opening off a little irrigation stream. At one end, a bush of flowers hung over the water. At the other end, under the water, was a circle of wood, its top perhaps 12 inches below the surface of the water. In the pond there were eight great ancient carp, each maybe 18 inches long, orange, gold, purple, and black: the oldest one had been there eighty years. The eight fish swam, slowly, slowly, in circles---often with in the wooden circle. The whole world was in that pond. Every day the farmer sat by it for a few minutes. I was there only one day and I sat by it all afternoon. Even now, I cannot think of it without tears. ..." (p. 38)

And Alexander continues as to its eternal nature. There are no further personal experiences or examples in this chapter. His next topic is "Being Alive" (Chapter 3). Here too, besides brief, fleeting images, it is another example from Japan that he dwells upon in any length:

"The great film, Ikiru---to live---describes it in the life on an old man. He has sat for thirty years behind a counter, preventing things from happening. And ten he finds out that he is to die of cancer of the stomach, in six months. He tries to live; he seeks enjoyment; it doesn't amount to much. And finally, against all obstacles he helps to make a park in a dirty slum of Tokyo. He has lost his fear, because he knows that he is going to die; he works and works and works, there is no stopping him, because he is no longer afraid of anyone, or anything. He has no longer anything to lose, and so in this short time he gains everything..." (font size changes, italics original, p. 49)

---it is Japan that has given Alexander his epiphanies and defining moments. He continues to speak of being alive in a fashion reminiscent of Ryokan san or other famous medicant monks as Saigyo, or a Daoist sage, and the poems they write, that it "has above all to do with the elements. The wind, the soft rain..." The one who is alive has "nothing to keep, nothing to lose. No possessions, no security, no concern about possessions, and no concern about security... Only the laughter and the rain." (p. 50-51)

END OF EXCERPT

EXCERPT ON JUHANI PALLASMAA:

Pallasmaa's aesthetics of tactility and multisensory experience share much in common with principles of Japanese residential architecture, such as outdoor-indoor unity and in the use of natural materials exposed and unpainted. There is an intimate connection between the specific architectural configuration, including the objects and actions that go with it, of a particular space, and the human body within it. The tea ceremony and the tea house is of course the quintessential example of this integration of the body and spatial configuration and interaction with the materials and non-visual sensory stimuli surrounding it, and Pallasmaa is well aware of that, writing:

"In The Book of Tea, Kakuzo Okakura gives a subtle description of the multisensory imagery evoked by the simple situation of the Japanese tea ceremony:

Quiet reigns with nothing to break the silence save the note of the boiling water in the iron kettle. The kettle sings well, for pieces of iron are so arranged in the bottom as to produce a peculiar melody in which one may hear the echoes of a cataract muffled by clouds, of a distant sea breaking among the rocks, or of the soughing of pines on some faraway hill.

In Okakura's description the present and the absent, the near and the distant, the sensed and the imagined fuse together. The body is not a mere physical entity; it is enriched by both memory and dream, past and future." (pp.48-49) While Pallasmaa follows with brief mention of a variety of philosophers and single line quotes from them, a concrete sense of what he wishes to convey---architecture as multisensory experience---and a poetic example of it, comes from living realities in Japan.

Pallasmaa follows with the importance of shadow, and with it tactile fantasy and the stimulation as well as soothing of the imagination. He writes: "Mist and twilight awaken the imagination by making visual images unclear and ambiguous; a Chinese painting of a foggy mountain landscape, or the raked sand garden of Ryoan-ji Zen Garden, give rise to an unfocused way of looking, evoking a trance-like, meditative state. The absent-minded gaze penetrates the surface of the physical image and focuses in infinity." (p. 50) Here again we see that often mention of other Asian cultures, most often the Chinese, are passing references without specificity, while in the case of Japan they come from personal experience, or at the very least a sense of empathetic feeling or vicarious experience from someone who has been there.

Pallasmaa continues with his reading of Tanizaki Junichiro's In Praise of Shadows, which really is what he has been talking about all along: In his book In Praise of Shadows, Jun'ichiro Tanizaki points out that even Japanese cooking depends upon shadows, and that it is inseparable from darkness: 'And when Y kan is served in a lacquer dish, it is as if the darkness of the room were melting on your tongue.' The writer reminds us that, in olden times, the blackened teeth of the geisha and her green-black lips as well as her white-painted face were all intended to emphasize the darkness and shadows of the room." (p.50) Perhaps not exactly what Tanizaki says, but the important point being that the idea of 'The Significance of the Shadow' as boldy, vividly, and cleverly annunciated in Tanizaki is what he is driving at, if one has read Tanizaki and compares it to Pallasmaa.

END OF 2ND EXCERPT

To be continued.

__________________________________

Initial upload 2023/9/16

Preview draft, text and captions to be added.

Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956)

Leading Architect of the Vienna Secession

The Japonisme of the Bold Right-Angle and Outline

Yasutaka Aoyama

"The boundless harm done to the applied arts on the one hand by poor mass production, and on the other by thoughtless imitation of old styles, pervades, like a giant current, the entire world. ... In place of the hand is most often a machine, in place of the craftsman the businessman appears. ... Nevertheless we have founded our workshop. It is intended to create a quiet place on our native soil... [A proclamation of affinity to the ideals of Ruskin and Morris follows, and a statement of ideas of value in the applied/fine arts, and then a commitment to pursuing the craftsman's joy of creation and an existence of dignity] ...What we want is what the Japanese have always done. Who could imagine any example of Japanese applied arts as manufactured?"

Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, 'The Program of Workmanship at the Wiener Werkstatte', Hohe Warte, 1904/05.

"Whether as a designer of the 'Ver Sacrum Room' for the first two exhibitions put on by the artists' association ... or as a designer of modern furniture and a graphic artist for 'Ver Sacrum', Josef Hoffmann had a formative influence on style. During this period it was evident both in his graphic works as well as in his architectural designs and furniture that Hoffmann owed a great deal to Japanese models: in the beginning the floral-linear style, then the deliberate reduction to the right-angled geometric forms and the use of the square as determining ornament were all developed by Hoffmann from his study of Japanese applied arts."

Rainald Frantz, Curator, MAK--Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, Japonisme in Vienna, 1994, p. 224.

If Otto Wagner's japonisme was of a subtle kind, applying a variety of Japanese motifs, blending structural elements into an elegant synthesis that could not be readily discerned as taking from Japan, those who followed him, such as Josef Hoffmann, brought selected aspects of Japanese design to the forefront of their designs with amplified emphasis. While adapting various designs found in Japanese pattern books and katagami, the aspect that Hoffmann focused upon, that would make his architecture distinctive, was the right angle geometric patterns and three dimensional geometric spatial designs in bold outlines pervasive in Japan. For while professing a kindred philosophical stance to William Morris' Arts and Crafts movement, in terms of the choice of concrete forms, Hoffmann looked to designs much more along the lines of Japanese applied arts and architecture.

Text to be added.

The omnipresence of 'right-angled geometric forms' in Japan

Text to be added.

Figures 1, 6, and 7 from Johannes Wieninger and Akiko Mabuchi (supervised), Japonisme in Vienna (exhibition catalogue), 1994.

The total surround of Japanese right-angled geometric environments

Text to be added.

Incorporating the smooth, clean, clear cut right-angle outlines of Japanese architectural design

Text to be added.

Facades based on bold, sharp and clean right-angle outlines/sections on a smooth, light surface in Meiji Japan

Text to be added.

Similar conceptions in different directions

Text to be added.

Hoffmann in context: the 'Ver Sacrum' and the aesthetic sources/origins of the Vienna Secession

We have chosen Josef Hoffmann as representative of what was a wide-spread phenomenon, without meaning to imply that Josef Maria Olbrich, for instance, an active contributor as graphic artist to Ver Sacrum, whose style, "whether in architecture or in his graphic works, is determined by echoes of the flowing floral-organic patterns of Japanese art" (Rainald Frantz, Olbrich biography in Japonisme in Vienna, 1994), or for that matter, painters such as Gustav Klimt, were any less interested in Japanese arts and crafts. Indeed, it can be argued that the influence of japonisme permeated into the work of virtually all the Secession artists---perhaps not so unlike how Greco-Roman art did so in Renaissance Europe four centuries earlier---a subject which we will come back to later.

But in particular, a new type of japonisme, of the right angle, the bold orthogonal outline, of simplicity and austerity, i.e. of the minimalism of residential Japanese architecture, was a phenomenon of some breadth, and can be seen in the design drawings of various architects at the time, and early on in the house of Belgian painter and designer Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921). As the German art historian Robert Schmutzler wrote in Art Nouveau (1962, 1977):

"In his own house, which he furnished entirely according to his own very unusual taste, there was an empty room with walls covered with Japanese brocade in which were set two bronze rings engraved with the names of Burne-Jones and Moreau [both representative of japonisme influences]. In the interior of this house, where no Art Nouveau curves are to be found, Japanese influences make themselves strongly felt in the simplicity and utter bareness of the rooms. Confined to the rectilinear and rectangular in every detail, the inside of the house is formed of box-like chambers, long corridors, and asymmetrically displaced passages. The same Japanese influence shows also in the lettering and typography created by Khnopff, who was a member of the Vingt, for the first catalogue of their exhibition of 1884." ( 1977 abridged version, p. 81)

Japonisme from the 1880's onward cannot be equated with any single source of Japanese art or any particular aspect of it. What characterized it was its multifaceted nature, which hungrily reached out in various directions in search for food for the imagination, continuing to consume the woodblock print (as in the example of the Ver Sacrum cover below), but also much more.

As in the case of Art Nouveau, from its very beginnings, the Jugendstil and Secession movement in Vienna was intimately tied to works of Japanese applied arts and crafts, rather than relying primarily on ukiyo-e prints as was the case for the earlier Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. The main voice of the Secession movement was the periodical Ver Sacrum, and regarding this publication, Rainald Frantz, curator at the MAK-Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, has written:

"The Japanese influence on the graphic art in 'Ver Sacrum' is latent in the magazine's style on the one hand through the inspirational effect of East Asian book production and woodcut art, and on the other through the technique of silk screen printing on textiles. The Viennese designers encountered in the Japanese idiom an art which matched their aims by favouring to a large degree the abstraction of a prototype image taken from nature by creating a formal interpretation of it. The most obvious example of the Japanese influence can be seen in the ninth issue of its second year in 1899: there was a direct reference to a Japanese colour woodcut in the jacket design of this issue, which appeared at the same time as the VI Secession exhibition of Japanese art from the collection of Adolf Fischer already planned for that year. The magazine presented examples of Japanese stencil cutting in black and white, which consequently acted again as models for planar pattern designs by the Secession artists who contributed to 'Ver Sacrum.' "