Literary Japonisme

文学のジャポニスム論

Photo: Detail of bronze statue of King Rama III, holding a Japanese sword, Royal Pavilion Mahajetsadabadin, Bangkok, Thailand. In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Japanese samurai such as Yamada Nagamasa worked as military commanders and soldiers for Thai monarchs. Later, the success of the Meiji Restoration made a deep impression upon political leaders and thinkers not only throughout Southeast Asia, but also westward to India and the Ottoman Empire, south eventually to Ethiopia, and eastward to the Kingdom of Hawaii.

Uploaded 2025.2.11

Under construction

On Emily Dickinson

Starting with an Excerpt from

The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics, and the Opening of Old Japan

(New York: Random House, 2004, pages 210-211)

by Christopher Benfey

Mellon Professor of English at Mount Holyoke, 'well-known scholar of Emily Dickinson'

His numerous writings include: Emily Dickinson and the Problem of Others (1984), A Summer of Hummingbirds: Love, Art, and Scandal in the Intersecting Worlds of Emily Dickinson, Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Martin Johnson Heade (2008),

The Double Life of Stephen Crane (1992 ), and Degas in New Orleans (1997).

Was there something Japanese about Emily Dickinson? Mabel Todd thought so, as she painted, with brush and ink, a Dickinson poem for the people of Hokkaido. Amy Lowell seems to have thought so, too, as she turned from her imagery of the "floating world" to the haiku-like nature poetry of the Belle of Amherst. Ernest Fenollosa thought so, when he drafted a talk on Chinese and Japanese peotry in New Orleans, on December 22, 1896, just as the Todds were rounding the Horn on their long way back to Amherst. Fenollosa was trying to identify a property common to all poetical thought. "The harmony of poetic thought and word must be married," he concluded. "Each is a potent magic fluid, completely solvent of the other. Oriental poetry is specially deep in this field. Its highest philosophy was to read soul in nature. ... There excellence of oriental is very high. Pure emotion. Generally very brief---In this resemble modern tendencies/Emily Dickinson."

The Fenollosas shared their enthusiasm for Dickinson with others in their circle. On April 7, 1898, during their sojourn in Kyoto, Mary wrote in her journal, "We got our Emily Dickinson from Okakura, but not other books." This would make Okakura the first documented Japanese reader of Dickinson. A few years later, in his "Notes for a Lecture on Chinese poetry" of 1902, Fenollosa again thought of Dickinson in relation to what he called the "condensation and brevity" of the Chinese poetic language: "Like modern English/like our Emily Dickinson/like Emerson/Long poem impure---like long music/impression---."

As Akiko Murakata has noted, Fenollosa "did not live to see the full blossoming of Imagism nor the publication of his lecture at Columbia University in 1901, 'The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry,' " which Ezra Pound edited and published in The Little Review in 1918. This slim volume, in which Fenollosa argued that the Chinese ideogram retained a pictorial and metaphorical force lost to European phonetic languages, had an enormous influence on twentieth-century American poets.

Not that emily Dickinson hereself showed any particular interest in Japan. Though there are scattered reference to Asia in her poems and letters, she seems to have mentioned Japan only once. "That you glance at Japan as you breakfast, not in the least surprises me, thronged only with Music, like the Decks of Birds." So she wrote to her childhood friend the novelist Helen Hunt Jackson (who was living in California) in the early spring of 1885. And yet there does seem to be something Japanese in Emily Dickinson's whole stance---something that, by the way, has appealed to generations of Japanese readers and scholars, many of whom make the pigrimage each year to the big brick house on Main Street in Amherst in which Dickinson was born and died.

With her short, intensely observed poems of natural occurrences, Dickinson resembles thos hermit-poets of China and Japan who found in the splash of a frog some clue to the workings of the universe. The change of the seasons---"These are the days when birds come back," "A light exists in Spring," "Further in summer than the birds"---is crucial to Dickinson and crucial to Basho and the classic haiku poets. Emily Dickinson's love for a few conventional stanza shapes also seems somehow Japanese, as does her reticence, her zealously guarded privacy, her love of solitude and silence. Like an epigraph from The Tale of Genji, her imperious lines impose a spiritual boundary:

The soul selects her own Society,

Then shuts the door.

Uploaded 2023/4/19

Under construction

Japan in the British Imagination

Bacon, Stalker, Swift, & Smollett

Utopian and Make-believe Worlds of the 17th and 18th Centuries

Yasutaka Aoyama, PhD

EXCERPT:

Japan in Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis

The idea of Japan as a model for utopia, in the late Victorian and Edwardian British imagination, has been discussed in ‘Bushido Japonisme’ (Aoyama, 2021), centered upon H. G. Wells’ leadership class called the “Samurai” in his novel A Modern Utopia. But Japan as a stimulus for utopian imaginings may go back much further—perhaps by three centuries, to one of England’s most famous philosophers, Francis Bacon. His opening line of one of the very first utopia novels, New Atlantis (1627) is:

“We sailed from Peru, (where we had continued for the space of one whole year) for China and Japan, by the South Sea; taking with us victuals for twelve months; and had good winds from the east, though soft and weak, for five months space, and more.”

The original destination of Bacon’s imaginary voyagers then, is the Far East, China and Japan, like it was, by the way, for the real voyage of Christopher Columbus. Like Columbus however, Bacon’s voyagers do not arrive at their intended destination:

“But the wind came about, and settled in the west for many days, so as we could make little or no way, and were sometime in purpose to turn back. But then again there arose strong and great winds from the south, with a point east, which carried us up (for all that we could do) towards the north; by which time our victuals failed us, though we had made good spare of them.”

It is here that the New Atlantis lies, which is the stage for Bacon’s ideal society, but not much has been done in the way of tracing any specific sources for Bacon’s description of this journey, however, since D. W. Thompson, in his article ‘Japan and the New Atlantis’ (Studies in Philology, 1933), argued that Bacon’s voyage descriptions resemble those of the Englishman William Adams, a historical figure who lived and died in Japan and wrote about his travels there in the early years of the 17th century, and who, by the way, was latter to be the model of the central character of James Clavell’s novel Shogun (1975). British merchant travelers to Japan, such as Richard Cocks and John Saris, who established a trading factory in Kyushu, were reporting on Japan and bringing Japanese artifacts to England in the decades just before Bacon's publication of New Atlantis...

END OF EXCERPT

2ND EXCERPT:

...It may at first seem that China, if anything, should be of more concern in discussing New Atlantis than Japan, since there is good bit of mention of China. But it is all in the negative, that is China is brought into the picture to contrast it with Atlantis---reminiscent of Jesuit descriptions in the late 16th and 17th century, and of later English descriptions contrasting Japan with China. Japan is oddly absent in New Atlantis, despite being the ultimate destination of Bacon's travellers along with China. Indeed, after the first line of the book, Japan is thereafter never mentioned, while the Americas (such as Peru and Mexico), China, Egypt, Phoenicia, Carthage, Africa, Persia, and Israel, for instance, are. The Atlanteans sometimes, as in burial, do as the "Chineses do their porcellain"; ---for some reason, China is a repeated point of comparison with Atlantis, as in the case of European commentary on Japan.

Bacon's version of Atlantis may contain elements of travelogues to other countries as well, but if we look at the initial encounters with the representatives of Atlantis, their speaking Spanish, their questionings on religion; their boarding and demands; the chief emissary's "gown with wide sleeves, of a kind of water chamolet" (wavy water pattern); how the English "bowed themselves toward" the Atlantean emissary at sea; or are later taken to a "Strangers' House" with a diverse array of different foods and wines; then there are medicines of "long fermentations"; an eye-opening, sensory-rich world of music and theatrics; "fair and large baths"; "artificial wells and fountains" rich in minerals good for health and "prolongation of life" reminiscent of Japan's abundant hot springs and baths; and "fireworks of all variety"; and so many other various other points of detail, anyone familiar with the accounts of travelers to Japan in the late 16th and early 17th centuries cannot help but suspect some connection with that country.

Even in the lay of the land, Atlantis echoes of Japan; a land of "magnificent temple, palace, city, and hill; and the manifold streams of goodly navigable rivers, (which, as so many chains, environed the same site and temple)"; a "rare fertility of the soil in the greatest part thereof;" where the ruler understood the "shipping of this country might be plentifully set on work, both by fishing and by transportations from port to port"; and furthermore, there exist:

"small islands that are not far from us, and are under the crown and laws of this state"

---that is, a geographical, architectural, political, and economic conceptualization, which is again, not at odds with the Japan of the time. Furthermore, as in Japan, foreign access and egress by the local population is regulated, in what would develop into the 'sakoku' or the 'closed door' policy; and once again Bacon contrasts the Japanese version of this type of policy with that of China, as if it were a natural turn of discourse regarding Atlantis:

"It is true, the like law against the admission of strangers without license is an ancient law in the kingdom of China, and yet continued in use. But there it is a poor thing; and hath made them a curious, ignorant, fearful, foolish nation. But our lawgiver made his law of another temper. For first, he hath preserved all points of humanity, in taking order and making provision for the relief of strangers distressed; whereof you have tasted." At which speech (as reason was) we all rose up, and bowed ourselves. He went on. "That king also, still desiring to join humanity and policy together; and thinking it against humanity to detain strangers here against their wills, and against policy that they should return and discover their knowledge of this estate, he took this course: he did ordain that of the strangers that should be permitted to land, as many (at all times) might depart as would; but as many as would stay should have very good conditions and means to live from the state."

This of course sounds very much like the policy of Nobunaga and Hideyoshi, who were frequently conversing with the Jesuits, and especially the Tokugawa Shogun Ieyasu, who allowed the English Factory at Hirado and retained William Adams as his advisor, giving him high rank and wealth, in contrast to the situation in China, where the Jesuits and English were not allowed to proselytize or conduct commerce freely until much later. Furthermore, just as Chinese merchants frequently came to Japan, but the Japanese were less encouraged to frequent abroad, so the policy of the Atlantis 'Lawgiver':

"Now for our travelling from hence into parts abroad, our Lawgiver thought fit altogether to restrain it. So is it not in China. For the Chineses sail where they will or can; which sheweth that their law of keeping out strangers is a law of pusillanimity and fear. But this restraint of ours hath one only exception, which is admirable; preserving the good which cometh by communicating with strangers, and avoiding the hurt..." (Bacon in Random House ed. 1955, p. 562)

Once again, the experience of the English voyagers in Atlantis recalls that of William Adams. According to him, the Japanese are valiant, civil, sensible and governed by the rule of law:

"The people of the Island of Japon are good of nature, courteous above measure, and valiant in warre" and their "iustice is severely executed without any partialite upon transgressors of the law. They are governed in great civilities. I meane, not a land better governed by civil policie." (In Foster Rhea Dulles, Eastward Ho! The first English Adventurers to the Orient, 1931/69, p.123)

Compare this with Bacon, whose travelers during their stay at Atlantis:

"...lived most joyfully, going abroad and seeing what was to be seen in the city and place adjacent within our tedder [i.e., tether, or the circumscribed limit of a mile and a half] and obtaining acquaintance with many of the city, not of the meanest quality; at whose hands we found such humanity, and such a freedom and desire to take strangers as it were into their bosom, as was enough to make us forget all that was dear to us in our own countries"---what also might be said of William Adams with respect to Japan--- "and continually we met with many things right worthy of observation and relation; as indeed, if there be a mirror in the world worthy to hold men's eyes, it is that country." (Bacon in Random House ed. 1955, p. 564-565)

END OF 2ND EXCERPT

3RD EXCERPT

Sir Thomas Wilson, member of the Cecil and Walsingham circle, described Richard Cock's reports to King James I in March of 1619, telling the king (parentheses added):

"It seemes that neather our cosmographers nor other wryters have given us true relation of the greatnes of the princes of those parts, for...of the island of Japan hee tells these strange things following. Warrs wherin 300 thousand men slayne at a tyme. A king's courte of an 100 thowsand men continually resident. A king's pallace capable to lodge 200 thousand men, far bigger then your Majestie's citty of York. The citty without 3 tymes as much more. Temples & colossoes of admirable consideration, in this our Christian world greater then that of Rhodes (the legendary Colossus of Rhodes, Greece), which is one of the world's wonders. Many other wonders, but rudely described by a marchant's style."

After so giving Cocks' description of Japan to King James, Wilson noted:

"His Majesty redd (read) & discorced (discoursed) with me about them, but cold (could) not be induced to beleeve that the things written are true, but desyred to speake with the writer when he comes home."

END OF 3RD EXCERPT

One of the two suits of Japanese armor brought back to England by John Saris for King James I in 1613. Tower of London collection. Photo: Wikicommons.

EXCERPT:

Japan in John Stalker’s A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing

Just as ‘china’ referred to, and still refers to, fine porcelainーand for good reason, ‘japan’ and ‘japanning’ once referred to fine lacquer and lacquering for equally good reasonーuntil the coming of the Second World War. The fate of the word ‘japanning’ is an apt symbol for the fate of the marvelous history of 'japonisme' itself, banished to oblivion. We must never assume our present world views, based not upon primary historical sources but on generalized conceptions established in the mid-20th century, reflect in any way the actual attitudes of cultivated minds in past centuries. In A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing (1688) by John Stalker, published half a century after Bacon’s New Atlantis, Japan exceeds both the Renaissance Vatican and the Pantheon of classical Rome in glory.

“Ancient and modern Rome must now give place:

The glory of one Country, Japan alone, has exceeded in beauty and magnificence all the pride of the Vatican at this time,

and the Pantheon heretofore...”

Stalker’s book contains a utopian vision that would be echoed more than two centuries later in H.G. Wells’ A Modern Utopia, which speaks of a general brightness of the air that characterizes the utopian environment. And Stalker in turn, was in fact echoing Marco Polo, when writing that Japan:

“was overlaid with pure Gold, and 'twas but proper and uniform to cloath the Gods and their Temples with the fame metal. Is this so strange and remarkable? Japan can please you with a more noble prospect, not only whole Towns, but Cities too are there adorned with as rich a Covering; so bright and radiant are their Buildings, that when the Sun darts forth his lustre upon their Golden roofs, they enjoy a double day by the reflection of his beams.”

In other words, as he summarizes in the concluding lines of his preface, so brilliant in gold is this “favorite (abode) of the gods” that the air is doubly bright, a place where Midas’ wish comes true...

END OF EXCERPT

Illustration for A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing by John Stalker. Photo: Public domain, MET

EXCERPT:

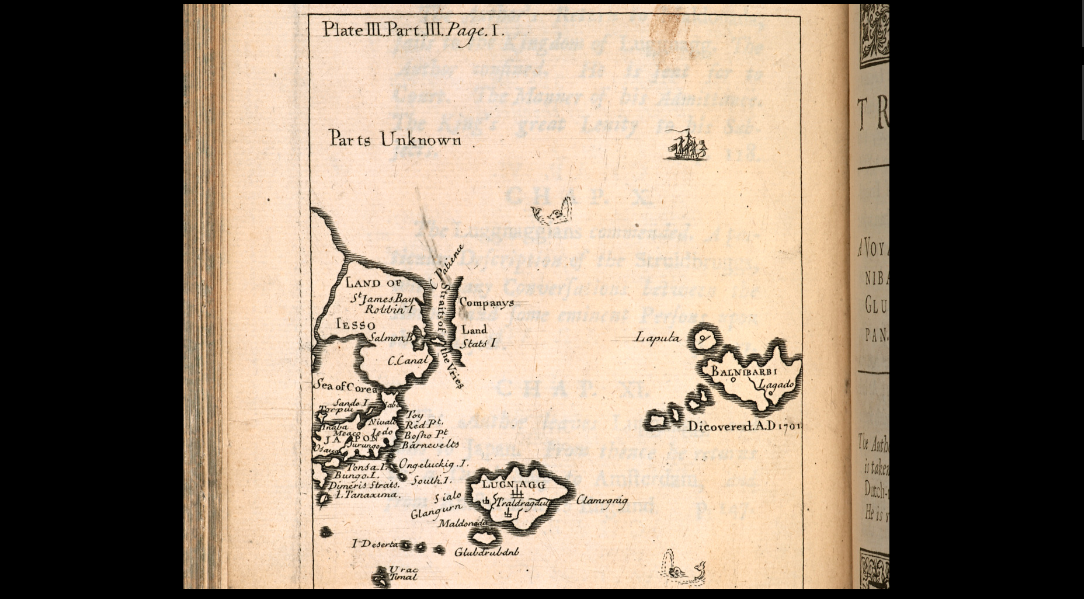

Japan in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels

Approximately half century after Stalker, one of England’s first novelists, Jonathan Swift, has his character Gulliver head for Japan in his voyages to the further reaches of the world. What is interesting here is that Japan is the only land in the novel which is a real country; the rest are all concoctions, with fantastically strange sounding names emphasizing a sense of complete alienness to Europe. The exact title of Part III of Gulliver’s Travels (1726) is:

“A VOYAGE TO LAPUTA, BALNIBARBI, LUGGNAGG, GLUBBDUBDRIB, AND JAPAN.”

It might be inferred from this that Japan was considered on par with the rest in terms of conveying exoticism, to be included as is, or perhaps, considered so exceedingly exotic at the time as to enhance the exoticism of other make-believe lands by mental association, as a fitting cap to a list of fantastical names.

The Dutch, who were considered to be England’s archenemy in the latter 17th and early 18th centuries, are portrayed contrastingly to the Japanese, who are fearsome but also merciful. Gulliver is willing to bow deeply to the Japanese, in part to save his life, but not with distaste nor hesitation:

“The largest of the two pirate ships was commanded by a Japanese captain, who spoke a little Dutch, but very imperfectly. He came up to me, and after several questions, which I answered in great humility, he said, “we should not die.” I made the captain a very low bow, and then, turning to the Dutchman, said, "I was sorry to find more mercy in a heathen, than in a brother christian."

Gulliver thus speaks in an admonitory tone to this fellow European, only to find himself viciously maligned by the same; while the Japanese captain shows himself to be a more noble character, generous as far as might be allowed in the circumstances, and firm in his (though limited) merciful intentions:

“But I had soon reason to repent those foolish words: for that malicious reprobate, having often endeavoured in vain to persuade both the captains that I might be thrown into the sea (which they would not yield to, after the promise made me that I should not die), however, prevailed so far, as to have a punishment inflicted on me, worse, in all human appearance, than death itself. My men were sent by an equal division into both the pirate ships, and my sloop new manned. As to myself, it was determined that I should be set adrift in a small canoe, with paddles and a sail, and four days' provisions; which last, the Japanese captain was so kind to double out of his own stores, and would permit no man to search me. I got down into the canoe, while the Dutchman, standing upon the deck, loaded me with all the curses and injurious terms his language could afford.”

It may be gleaned here that Swift too, is going along with the highly favorable opinions of Japanese character in Europe based on a a growing body of literature on Japan, building upon the glowing commentaries of Jesuit missionaries in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. In fact, Swift, besides his section on Japan in Gulliver’s Travels, wrote more about the country in his An Account of the Court and Empire of Japan, Written in MDCCXXVIII (1728), as discussion of the Far East was becoming something of a vogue in Europe...

END OF EXCERPT

2ND EXCERPT FOR SWIFT:

...and regarding this amazing correspondence between Kaempfer's diagram and Swift's plate it is perhaps best to allow these three scholars to speak for themselves, whose argument this author (also familiar with Japanese) finds convincing:

"... Over 250 years ago, in words that seem more suitable for our cybernetic age, Jonathan Swift introduced the world to a prototype computer in the middle of Part III of Gulliver's Travels. The Projector Professor of 'the grand Academy of Lagado' had programmed a machine into which he 'emptyed the whole Vocabulary... and made the strictest Computation of the general Proportion there is in Books between the Numbers of Particles, Nouns, and Verbs, and other Parts of Speech.' ..."

"It is, moreover, immensely significant that to a trained eye, the characters in the earliest plate (quite distorted in later issues and editions)---256 characters in all---show striking resemblances to the ancient Japanese syllabaries which, as we shall demonstrate, were available to Swift in the travel literature he is known to have read and often parodied in his masterpiece. ..."

"The symbols in the Gulliver 'Figure' show an almost complete correlation with those of the Japanese syllabaries as Kaempfer printed them. Like the parts of the Projector’s Contrivance, the language signs in Japanese are not genuine 'alphabet elements’ but syllable forms numbering in the hundreds and thus comprising a word stock for writing. There are three styles of Japanese Kana syllabaries: the Hiragana and Katakana which are still used very much as Kaempfer reproduced them and which seem to dominate Swift’s system, and the more complicated Hentaigana which dropped from usage about a century ago (these are seldom seen in the Gulliver plate). By close comparison and the compilation of parallels, we find evidence suggesting that Swift and/or the designer of his plate drew directly from a table of the Japanese language as given in Kaempfer's History." (Johnson, et al. 1977)

The distortions in later editions mentioned above are quite odd and pronounced (in comparison with the maps which are replicated close to their original form); and when closely examined, they are most logically construed as deliberate alterations in later ages, perhaps when recognizably clear associations with the Japanese language would no longer be pleasing to either the literati elite or the common reading public. ...

END OF 2ND EXCERPT

3RD EXCERPT

But the fact is that the Far East---China and Japan---were on the minds of the English reading public in the late 1720's, just when Swift was writing his book. The deistic 'heresy', with its origins in continental Europe, colored with justifications using Chinese as well as other faraway exotic examples, provoked a Church response by Edmund Gibson, then presiding bishop of London. In his 1727 The Bishop of London's First Pastoral Letter to the People of his Diocese: Occasioned by some late Writings in Favor of Infidelity, he condemned the belief in the 'noble savage' and 'noble sage' as to their natural goodness, and elsewhere in the notes referred to practices in China, Japan, Formosa, Ceylon, and India (Christy, 1945). Rebuttals followed, among which was that of Matthew Tindal, "archdeist of his time" who paired Britain with Japan for greater rhetorical persuasion in his 1728 Address to the Inhabi[t]ants of the two great Cities of London and Westminster In Relation to a Pastoral Letter: "If Men in Great-Britain no more than Japan, ought to owe their Religion to the Chance of Education; but are equally obliged to examine what may be said on all Sides, One would have thought, that a Protestant recommending Sincerity in the Choice of Religion, should not have used such Arguments..." (London: Printed and Sold by J. Peele, pp. 35-36).

END OF 3RD EXCERPT

Plate III, Part III, Page 1, from the original edition of Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels. Note Japan (Japon) to the left with Hokkaido (Iesso, i.e., Ezo) shown above as a large land mass.

Doshisha University study group (Johnson, et. al.) comparison of Gulliver's (top) script in his table versus Japanese script in Kaempfer's table.

EXCERPT:

Japan as Another Self in Tobias Smollett’s Critical Review (1759) and The History and Adventures of an Atom (1769)

Moving forward a quarter of a century or more from the age of Swift, with the coming of the industrial revolution and overseas empire, and the changes they wrought to English society, Britain’s sense of identity, and with it its perceptions of foreign nations, including those of Japan, naturally underwent transformation. From a paradisiacal/fantastic Japan, beyond common comprehension, comes next the idea of a Japan similar to Britain, Japan as a sort of mirror image or alternate self; an idea expressed, for example, in the writings of one of the key literary figures of the day, Tobias Smollett. As editor of the Critical Review, in his comments on ‘Art. II. The Modern Part of an Universal History', he wrote:

“The ninth volume opens with the history of Japan, a subject equally curious and important: important with respect to the power, wealth, and commerce of that empire; and curious, whether we consider the genius and acquired knowledge of the people, or the nature of their situation, which is, in many respects, analogous to that of Great Britain.” (September 1759, pp. 189-196)

Already Europe has had almost two centuries of increasing contact with Japan, and gone is the idea of a wonderland covered in gold; instead is a conception, though still very positive, tinged with more realism and detail:

“Japan, though considerable in riches, arts, and strength, is but small in point of extent. It consists of three larger, and divers smaller islands, on the most eastern verge of Asia; and the whole may be about six hundred leagues in compass.”

And elsewhere:

“The author having given the natural history of the country and the people, including their religion, laws, government, kings, priests, nobles, court, commonalty, standing forces, revenue, palaces, towns, learning, customs, trade and manufacture, traffick with the Dutch, manner of living, diet, diversions, festivals, banquets, burials, proceeds to delineate the division and topography of the country. In this section we find a description of the principal cities in Japan, called Meaco (Miyako), Jeddo (Edo), Osacca (Osaka), Gurunga (Tsuruga?), and Saccai (Sakai).” (From page 193, parenthesis are this author’s annotations)

A more detailed analogy to his own country is outlined. Japan is brought down from its awe-inspiring, utopian heights to the realistic level of Britain, and becomes a place that can be considered familiar and readily comprehended:

“Our author justly observes, that if England and Scotland were divided from each other by an arm of the sea, Japan might be aptly compared to Britain and Ireland, with all their capes, bays, channels, peninsulas, and islands, subjected to the dominion of one monarch. He might have pursued the comparison in divers other particulars. The coasts of Japan are dangerous and rocky; so are those of Great Britain. The climate of Japan is wet, stormy, and variable; so is that of Great Britain. Both countries produce great quantities of corn for exportation, as well as for home consumption: they are both famous for their sheep, oxen, and mettled sleet horses; and their seas abound with variety of fish, The hills of Japan are stored with metals and minerals; so are those of Great Britain: here, however, there is an essential difference, Japan yields gold in the mine, but Britain turns its metals into gold."

Smollett thus hints that while Japan is like Britain, Britain is superior, for while Japan has been much touted for having much gold by good fortune, British genius turns baser metals into gold. Otherwise, the two nations are similar, not only in terms of geography and economy, but in terms of national character:

“There is, moreover, are semblance in the genius and disposition of the people: the Japanese, like the English, are brave and warlike, quick in apprehension, solid in understanding, modest, patient, courteous, docile, industrious, studious, just in their dealings, and sincere in their professions. ... Perhaps the analogy is still more remarkable between Japan and Britain, if we consider them both as they are situated with respect to their neighbours. The next continent to Japan is China, which, in divers respects, may be compared to France, that lies nearest to Great Britain. China is more populous, powerful, and extensive, than Japan, which it boasts of having originally settled: its palaces are more grand; its court is more magnificent; its armies are more numerous, and its police is better regulated. It is the elder in literary, as well as in mechanical arts, the centre of taste, and source of fashion."

Thus ideas about China and Japan are also a reflection of British perceptions of their own cultural relations with the European continent, and it is amazing how the basic stereotypes of China and Japan, formed centuries ago, remain unchanged to this day:

"But what the Chinese invented, the Japanese have improved:

the former have discovered arts which the latter have brought to perfection."

END OF EXCERPT

Pages from Tobias Smollett's The History and Adventures of an Atom, 1769.

Bibliography (Partial)

Bacon, Francis. Advancement of Learning; Novum Organum; New Atlantis. (1627) Chicago: William Benton / Encyclopedia Britannica, 1952.

______________. Selected Writings of Francis Bacon, with an introduction and notes by Hugh G. Dick, Professor of English, University of California at Los Angeles. New York: Random House, 1955.

______________. Advancement of Learning, The New Atlantis, with a Preface by Thomas Case. London: Henry Frowde, Oxford University Press, 1906.

Bodart-Bailey, Beatrice M. ‘Gulliver’s Travels, Japan and Engelbert Kaempfer’. Otsuma Journal of Comparative Culture, volume 22, 2021-03-01, pp. 75-100. Tokyo: Otsuma University, department of comparative literature (大妻女子大学比較文化学部).

Caron, François. A true description of the mighty kingdoms of Japan and Siam. Written originally in Dutch by Francis Caron and Joost Schooten: and now rendred into English by Capt. Roger Manley. London: Printed by Samuel Broun and John de l'Ecluse, 1663.

Conant, Martha P. The Oriental Tale in England in the XVIII Century. New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1908.

Cooper, Michael (ed.). They Came to Japan: An Anthology of European Reports on Japan, 1543-1640. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1965.

Christy, Arthur E. (ed.) The Asian Legacy and American Life. New York: The John Day Company, 1942, 1943, 1945.

Cullen, L.M. ‘Gulliver in Japan’. Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an dá chultúr, Vol. 28 (2013), pp. 170-176. Published by the Eighteenth- Century Ireland Society. At https://www.jstor.org.

Delboe, Simon; Gibben, Hamond; Ramsden, William. 'The Second Appendix to Dr. Engelbert Kaempfer's History of Japan, Being Part of an Authentick Journal of a Voyage to Japan, Made by the English in the Year 1673.' J.G. Scheuchzer, editor. London: Printed for Thomas Woodward and Charles Davis, 1728.

Eddy, William Alfred. Gulliver's Travels, A Critical Study. New York: Russell & Russell, 1963, reprint of Princeton University Press, 1923. Online at https://archive.org.

Fucan, Fabian. Feiqe monogatari. Published by the Jesuit mission in Japan, 1592.

Goldsmith, Oliver. The Citizen of the World: or Letters from a Chinese philosopher, Residing in London, to his Friends in the East. Dublin: Printed for George and Alex. Ewing, 1762.

Hatch, Arthur. Letter to Samuel Purchas, dated November 25, 1623, from Wingham, Kent. English preacher aboard the Palsgrave, who reached Hirado in 1620. Contains a detailed description of Japan. Discussed in Cooper 1965.

The Japan Foundation Information Center Library. 'Engelbert Kaempfer, The History of Japan, London, 1727-1728'. Online at https://www.jpf.go.jp

Johnson, Maurice; Kitagaki, Muneharu; Williams, Philip. ‘Japan‘s Contributions to Gulliver's Travels.’ Kyoto: Amherst House, Doshisha University, 1977. Online at https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp.

_____________________________________________________. Gulliver's Travels and Japan: A New Reading. Kyoto: Amherst House, Doshisha University, 1977.

Jorissen, Engelbert. 'Exotic and "Strange" Images of Japan in European Texts of the Early 17th Century: An Interpretation of their Contexts of History of Thought and Literature.' Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies, June 2002, No. 4, pp. 37 - 61. Lisboa: Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

Kaempfer, Engelbert. The History of Japan, Together With a Description of the Kingdom of Siam, 1690-92. 2 volumes. London: Printed for the translator J. G. Scheuchzer, 1727. After Kaempfer’s death in 1716, his manuscript for The History of Japan was acquired by the renown collector Sir Hans Sloane and translated into English by his librarian, a Swiss doctor named Johann Caspar (Gaspar) Scheuchzer, who published it 1727. Thus the manuscript was in the hands of a leading member of Irish-English society (who served as Royal Physician and President of the Royal Society, showing items in his vast collections not only to domestic audiences but to the likes of Voltaire, Benjamin Franklin, and Carl Linnaeus) before Swift's publication of Gulliver's Travels. Despite some vehement arguments against it, a possible viewing by Swift as discussed by scholars such as Maurice Johnson, et al. cannot be completely precluded. Even if Swift did not see Kaempfer's work, that does not mean he had not incorporated knowledge from what he read or heard about Japan, as there were a number of lengthy sources already available on the country, such as Purchas and Varenius' descriptions of Japan published in the early and mid-17th century.

Korniscki, P. F. 'European Japanology at the End of the Seventeenth Century'. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London Vol. 56, No. 3 (1993) pp. 502-524. Cambridge University Press.

Maverick, L. A. 'The Chinese and the Physiocrats: A Supplement'. Economic History, Vol. 4, No. 15 (Feb. 1940), pp. 312-318. London: Royal Economic Society.

Minakawa, Saburo. Diary of Richard Cocks (1615). Tokyo: Gakuseisha, 1953.

Montanus Arnoldus. Atlas Japannensis: being remarkable addresses by way of embassy from the East India Company of the United Provinces, to the emperor of Japan. Containing a description of their several territories, cities, temples, and fortresses. London: Printed by Tho. Johnson, 1670.

Moxon, Joseph. A brief discourse of a passage by the North-Pole to Japan, China, &c. Pleaded by three experiments: and answers to all objections that can be urged against a passage that way...with a map of all the discovered lands neerest to the pole. London: Printed for Joseph Moxon, and sold at his shop, 1674.

Nerebegood, Sir Tristan (pseudonym). Man unmask'd: being a wonderful discovery lately made in the island of Japan: written in the Japonese language by the spirit of contradiction, and translated into English for the Benefit of the Publick, by Sir Tristan Nerebegood. London : Printed for J. Nutt, near Stationers-Hall, 1706.

Oba, Haruka; Watanabe, Akihiko; Schaffenrath, Florian. Japan on the Jesuit Stage: Transmissions, Receptions, and Regional Contexts. Jesuit Studies Volume: 34. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2022.

Psalmanaazaar, George.An Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa, an Island Subject to the Emperor of Japan. (1704) N. M. Penzer, ed. London: Robert Holden, 1926.

Purchas, Samuel. Purchas his Pilgrimes, in Five Bookes. London: Printed by William Stansby for Henrie Fetherstone, 1625.

Reisner, Thomas A. 'A new source for Goldsmith's 'Citizen of the World'. Notes and Queries Vol. 40, Issue 3 (Sept. 1993) pp. 334-5. Oxford University Press.

Satow, Ernest Mason. The Voyage of of Captain John Saris to Japan, 1613. London: Hakluyt Society, 1900. Online at University of Oregon e-Asia Digital Library.

Shimada, Takau (ed.). Japan in Eighteenth-Century English Satirical Writings. Tokyo: Edition Synapse, 2007.

_______________. ‘Possible Sources for "Gulliver's Travels"’. Philological Quarterly, Volume 63, No. 1 (Winter 1984), p. 125. Iowa City: Univ. of Iowa.

Smollett, Tobias (ed.). Critical Review, September 1759, pp. 189-196. London.

_________________. The History and Adventures of an Atom. In Two Volumes. London: Robinson and Roberts, MDCCLXIX (1769).

Stalker, John and Parker, George. A Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing: Being a compleat Discovery of those Arts. London and Oxford: Printed for and sold by the authors, 1688.

Swift, Jonathan. An Account of the Court and Empire of Japan. Written in MDCCXXVIII (1728). In The works of Dr. Jonathan Swift, Dean of St. Patrick’s, Dublin. Volume viii, Part I. Collected and revised by Deane Swift, Esq; of Goodrich, in Herefordshire. Viii 101-110. London: William Johnston, 1765. (Oxford Text Archive).

______________. Travel into Several Remote Nations of the World. In four parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, first a surgeon, and then a captain of several ships. (Gulliver's Travels) London: Printed for Benj. Motte, 1726. Partially online at https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/first-edition-of-gullivers-travels-1726.

Thompson, D. W. ‘Japan and the "New Atlantis". Studies in Philology, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Jan. 1933), pp. 59-68. Chapel Hill, NC: Univ. of North Carolina Press. At https://www.jstor.org.

Varenius, Bernard. Descriptio Regni Iaponae Cum quibusdam affinis materiae... Amsterdam: Ludovicum Elzevirium, 1649. Online at Google Books.

Sir Thomas Wilson to James I, London, March 1619. Public Record Office (UK): SP 14/96.

************

Uploaded 2023.3.27

(Adaptation for online publication of a 2021.1.27 exhibit commentary )

James Michener’s Hokusai Sketchbooks

&

The Japonisme Renaissance (1955-1985)

Yasutaka Aoyama, PhD

Besides his popular family sagas, James Michener authored several books on Japanese prints, among which The Hokusai Sketchbooks (1958), a commentary and eulogy of the ukiyo-e master Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), was perhaps the work related to Japan most dear to the writer himself. Michener's love of Hokusai's manga is representative of the general resurgence in America, from the 1950’s onward, of favorable interest in Japanese arts and culture, shared by many of Michener's fellow writers during the latter half of the 20th century. From ‘Beat’ generation poets like Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Gary Snyder, to novelists as different as Richard Wright, Henry Miller, and William Faulkner (not to mention artists, composers, and movie-makers), Japan was at the very least a place of aesthetic discovery, and more often a meaningful source of spiritual and creative inspiration. For others it was a useful literary device—for James Clavell an ancient and magnificent social setting; or for Kurt Vonnegut a symbol of a disturbed and dystopian future. Whatever the case, viewed in historical perspective, one might rightly call the 30 years from the mid-1950’s to the early 1980’s a grand revival of japonisme, mainly among artists and intellectuals, but also to a good extent among the business community and even the general public, lasting well up to the eve of the US-Japan trade related disputes in the 1980’s.

Addendum:

The term 'Japonisme Renaissance' is meant to reflect a revival in the broadest sense of the term, much like the Italian Renaissance of Greco-Roman culture in all its forms. Here we have focused on literature, but we could of taken almost any of the other arts as an example. Japan also had an impact on philosophy and academic scholarship as well, and of course technology; ---and even pure science. Perhaps Japan was of special interest because of the many specific and concrete examples of "otherness" it provided, and the direct contact that existed between Japan and the US in the postwar period. The Italian philosopher, Giovanna Borradori (Vassar College) once interviewed the leading American philosophers of the latter 20th century, and compiled those conversations into a book. Here is an excerpt from the section on Arthur C. Danto, with Borradori's question:

Borradori: "Many American postwar artists have taken a profound interest in the culture of the "other," especially Eastern culture. In particular, the "otherness" has been recognized as an alternative to the society of technological mass-production and consumer alienation. It is precisely in those years that you wrote Mysticism and Morality. How do you reconcile your foundationalist perspective with your interest in Eastern philosophy?"

Danto: "The East had already been in the air since the fifties. Dr. Suzuki, who after all was a great Zen master, used to teach right down the hall, here at Columbia University. I thought that Suzuki's seminars were a little like Kojeve's seminars on the "existentialist" Hegel in Paris. Everybody came to hear Dr. Suzuki, and I think Zen ideas penetrated very deeply into New York consciousness at that time. I got very involved in thinking about the East. In my book on mysticism, I remember telling about my visit to the first wonderful show of Japanese art in the immediate postwar years. Going from one room to another, I cam across a series of Venetian paintings, which I was surprised to find disgustingly fat. I could not stand that water, air, light."

The American Philosopher, p. 98

Note on machine translations of the below text, for those not familiar with Japanese: The author has input the text into Google Translation and found the quality of the translation to be extremely poor, reminiscent of the anecdote about translating the Russian phrase for "The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak” into English as “The vodka is good but the meat is rotten." While machine translations between Indo-European languages may succeed in conveying the gist of one text into the language of another, a lot of work still needs to be done to improve the quality of Japanese to English translations (the quality of English to Japanese seems to be better), especially in terms of syntactic complexity and the recognition of set literary phrases.

.

ジェームズ・ミッチェナー

解説本『北斎漫画』

と

アメリカにおける

「ジャポニスム・ルネサンス」

(1955年~1985年)

青山 康高

(ジャポニスム・ミュージアム館長)

ピューリッツァー賞受賞者でもあるアメリカの小説家ジェームズ・ミッチェナー (1907年-1997年) は、40冊以上の長編「ファミリー・サーガ」という何世代にも渡る、ある家族の遍歴を筋とした大河小説の作者として知られている。約7500万冊という驚異的な売り上げを誇る、当時一二を争うベストセラー作家であった。

実は、あまり知られていないことだが、彼はその他にも日本の浮世絵に関する書を何冊も著わしている。その一冊『The Hokusai Sketchbooks (北斎のスケッチブック)』(1958年) は、北斎漫画の解説本だが、彼の浮世絵・版画の評論のなかでは、この一冊が彼自身にとって最も親身に感じていたらしい。

この書には興味深い経緯がある。ミッチェナーはその原稿を持って、太平洋飛行中に墜落事故に遇い、運良く命拾いをしたが、その際、原稿は太平洋に消散してしまったのである。彼は大いに落胆した末、全文を新たに書き直すことを決心し、これを実行する。そのような苦心の作であったにも関わらず、彼は序章に、

「人生でここまでの喜びを抱いて原稿の執筆に取りかかったことはない

(I have never worked on any manuscript with more joy)」

と断言する。それは、より多くの読者と北斎漫画が彼に与えた想像力の羽ばたき・心の開放感を分かち合いたかった――そのような心情が、彼の解説を読むうちに伝わってくるのである。ミッチェナーは人物としての北斎にも強く惹かれ、西洋の美術史において北斎のような

「生命への壮大なる肯定(magnificent affirmation of life)」

を表現し得た者は、16世紀のピーテル・ブリューゲル以外にいないとまで結論づけている。が、個人的には、北斎の作品の方を好むとミッチェナーは付け加えるている。

このように、日本の歴史人物や文化への躊躇なき絶賛は、以前の戦中・戦後間もない時代なら、敵国を賞賛するのと同様、愛国心に欠けると見なされ、肩身の狭い思いを虐げられることになったであろう。だが1950年代に入ると、国際情勢が大きく変貌していく。そして文学や美術の流行は、政治や経済、変化する国際関係と無縁ではない。ある文化に対する人々の感受性も、それらの波動を受けて変化していくものである。ソビエト連邦との冷戦が深刻化する1950年代半ばからは、共にその脅威に立ち向かう同盟国としての日本といった新しい認識は、ミッチェナーに限らず多くの作家や芸術家が日本に関心を表明し日本的要素を己の作品に取り入れ、日本を訪れやすいようにした要因の一つであろう。

第二次世界大戦の前夜から一時頓挫した社会現象としてのジャポニスムが、再び盛り返す1950年代から1980年代前半までのおよそ30年間の間を、いわば「ジャポニスム・ルネッサンス」と名付けても、過言ではないほど日本ブームがその時代に巻き起こったのである。

しかし正確に言えば、それ以前の1930年代末から1940年代を通して、日本文化への関心が完全に途絶えたわけではない。日本に目を向ける一握りの作家やアーティストがいたということは、プリンストン大学のアール・マイナーが『The Japanese Tradition in British and American Literature(英米文学における日本の伝統)』(1958年)で明らかにしている。が、そうした日本のインスピレーションを言いふらすことはなく、世間の知るところではなかった。当時としてはこのプリンストン大学教授の珍しい研究テーマの論文「文学のジャポニスム」が、ちょうど肝心な時期にその出版計画が現れたことも、米国の高まるジャポニスムの復活を物語っているようである。マイナーが1956年をその研究領域の歴史的区切りとし、その後、続編を著わさなかったのは残念に思える。なぜならば、その直後こそに、文学及び芸術・芸能に於けるジャポニスムが、真に開花を遂げたと論じられることができるからである。

事実、1950年代後半から日本文化に通ずるアヴァンギャルド作品が次々と繰り出され、人気を博した。ジャック・ケルアックの小説、『路上』(1957年)や「仏法の浮浪者たち」という意味の『Dharma Bums』(1958年)、もしくはアレン・ギンズバーグやゲーリー・スナイダーの諸詩集に説かれた「ビート世代」の思想も、実は日本の良寛さんのような無邪気な放浪の僧、雲水・行脚の世捨て人を模倣とするものであったことは、アメリカ文化史を彩る興味深い一節である。

その後も、知覚的な変革を日本に求めるヘンリー・ミラーや、日本の戦国~江戸初期の時代を豪華な小説舞台とするジェームズ・クラベル、日本人ないし日本の技術をディストピア的な象徴として活かしたカート・ヴォネガットなど、文学における日本的要素は様々であった。そしてこの文学のジャポニスムは人種を問わず、ミッチェナー世代の作家が共有する伏流のようなものであった。白人で、南部出身の小説家ウイリアム・フォークナーは日本を訪れ、その伝統に癒やされる一方、黒人小説家リチャード・ライトは、日本の俳句を模範に、自身で歌を詠んだ。

日本の美術や精神文化は、一種の心の拠り所であった、とする米国作家の記述が散見される。意外にも、太平洋戦線で従軍し、第二次世界大戦を描いた傑作『裸者と死者』(1948年)を書いたノーマン・メイラーも、その一人かも知れない。彼は進駐軍として千葉県館山市に上陸し、そこから銚子市に移り、ここを大変気に入ったようである。その後他でも滞在したが、また銚子に戻り、帰国するまでの日々をそこで過ごした。悲惨な戦争時の体験だけでなく銚子の描写もあり、後にメイラーは日本語版の翻訳者山西英一に、「日本は私が見た国のうちでもっとも美しい国でした」と述べたようである。

ここで文学を例にディスカッションを進めてきたが、もちろんこのジャポニスム・ルネッサンスは、文学に限られた現象ではなかった。米国で広汎に、例えばコロンビア大学で通常立ち見が出る鈴木大拙の禅講座もこの現象の一つであり、また、柔道その他の武道への庶民的関心にも現れた。1960年代には、ホームドラマの典型『I Love Lucy』にも柔道が登場した。テレビに関しては、その当時、日本アニメ『マッハGoGoGo (米タイトル:Speed Racer) 』はハリウッド製作の『The Flintstones』と肩を並べる、全米の子どもたちの放課後のお気に入りのテレビ番組となった。また米映画界でも、日本は注目の的であった。例えばスティーブン・オカザキのドキュメンタリー映画、『Mishima: The Last Samurai』(2015年)で登場する大物プロデューサー、スティーブン・スピルバーグや、マーティン・スコセッシ、その他この映画の中で取り上げられるジョージ・ルーカスやフランシス・フォード・コッポラ(つまり最も優秀なハリウッドディレクターやプロデューサーの大半)の、三船敏郎や黒澤明に関する記述のみを通しても、当時彼らが抱いた邦画への情熱的関心が、押し迫るように伝わってくる。

1970年代には、ビジネスや行政、技術、社会的制度や仕組においても、日本は模範とされ、「日本から学べ」という諸説が唱えられた。芸術の枠を超えた、学問やビジネスカルチャーを動かす力となった。起業家の間でも、日本の信奉者が多く現れ、アップルの創立者スティーブ・ジョブズもその一人であった。当時のアメリカに滞在経験のある者なら、この日本を世界一と見なす『ジャパン・アズ・ナンバーワン』(1979年、ハーバード大学のエズラ・ヴォーゲル著)現象に覚えはあるはずだ。

しかしながら、1980年代が進むにつれ、日本がアメリカを追い越すか否かと騒がれ、日米貿易摩擦が更に悪化すると、ジャポニスムの勢いは(戦時中のようにまで衰えることはなくとも)、やはりその熱意の絶頂が過ぎたかのように見えるのであった。

参考文献

Aoyama, Yasutaka. 'Charles and Ray Eames' Architectural Juxtapositions. Unpublished lecture series given at Kyoto University, 2015-1016. See online on this website, 'University Lectures'.

Arnold, Wayne E. 'Henry Miller and Japonisme: 'Movement from Afar' Delta: Studies on Henry Miller, Anais Nin and Lawrence Durrell, No. 12, pp. 3-13. The Henry Miller Society of Japan, 2021.

Borradori, Giovanna. The American Philosopher: Conversations with Quine, Davidson, Putnam, Nozick, Danto, Rorty, Cavell, MacIntyre, and Kuhn. Translated by Rosanna Crocitto. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1994.

Blyth, H.R. Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics. Tokyo: Hokuseido Press, 1942.

Clavell, James. Shogun. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1975.

Christy, Arthur E. (ed.) The Asian Legacy and American Life. New York: The John Day Company, 1942, 1943, 1945.

Faulkner, William and the U.S. Information Agency. Impressions of Japan – 1955. https://legacy.catalog.archives.gov/id/51673. French language version, Estampes japonaises par William Faulkner. https://www.ina.fr/ina-eclaire-actu/video/vdd09016268/estampes-japonaises.

Faulkner, William. 'Nihon no Insho (Impressions of Japan)'. Translated by Tatsunokuchi Naotaro (龍口直太朗). Mainichi Shimbun, August 21, 1955 (Sunday).

'Fritz Perls and Gestalt Therapy, Summary for Psychology 307, Humanistic, Existential & Transpersonal Psychology' at www.sonoma.edu/users/d/daniels/Gestaltsummary.html. Accessed 2002/05/23. The founder of 'Gestalt Therapy' stayed at a Zen monastery, (like many other artists and thinkers in the early 1960's) and incorporated ideas from it into his methodology. Much of modern personality and clinical therapy theory and approaches have incorporated philosophical concepts from Japan, as well as from Chna and India.

Haneda, Michiko (羽田 美地子). ジャポニズム小説の世界―アメリカ編 (The World of the Japonisme Novel--America). Tokyo: Sairyusha, 2005.

Kerouac, Jack. The Dharma Bums. New York: Viking Press, 1958.

Lancaster, Clay. The Japanese Influence in America. New York: Walton H. Rawls, 1963.

‘Lucas and Coppola on Kurosawa’. Youtube, James Bradford Huston Music. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rN7jzqK21JE.

Michener, James A. The Floating World. New York: Random House, 1954.

_________________. The Hokusai Sketchbooks: Selections from the Manga. Rutland, VT: Tuttle Co., 1958.

_________________. Japanese Prints: From the Early Masters to the Modern. Rutland, VT: Tuttle Co., 1959.

_________________. The Modern Japanese Print. Rutland, VT: Tuttle Co., 1962.

Michener, James A.(text) and Levine, Jack (illustrations). Facing East. New York: Random House, 1970.

Miner, Earl. The Japanese Tradition in British and American Literature. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1958.

Oe, Kenzaburo. ‘Japan's Dual Identity: A Writer's Dilemma.’ World Literature Today, Vol. 62, No. 3, Contemporary Japanese Literature (Summer, 1988), pp. 359-369. Contains a discussion of Kurt Vonnegut's use of Japanese individuals in his novels.

Okazaki, Steven, director. Mishima: The Last Samurai. 2015. Documentary film, 80 minutes. Starring Mifune Toshiro (archival footage), Kurosawa Akira (archival footage), Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese; narrated by Keanu Reeves.

Pirsig, Robert. Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. New York: William Morrow and Co., 1974.

Rexroth, Kenneth. One Hundred Poems from the Japanese. New York: New Directions, 1955.

Sheppard, W. Anthony. ‘Japonisme and the Forging of American Musical Modernism’ in Extreme Exoticism: Japan in the American Musical Imagination. Oxford Univ. Press, 2019.

Suzuki, D.T.; Fromm, Erich; De Martino, Richard. Zen Buddhism & Psychoanalysis. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960.

Wright, Richard. Haiku: This Other World. New York: Arcade Publishers, 1998.

************

2021/10/28

H. G. Wells' Utopian Samurai

'Bushido Japonisme'

in

Literary Utopianism & Political Idealism

Yasutaka Aoyama, PhD

“It was several hundred years ago that the great organisation of the samurai came into its present form.

And it was this organisation's widely sustained activities that had shaped and established the World State in Utopia.”

H.G. Wells, A Modern Utopia, Chap. 9 'The Samurai', p. 261

"For it is quite clear, in my mind, that these samurai form the real body of the State.“

A Modern Utopia, Chap. 9 'The Samurai', p. 277

So wrote H.G. Wells in 1905, a man whose visions of the future were often prophetic, and which still have a hold on us today. For who has not seen a film that is based on, or at least taken a hint from The War of the Worlds, The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, or The Invisible Man? Yet few know that, riding on the crest of a full-blown British craze for Japan in the early 20th century, the creed of the Japanese samurai played a critical part in Wells’ vision of an ideal future world, as described his novel, A Modern Utopia. Though hardly discussed nowadays, in its time it was "instantly hailed as one of the great revolutionary works of modern history" (Hirschfield p.55), and highly acclaimed by his literary peers. From Henry James came:

"Bravo, bravo, my dear Wells!"

while Joseph Conrad praised its "intellectual kindliness"; Lewis Mumford called it the "quintessential utopia" (in Hillegas p.64, 66); and the eminent psychologist William James saw it prodding the next generation towards good. It even influenced that archdean of psychological conditioning, B.F. Skinner, in formulating his own version of utopia, Walden Two. It was nothing less than "central to the development of the utopian tradition in the 20th century," according to Mark Hillegas, one of the foremost scholars on Wells, who concludes: "No wonder that Utopian came to mean Wellsian for men like Forster, Huxley, and Orwell." And it was praised not only for its ideas, but its artistry as well. The renown literary critic of the day, Van Wyck Brooks, called it:

"a beautiful Utopia, beautifully seen and beautifully thought" (in Hillegas p.64)

But let us quote Wells himself, arranging his prose like verse:

"About it go planets, even as our planets, but weaving a different fate,

and in its place among them is Utopia,

with its sister mate, the Moon.

It is a planet like our planet,

the same continents, the same islands, the same oceans and seas,

another Fuji-Yama is beautiful there

dominating another Yokohama... "

(Wells p.13)

Japan as Utopia

Since the time of Marco Polo, Japan as a world apart, imbued with utopian qualities, has been an idea that has lured a colorful variety of men towards it as different as Christopher Columbus, Rudyard Kipling, and Steven Jobs. Over time, Jesuits and later travelers added to the mystique by writing a slew of books on discovering Japan---as a place of the unexpected, of the profoundly different---a quasi-mythical land. Thus Francis Bacon's New Atlantis begins with Japan as one of the original destinations; Jonathan Swift sent Gulliver to Japan on his third voyage; in Melville the seas of Japan are Moby Dick’s playground. It represented the opposite of whatever was mundane, and as Hawthorne would write “there could hardly be a less hackneyed theme than Japan”. (in Miner p.18) Whether a land glittering in treasures or serene spirituality, or much later a juggernaut of economic and social efficiency, Japan was, not only in the West, but in countries of Asia as well, the symbol of the extraordinary---whether good or bad.

One of those idealized visions of Japan has revolved around the samurai, the warrior class of feudal Japan. We might call it the Japonisme of the samurai and their code of bushido. But we should really separate the two: ‘Samurai Japonisme’ to refer to the general influence of samurai imagery and martial arts; reserving ‘Bushido Japonisme’ for the influence of samurai personalities and their bushido code as a model for leadership and character building, as a moral and political ideal. For the samurai as gentleman, not just as warrior, has had an impact on the world’s ideas about Virtue and Idealism much greater than most people realize.

What we look at here is H.G. Wells’ (1866-1946) brand of utopia or an ideal society, and the role the samurai had in it; whether he simply borrowed the term as an eye-catching device (as book reviews and internet summaries would have it), or if he incorporated the ideas behind the name, that is the ethos of bushido, into his conception of utopian leadership and virtue.

The quick answer is: yes---his utopian ‘samurai’ can be recognized as akin to their Japanese counterparts. We find much in common in his writing with the prevalent ideas about the samurai that had reached Europe just a few years earlier; two books were particularly influential in Western conceptions of bushido at the time:

1) Uchimura Kanzo’s (1861-1930) Japan and the Japanese. Essays, published first in English, in 1894 (republished as Representative Men of Japan, 1908), and often noted to have been admired by prominent public figures, including President Theodore Roosevelt, President John F. Kennedy, and Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scouts. Interestingly, in the 1911 edition, Japan is the first specific example in ‘Scout Law’ of the Boy Scout Handbook, distributed to every boy scout:

“In Japan, the Japanese have their Bushido or laws of the old Samurai warriors.” (Chap 1, Scout Law)

2) Nitobe Inazo's (1862-1933) Bushido: The Soul of Japan, also first published in English, in 1899, likewise admired by Teddy Roosevelt. Nitobe in later editions comments how flattering “is the news that has reached me from official sources, that President Roosevelt has done it undeserved honor by reading it and distributing several dozens of copies among his friends.” (10th edition preface, in the 13th edition, p.X)

Both Uchimura and Nitobe’s books went through many reprintings, and were translated into many languages. And while both contain a strong strain of visionary idealism, here it will be the latter, Nitobe’s Bushido, that we shall hold up as the mirror to Wells’ utopian samurai.

Firstly, there should be no doubt about the central importance of the samurai in Wells’ novel, a point repeatedly emphasized by the main character: “...I am inclined now at the first onset of realisation to regard it as far more significant than it really is in the Utopian scheme, as being, indeed, in itself and completely the Utopian scheme.” (Wells 9.1 p.259) And some pages later, it is the “...samurai, in whose hands as a class all the real power of the world resides.” “Ah!” said I, “ and now we come to the thing that interests me most." (Wells 9.3 p.277)

Like Wells, Nitobe emphasizes the samurai as the guiding principle of the nation: “What Japan was she owed to the samurai. They were not only the flower of the nation but its root as well. All the gracious gifts of Heaven flowed through them. Though they kept themselves socially aloof from the populace, they set a moral standard for them and guided them by their example.” (Nitobe 1900 p.147---henceforth all Nitobe page numbers will be from this edition)

Let us now delve further into Wells and Nitobe’s ideas of the samurai, letting them speak mainly for themselves:

Bearing and Self-Restraint à la Japonaise

Starting with appearances and first impressions, like the image of samurai, otherwise known as 'bushi' of Edo period Japan, in Well’s Utopia there are:

“certain men and women of a distinctive costume and bearing, and I know now that these people constitute an order, the samurai, the “voluntary nobility,” which is essential in the scheme of the Utopian State.” (Wells 9.1 p.259)

His twist is that the samurai are a 'voluntary' nobility, but otherwise, if we take a deeper look, much like the bushido code, there is a “prescribed austere rule of living” and an assumption that self-sacrifice in men and the self-management of desires is expected, reminiscent of Zen-influenced samurai behavior where:

“self-seeking is no more the whole of human life than the satisfaction of hunger; that it is an essential of a man's existence no doubt, and that under stress of evil circumstances it may as entirely obsess him as would the food hunt during famine, but that life may pass beyond to an illimitable world of emotions and effort.” (Wells 9.1 p.261)

—Or as Nitobe says, much in the same vein, that it was:

“SELF CONTROL which was universally required of samurai. The discipline of fortitude on the one hand, inculcating endurance without a groan, and the teaching of politeness on the other, requiring us not to mar the pleasure or serenity of another by manifestations of our own sorrow or pain, combined to engender a stoical turn of mind, and eventually to confirm it into a national trait of apparent stoicism.“ (Nitobe pp.66-67)

Maintenance of Samurai Dignity and Refinement

For Wells’ samurai, as for samurai in the Edo period, that which was ignoble ('gehin') or lacking in dignity were forbidden, such as acting or singing in public:

“Acting, singing, or reciting are forbidden to them, though they may lecture authoritatively or debate. But professional mimicry is not only held to be undignified in a man or woman, but to weaken and corrupt the soul; the mind becomes foolishly dependent on applause, over-skillful in producing tawdry and momentary illusions of excellence; it is our experience that actors and actresses as a class are loud, ignoble, and insincere.” (Wells 9.5 pp.289-290)

We find the explanation in Nitobe, who goes over various terms that refer to avoidance of disgrace known as 'haji':

“...na (name) men-moku (countenance), guai-bun (outside hearing) ... A good name---one’s reputation, the immortal part of one’s self, what remains being bestial---assumed as a matter of course, any infringement upon its integrity was felt as shame, and the sense of shame (Ren-chl-shin) was one of the earliest to be cherished in juvenile education. “You will be laughed at,” “It will disgrace you,” “Are you not ashamed?” (Nitobe p.45)

Elsewhere Nitobe and Wells speak of the role of pride, but we might add the importance attached to ‘hokori’ (sentiment of honor, dignity beyond calculable value) something more than just pridefulness, as well as the value of ‘hinkaku’ (refinement, grace).

A Transition from an Age of Conflict to Peace

Interestingly, Wells hints the samurai were once fine swordsmen: “For a time, most of the samurai had their sword-play, but few do those exercises now, and until about fifty years ago they went out for military training...” (Wells 9.5 p.292)

Wells’ samurai are no longer a military force, but the samurai’s warrior connotation remains. The “...samurai, who began as a private aggressive cult, won their way to the rule of the world. “I would like to have that history,” I said. “I expect there was fighting?” He nodded.” (Wells 9.4 p.279)According to Wells, they evolved into “a more militant organization” and, reminiscent of Japan’s transition from an age of warring factions to one of unification (戦国から太平の世へ), so too, Wells’ samurai “...prevailed against and assimilated the pre-existing political organisations, and to all intents and purposes have become this present synthesised World State.” (Wells 9.1 p.262) And while those militant aspects would be less utilized in a peaceful world utopia, like the idea of bushido in an age of Tokugawa peace,

“Traces of that militancy would, therefore, pervade it still, and a campaigning quality---no longer against specific disorders, but against universal human weaknesses, and the inanimate forces that trouble man---still remain as its essential quality.” (Wells 9.1 p.263)

This reminds us of Nitobe quoting a certain Mr. Mallock, who claims historical progress is produced by a struggle “not among the community generally, to live, but a struggle amongst a small section of the community to lead, to direct, to employ, the majority in the best way.” To which Nitobe comments:

“Whatever may be said about the soundness of his argument, these statements are amply verified in the part played by bushi in the social progress, as far as it went, of our Empire.” (Nitobe p.108 bold print by this author)

Thus, while Wells’ hypothetical samurai unite and lead the entire world forward, the real-world samurai of Nitobe have played a similar role in the actual social progress of the Japanese Empire.

Echoes of ‘Bunbu Ryodo’ (proficiency in both arms and letters)

The reality of samurai life and activity during the Japanese Edo period is not all that different from what Wells describes in his utopia, as the actual samurai were a more numerous part of the population than the aristocracy was in Europe: “Our Founders put it that a candidate for the samurai must possess what they called a Technique, and, as it operated in the beginning, he had to hold the qualification for a doctor, for a lawyer, for a military officer, or an engineer, or teacher, or have painted acceptable pictures, or written a book, or something of the sort.” Wells 9.4 p.282) Of course not all Japanese samurai had a 'technique'; rather, among them were always those who had specialty knowledge, contrasting to the case of nobility in Europe, where specialists (as different from scientists who were considered philosophers) were generally from outside the aristocracy before the 19th century. Also, the painting of pictures was considered an appropriate pastime for the samurai of the Edo period, though not as a profession.

The samurai of Wells' Utopia combine a militant bent with intellectual/literary/artistic talent in a ‘bunbu-ryodo’ (文武両道 proficiency in both arms and letters) fashion. Just as the Edo period samurai were admonished not to slacken in their physical discipline, so for Wells’ utopian samurai, “Next to the intellectual qualification comes the physical, the man must be in sound health, free from certain foul, avoidable, and demoralising diseases, and in good training.” (Wells 9.5 pp.284-285) And they are guided by a set of samurai rules, somewhat reminiscent of various Edo period samurai rules such as the ‘Buke Hatto’ (武家法度) mentioned by Nitobe (p.4) and ideas of body and mind training (心身共に鍛える---this author's observation): “The Rule aims to exclude the dull and base altogether, to discipline the impulses and emotions, to develop a moral habit and sustain a man in periods of stress, fatigue, and temptation, to produce the maximum co-operation of all men of good intent, and, in fact, to keep all the samurai in a state of moral and bodily health and efficiency.“ (Wells 9.4 p.279-280) Obviously nobles in Europe trained their bodies and prayed, but this is much more than that. It is a highly codified regimen with a psychological awareness more along the lines of samurai martial arts.

A Confucian-style Education

Sounding much like the five classical books of Confucian learning, in Wells’ Utopia there is also a body of canonical works:

“The Canon pervades our whole world. As a matter of fact, very much of it is read and learnt in the schools.” (Wells 9.4 p.284).

“Our Founders made a collection of several volumes, which they called, collectively, the Book of the Samurai, a compilation of articles and extracts, poems and prose pieces, which were supposed to embody the idea of the order.” (Wells 9.4 p.282-283)

---just as there are books of poems, prose, and articles that comprised Chinese classics-based Edo period samurai education. Wells’ utopian values are along the lines of order, rationalism, and deism, where harmonious relationships among people, and between the universe and the individual, could be achieved by human effort---somewhat along the lines of Tokugawa Neo-Confucianism, known as 'Shushi-gaku' (朱子学).

In fact the system for recruiting elites sounds also Japanese, or at least Far Eastern. Wells even has a sort of 'ronin' student system, where applicants can try over and over again, year after year: “And so anyone who has failed to pass the college leaving examination may at any time in later life sit for it again---and again and again.“ (Wells 9.4 p.281) It may have been that Wells was also incorporating features of contemporary Japanese Meiji society he had heard of, as material to flesh out his vision of Utopia.

The Virtue of ‘Kinben’ (Diligence) and the Practice of Reading Aloud

Like samurai sons in Japan having to read aloud (素読 sodoku) spiritually elevating works, we find Wells’ samurai also (though there is an added twist of new recent publications on the required reading list as well):

“...must read aloud from the Book of the Samurai for at least ten minutes every day. Every month they must buy and read faithfully through at least one book that has been published during the past five years, and the only intervention with private choice in that matter is the prescription of a certain minimum of length for the monthly book or books. But the full Rule in these minor compulsory matters is voluminous and detailed, and it abounds with alternatives.” (Wells 9.6 p.297)

The Japanese idea of not only comprehending content, but emphasizing the practice, form, and habit of reading as being critical to nurturing character and the communal bond, is also found in Wells:

“Its aim is rather to keep before the samurai by a number of sample duties, as it were, the need of, and some of the chief methods towards health of body and mind, rather than to provide a comprehensive rule, and to ensure the maintenance of a community of feeling and interests among the samurai through habit, intercourse, and a living contemporary literature.” (Wells 9.6 p. 298)

Or as Nitobe puts it in his section on the “Education and Training of Samurai”:

“...it was not objective truth that he strove after, ---literature was pursued mainly as a pastime, and philosophy as a practical aid in the formation of character.” (Nitobe p.61)

Conceptualizations of a Hierarchical Society for Utopia

While the historical samurai society based on functional categories contrasts with Wells’ utopian samurai society divided into psychological categories, those psychological types are still closely related to their functions in society. The 'Shi-No-Ko-Sho' (士農工商samurai-farmer-craftsman-merchant) four divisions of society in the Japanese system also were assumed to reflect a different set of values, abilities, and psychological makeup appropriate to each group.

In Wells’ Utopia: “Four main classes of mind were distinguished, called, respectively, the Poietic, the Kinetic, the Dull, and the Base. The former two are supposed to constitute the living tissue of the State; the latter are the fulcra and resistances, the bone and cover of its body.” (Wells 9.2 p.265) The nature of his classes can be somewhat guessed; obviously the first two are preferred over the latter. Wells’ samurai are of the Poietic and Kinetic, somewhat corresponding to a Japanese idea of an imaginative Bun (文・文才) and an active Bu (武・武勇); and undertake most of the managerial and intellectual tasks just as the real samurai did:

“Typically, the samurai are engaged in administrative work. Practically the whole of the responsible rule of the world is in their hands; all our head teachers and disciplinary heads of colleges, our judges, barristers, employers of labour beyond a certain limit, practising medical men, legislators, must be samurai, and all the executive committees, and so forth, that play so large a part in our affairs are drawn by lot exclusively from them.” (Wells 9.4 p.278)

The samurai of both Wells and Nitobe do much more than the nobles of Europe, as they function in almost all aspects of social regulation, from petty administration to large-scale construction, from literary education to even mechanical oversight. Let us not forget every bushi was expected to be able to write a line of poetry, even at the moment before self-inflicted death. In Europe there was a greater divide between the sword and the pen when compared to Japan; what we might even call an anti-intellectual attitude existed among sportive British nobles. Scribes were not of nobility, and given there were those with literary talent (like Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford), scholarship was for clergy and not for aristocrats until the 18th century, though of course there must be exceptions. Even in the latter 18th century, we might recall with a chuckle, Edward Gibbon being heckled by the Duke of Gloucester regarding his opus magnum, The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire:

“Always scribble, scribble, scribble! Eh? Mr. Gibbon?” (Sutherland #159 p.109)

Disdain for Money and Disassociation from Commerce

Commerce and finance are given low status in Wells, as in Nitobe, despite English aristocratic society becoming receptive to financial and merchantile activity relatively early on (Chapman 1986), and certainly compared to Japan. Nitobe says of samurai society: “Of all the great occupations of life, none was farther removed from the profession of arms than commerce. The merchant was placed lowest in the category of vocations…” (Nitobe p.39) As for money: “He disdains money itself, ---the art of making or hoarding it. It is to him veritably filthy lucre. ... It was considered bad taste to speak of it, and ignorance of the value of different coins was a token of good breeding.” (Nitobe, p. 63) The regard of Wells’ utopian samurai for money is similar:

“The idea of a man growing richer by mere inaction and at the expense of an impoverishing debtor, is profoundly distasteful to Utopian ideas...” (Wells 9.5 p.287)

“Originally the samurai were forbidden usury, that is to say the lending of money at fixed rates of interest. They are still under that interdiction, but ... it is now scarcely necessary.” (Wells 9.5 p.287) Money lending of course, was forbidden to the samurai of Japan. And Wells goes on to give an explanation that would serve, almost word for word, for a history of Edo period samurai attitudes and rules regarding commerce. Here is an excerpt:

It is felt that to buy simply in order to sell again brings out many unsocial human qualities; it makes a man seek to enhance profits and falsify values, and so the samurai are forbidden to buy to sell on their own account or for any employer save the State, ...and they are forbidden salesmanship and all its arts.” (Wells 9.5 p.287)

Wells adds: “I suppose no samurai may bet?” The answer of course is: “Absolutely not.” (Wells 9.5 p.290) Indeed, sometimes we can hardly distinguish Wells’ utopian leaders from feudal Japan’s ruling class in these matters.

The Mirroring of Shinto Belief

Nitobe lists Shinto religion as an important source of bushido, and its core value, he explains, as inborn goodness, without original sin:

“Shinto theology has no place for the dogma of original sin.

On the contrary, it believes in the innate goodness and the God-like purity of the human soul...” (Nitobe p.8)

So Wells says:

“The leading principle of the Utopian religion is the repudiation of the doctrine of original sin;

the Utopians hold that man, on the whole, is good. That is their cardinal belief.” (Wells 9.7 p.299)

Sometimes with similar wording, sometimes more fully recast, but getting across the same message, we find various religious ideas outlined in Nitobe paralleled in Wells’ ideas of utopian spirituality.

Shinto-like Rituals of Purification and Conceptions of Health

Nitobe says, “Occasional deprivation of food or exposure to cold, was considered a highly efficacious test for inuring them to endurance.” (Nitobe p.20) In Wells, that idea is combined with ideas reminiscent of Shinto religious concepts and rituals of purification and vitality, as well as the avoidance of 'kegare' (pollution/taint): “the samurai must bathe in cold water and the men must shave every day; they have the precisest directions in such matters” the body must be in health, the skin and muscles and nerves in perfect tone, or the samurai must go to the doctors of the order, and give implicit obedience to the regimen prescribed.” (Wells 9.6 p.297)

Meditation and ‘Shugyo’

Wells’ samurai also mix Zen-type meditation and something similar to Shugendo (mountain asceticism) or ajari (Buddhist teacher) style 'shugyo' (physically demanding, often outdoor, training for spiritual advancement):

“But the fount of motives lies in the individual life, it lies in silent and deliberate reflections, and at this, the most striking of all the rules of the samurai aims. For seven consecutive days in the year, at least, each man or woman under the Rule must go right out of all the life of man into some wild and solitary place, must speak to no man or woman, and have no sort of intercourse with mankind.” (Wells 9.7 p.302-303)

In Nitobe’s chapter ‘Sources of Bushido’ the first source to be raised is Zen Buddhism: '"Zen" is the Japanese equivalent for the Dhyana, which "represents human effort to reach through meditation zones of thought beyond the range of verbal expression." Its method is contemplation, and its purport, as far as I understand it, to be convinced of a principle that underlies all phenomena, and, if it can, of the Absolute itself, and thus to put oneself in harmony with this Absolute.”' (Nitobe pp.7-8) Zen emphasizes the personal experience of truth, away from distractions, where each man’s meditation and realizations of a greater unity are his alone; so too in Wells’ utopian religion: “The aspect of God is different in the measure of every man’s individuality, and the intimate thing of religion must, therefore, exist in human solitude, between man and God alone." (Wells 9.7 p.302)

Traditional Japanese Dietary Habits and ‘Sessho’ interdictions

The below hardly needs explaining. Its similarity to traditional Japanese cusine and the Buddhist interdiction against 'sessho' (殺生), or the unnecessary taking of four-legged life for nourishment is evident:

“In all the round world of Utopia there is no meat. There used to be. But now we cannot stand the thought of slaughter-houses. And, in a population that is all educated, and at about the same level of physical refinement, it is practically impossible to find anyone who will hew a dead ox or pig. We never settled the hygienic question of meat-eating at all. This other aspect decided us. I can still remember, as a boy, the rejoicings over the closing of the last slaughter-house.”

“You eat fish.” (Wells 9.5 p.286)

‘Hara hachibu’ and Pride/Dignity in Hunger

Likewise, attitudes toward eating also reflect samurai pride and restraint. Concepts of eating in moderation ‘hara hachibu’ (腹八分 literally 8/10ths full) or learning how to curb one’s excesses ’taru wo shiru’ (足るを知る) and ‘bushi wa kuwanedo takayouji’ (武士は食わねど高楊枝), meaning keeping one’s head high (literally one’s toothpick) even in extreme hunger, are reflected in Wells’ utopia:

“Our Founders organised motives from all sorts of sources, but I think the chief force to give men self-control is Pride. Pride may not be the noblest thing in the soul, but it is the best King there, for all that. They looked to it to keep a man clean and sound and sane. In this matter, as in all matters of natural desire, they held no appetite must be glutted, no appetite must have artificial whets, and also and equally that no appetite should be starved. A man must come from the table satisfied, but not replete.” (Wells 9.5 p.293-294)

Samurai Social Decorum: Restraint in Clothing, Care of Coiffure, and Elaborate Rules of Attire

Wells' samurai men and women dress somewhat alike, and even if to the Japanese themselves male and female kimonos might seem exceedingly different, they appear to Westerners as much more alike compared to the stockings and tights or tapering pants of men versus long and wide skirts of women that were typical of English aristocratic dress up to the 19th century (in fact the growing comfort of men's dress in the West, with kimono inspired gown-like coats is another aspect of japonisme, which we cannot cover here).