Architectural Japonisme VI

建築のジャポニスム VI

1. Paul T. Frankl: Japonisme in Art Deco Design

With References to Kunisada III, Hashimoto Sadahide, NIshitani Ichisuke, Sugawara Seizo, Jean Dunand, Eileen Gray, Suzuki Harushige, Utagawa Yoshiharu, Donald Deskey, Georges Lamoussu, Yoshida Tetsuro, and Edward Durell Stone

2. Richard Neutra's Conceptual Japonisme

With References to Gary Snyder, Kaneji Domoto, Joseph Eichler, Steven Ehrlich, and Christopher Robertson

3. Rudolph Schindler's Schindler/Chace House

Recreating Japan for his Own Home

Image: IONOS

Uploaded 2024.7.29. Under construction

Paul T. Frankl (1886-1958)

Japonisme in Art Deco Design

Yasutaka Aoyama

"Of the early Los Angeles moderns, the one who had the most direct contact with Asia was Paul T. Frankl. Frankl visited Japan twice, once in 1914 and again in 1936. He also made a hasty buying trip to China in 1939. Far more than Schindler or Harris, Frankl also made a concerted effort to learn about Japanese design philosophy. During his first sojourn in Japan, which took him to Tokyo (he stayed in a traditional inn, not far from the future site of Wright’s Imperial Hotel), then on to Nara, Osaka, and Kyoto, he was careful to observe all he could. And while in Kyoto, he had lessons in Japanese flower arranging, a skill he would use for the remainder of his career." ---So writes Christopher Long, at the University of Austin, Texas, the foremost authority on Paul T. Frank ('Asian Influences and the Rise of Southern California Modernism', Nonsite.org, Issue 43, June 16, 2023, at nonsite.org), and whose research, besides the writings of Frankl himself, we will rely upon for the most part in this discussion.

"Viennese émigré Paul T. Frankl (1886-1958) was one of the pioneers of early modern design in the United States, known for his “Skyscraper” furniture of the 1920s and his work for the Hollywood élite in the 1930s and early 1940s." (C. Long, 'Paul T. Frankl Autobiography', Nov. 2013, at soa.utexas.edu). Frankl is representative of Art Deco design in America, which saw its heyday between 1925-1940, a movement which, like the Art Nouveau movement before it, was intimately connected with contemporary architectural styles, and no less inspired by Japanese art---but by a different, though equally important set of Japanese design qualities. For while Art Nouveau was influenced by the highly organic and ornate forms of Japanese art, as seen in sacred architecture and sculpture, as well as pottery and prints, the Art Deco movement focused upon the minimalist and angular forms of Japanese residential architecture, furnishings, screens, and lacquerware design---though we must add the caveat that both Art Nouveau and Art Deco often took from similar Japanese arts or crafts, such as kimono design, with each focusing on different styles within that particular artistic medium.

And while modernist architecture is treated separately from Art Deco, there is no doubt that the two overlapped not only in time but in space, and converged towards each other conceptually and stylistically. Both Modernist architecture and Art Deco accentuated horizontality and verticality; angularity; streamlined or minimalist approaches; saw themselves as willing children of industrial modernity; and incorporated many aspects of Japanese design.

Long discusses Frankl's interest in Japanese design and culture in general terms, but he does not point out the specific links, in terms of form and concept, that exist between Frankl's designs and those of Japan. The following are a few concrete examples of the character of Frankl's japonisme; I leave the reader to do his own perusal of Frankl's books and his product listings, who will surely recognize many more of Frankl's designs that were inspired by Japan, if he should have studied Japanese art and architecture in earnest.

Skyscraper Furniture: The Japonisme of Asymmetry, Stacking and Staggering, and the Intersecting Right-Angle

"Frankl’s later Skyscraper bookcases and desks, which catapulted him to fame in the mid-1920s, were based in part on Japanese Sendai chests, which he came to appreciate during his first Japan trip."---(Long, 'Asian Influences' Nonsite.org, Issue 43, June 2023, at nonsite.org) Just how they were based upon Sendai chests however, is not pursued further in Long's article, or his monograph on Frankl.

Of Frankl's 'skyscraper' furniture, his stairs-like bookcase is the most iconic of all, often included in books on the Art Deco movement. The idea seems inspired, more specifically speaking, from the Japanese kaidan-dansu (literally 'stairs cabinet' also called hako-kaidan 'stairs of boxes') and is actually used as a staircase as well in Japanese minka (farmhouse) homes, whether from Sendai or otherwise. These are common in traditional country homes in Japan, and are but one example of the tendency to create built-in, compact, and multi-purpose household furnishings and goods that result in an artistic design. The staggered effect is common not only in tansu cabinets, but also of 'chigaidana' shelves in the tokonoma, an idea also reflected in modern interiors. Long does not provide any examples of Japanese Sendai chests (仙台箪笥) or any other type of traditional Japanese furnishings which are analogous to Frankl's designs.

Examples of Kaidandansu / Hakokaidan in their Natural Setting

Note how the cabinet actually functions as the stairway to the second floor in the examples show below, which was originally the case, though often nowadays used as a decorative statement. Observe the setting: the elements of modern design---the thick, bold outlining of walls and openings unifying the design into an integrated whole, much as in the work of Hoffmann and Loos, combined with finer gridded screens/windows. Not to be overlooked are the drawers next to the kaidandansu (in the photo to the right), so completely built-in and fitted so as to leave not even a crack of space above, below, or to the sides; and in the other (left) photo, in the room beyond, is another built-in closet, flush with the walls, with its sliding panels clearly framed with black lacquer. These principles of Japanese design had been adopted by European architects contemporaneously with painters, ceramicists, and product designers who had been adopting various aspects of Japanese design in each of their respective areas.

Symmetrical Stacking

Japan has not only inspired asymmetrical designs, but also influenced the nature of symmetric designs. The extremely pronounced horizontality of lines and form, accentuated by the stacking of planes and volumes may be also considered a contribution of Japanese aesthetic verve. Japanese keshozen (化粧前), that is dressing tables or vanities, more commonly known as kyodai (鏡台 'literally 'mirror stands') looked very much like Frankl's design: often in red lacquer, of similar proportions, where the cabinet is a compact form of squat, squarish drawers on both sides unified by a board on which the mirror is fixed. It is not difficult to see how Frankl's vanity looks as if it were to be used sitting on the floor, were it to be reduced in size; he has simply magnified the measurements of a Japanese kyodai. The example to the left, is a Edo period (19th century) piece at the Osaka City Museum, which, though coming in separate pieces, conveys the same sleek horizontal lines and angular, boxy, multi-level stacked forms which Frankl, and other Japanese vanities, merge into a unified piece.

Asymmetrical Juxtapositions

Asymmetry is an often raised example of japonisme influence in Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting, and the same holds for modern architecture, as well as interior and furniture design. In fact, Japanese asymmetric design had been making a profound impression upon Europeans since the 17th century (e.g. see Constantijn Huygens in 'Japonisme of the 16th -18th Centuries, Part II'). A closer analogy, than the tsuba (sword guard) shown below from Georges de Tressan's amply illustrated 'L’évolution de la garde de sabre japonaise' (Bulletin de la Société Franco-Japonaise de Paris, June-September, 1910), would have been a Japanese 'karakuri-bako' (trick box), and could very well have been the inspiration for what he called his 'Puzzle' desks. But the spirit of liberated asymmetric design is clearly apparent in the tsuba, and is indicative of the ubiquitous nature of asymmetric juxtaposition in Japanese design, whose images were readily accessible to Western designers by the early 20th century.

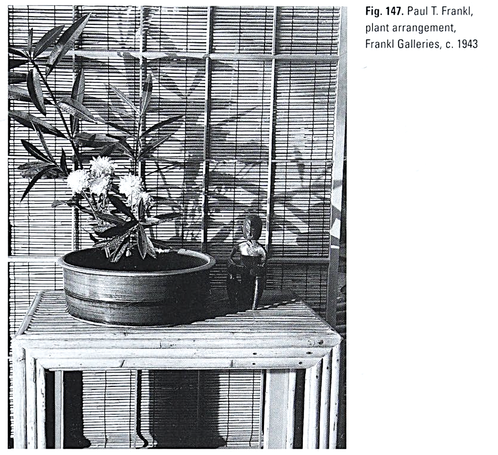

Frankl's Sudare Style

"During his time in Japan, Frankl made note of even the most trivial details of living. He wrote of the “refinement” and “dignity” he saw everywhere; he was especially struck by the “art of elimination,” which he thought posed a potent alternative to Western taste. He described it as “the distilled essence of beauty.” And he took away from his experiences an especially strong love for the Japanese “simplicity of expression” and the “ability to use materials true to their nature.” (Long, 'Asian Influences' Nonsite.org, Issue 43, June 2023.) This is reflected in his clean, almost minimalist interior designs, which will be discussed later. Another expression of this idea is Frankl's palpable love of sudare, of bamboo and rattan, applying it in his own way not only to screens, but also to furnishings.

Above right is a room with natsushoji (夏障子), very similar to sudare in construction material, in a minka in Rokusei-machi, Kashima County, Ishikawa Prefecture. "Changing doors and windows in summer and winter is an idea that goes back as far as the shinden-zukuri style of the Heian period. In winter, the room is surrounded by wooden doors, while in summer, they are replaced by open screen doors that let the breeze through. Not only does this protect the house from hot and cold, it emphasizes the pleasure of the change of seasons." (Matsuki Kazuhiro, ed., Mado---Nihon no Katachi, The Form of Japanese Windows, 1997, p. 94)

Long writes: "In his later autobiography, he wrote about his love of traditional Japanese dwelling spaces: “The Japanese house always made me feel good and living in it takes me back to my early childhood in the nursery, where life was lived on the floor. The scrupulously clean, resilient tatami mats covering the floors … are pleasant to the touch. Seated on them or on a soft, comfortable silk pillow, you have the feeling of space and elbow room.” ('Asian Influences', Nonsite.org, Issue 43, June 2023.)

Below a room with tatami floors (left) and sudare shades hanging from above. The tatami is also composed of closely aligned fine straw-like material, the igusa (イ草 rush grass), forming parallel lines, and indeed pleasing to touch. Below right: "A fine grille with bars like the thin bars of an insect cage is called "mushiko koshi (insect cage grille)". The finer strips of bamboo are called "sumushiko". People cannot look in, but from the inside, you can see outside almost effortlessly." (Matsuki, 1997, p. 101)

The Japanese art of using bamboo, reed, grass and like materials from fencing to shoji to the finest sudare, is a world of study to itself. One could easily devote a semester to its history, crafting, uses, and types. The more tightly aligned, fine Japanese bamboo/reed work was something that seems to have fascinated Frankl, for he often employed bamboo, rattan, and sudare material in varying thicknesses to his furniture and interior designs, of which a few examples are shown below.

The Japonisme of the 'Emboldened' Line

"When Frankl first began to practice in New York in 1915 (he was unable to return to Vienna because of the outbreak of the First World War), he sometimes made distinctly Japanese references in his designs. And he recreated—quite faithfully given the circumstances---a Japanese interior for the play Bushido by Takeda Izumo, which was produced by the Washington Square Players at the Bandbox Theatre in New York in 1916." (Long, 'Asian Influences', 2023)

What is interesting about Frankl's stage set is that it also reminds one of Adolf Loos' and Josef Hoffmann's interiors, in the sectionalizations of wall planes with bold outlines, delicately gridded windows, and in the uncluttered atmosphere. Next to it is a photo of a Japanese high school reception room c. 1920, with western elements as a chandelier and lace curtains (to the far right). It is clear to see that the resulting designs converge: the first one that attempts to recreate a Japanese interior in a Western cultural and material environment; the other that Westernizes a Japanese interior in the cultural milieu of Japan.

Many aspects of what is considered 'Loosian' (after Adolf Loos, see article on Loos on this website) have their precedents in Japanese architecture, or in the 'Anglo-Japanese' style of E. W. Godwin. One of those features is the differing floor levels in one continuous living space, an idea observable in the Japanese 'jodan-no-ma' (上段の間), or higher room-space vs. the 'gedan-no-ma' (下段の間) lower room-space, these being a conspicuous feature of imperial and daimyo lord residences. Further level changes occur from the jodan-no-ma to the tokonoma (picture alcove), as well as slight level changes between the engawa (balcony) vs. the interior living spaces. Also, most conspicuously, there is a very large change in level from living areas vs. the doma entry/kitchen---this all visible through and through when the screens are all slid open (and in some houses there is even a horigotatsu, a rectangular opening in the living area to drop one's feet into, thus creating level changes 'down after going up' in the house).

The fundamental kinship of spatial conceptions between Japanese and Japanese inspired Western architecture is not changed by the fact that a few more steps might be added in those level changes, as was done by Bruno Taut in his Hyuga house in Atami (1936) which, despite being treated as a novel design by Japanese architectural historians (who seem not capable of seeing fundamental equivalences or variations of a theme in designs when the slightest change of detail occurs), is primarily derivative of the Japanese with simplistic Western-style modifications. In fact, the multi-stepped change in broad platform levels existed in traditional Japanese architecture, as found in the Katsura Imperial Villa, where there are changes of level from the engawa to a higher level by way of a short stairway, for instance.

Foreigners in Japan had, in fact, been experiencing the kind of partitioned, transformable spatial environments and level transitions that are considered to be part of the modern architectural experience during their stays in Japan from the mid-19th century after the opening of the country (actually much earlier for three centuries at the Dutch Dejima colony), as the example of the Yokohama print (1863) by Hashimoto Sadahide reveals, shown below (left). Thus the underlying architectonics of a Hoffmann or Loos interior would not have been something completely novel to the thousands of Westerners who had visited Japan, or for that matter, seen ukiyo-e prints of Japanese interiors like the one below. These considerations will be important in the discussions to follow of Christopher Long's appraisal of Japanese influence upon Frankl's Coldwater Canyon House.

Regarding Nishitani Ichisuke's marvelously disconcerting Seibi-kan (center), which foreshadows modern architectural conceptions of reversals in the vertical ordering of mass (though not visible in this photo) and innovative window design, one can also discern the two tiered, high tokonoma partially visible to the lower left, which precedes Taut's design by almost two decades, and shows the evolution occurring, in line with the other images, of the idea of level changes within a visually continuous room space unhampered by floor to ceiling walls in Japan. Bruno Taut's steps, which are in a very reddish wood, by the way, though thought of as a daring innovation of his, may have taken a hint from the step-like 'hinadan' (temporary doll display rack during the hina-matsuri) of large residences, which were magnificent in their width and height, and in bright red.

Radiating and Conic/Serrated Lines

The kyokujitsu-ki flag (旭日旗), often associated with the Japanese military, was an iconic symbol recognized worldwide after the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. It was however, already a common theme in Japanese ukiyo-e prints from the Edo, and especially during the Meiji, periods, of which an example by Utagawa Kunisada III (三代 歌川 国貞 1848-1920) is shown below. A related design, also extremely popular from the Edo period in the 18th and 19th centuries and into the Meiji-Taisho period, was the dandara (だんだら) pattern of repeated serrated shapes (also reminiscent of flames or the shining points of a star or sun) first because it was used by the Ako Roshi (赤穂浪士) as their outfit in their famous adauchi (仇討 righteous revenge) of their lord in 1703, and then worn later by the Shinsengumi (新選組) in the mid-19th century, and can be seen in the same print by Kunisada III.

The Radiating and Conic/Serrated Forms Combined

As mentioned above, the radiating bands from a central disk as the sun was an omnipresent symbol in the late 19th and early 20th century Japan, associated with Japan worldwide after the Russo-Japanese war. Another popular pattern in Japan at the time, was the repeating pronounced serration, also produced in bold contrast, though unlike the radiating sun, which was commonly in red, orange, or yellow on a background of white, the dandara was depicted in white on a background of black, blue or purple. Often the dandara pattern encircled the edge of sleeves, with dramatic effect as in the ukiyo-e print by Kunisada III. This sort of graphic design can be seen in a variety of Art Deco designs, not just those of Frankl; indeed, it may be argued that even the Chrysler building in New York echoes this iconography.

Utagawa Kunisada III, Kana-tehon Chushingura Jyuni-danme (假名手本忠臣蔵 十二段目), 1890

The Ichimatsu Moyo

The ichimatsu-moyo (市松模様) is a classic wall pattern in Japanese interiors. It can be seen in the Katsura Imperial Villa, and earlier in picture scrolls. It's continued popularity into the early 20th century among Japanese architects can be detected in Yoshida Tetsuro's interior for the Baba House in Ushigome, Tokyo (1928), published in Yoshida's popular book on Japanese residential architecture (German in 1935, and in English in 1937), applied in a Westernized interior, as we see Frankl would do two decades later. Though actually, Frankl had been using the ichimatsu pattern a decade earlier, in the Kuhrts House, LA (1935) in the year Yoshida's book came out. The enlarged checker pattern was associated with floors or ceilings in the West, or for smaller items as chessboards, or clownish outfits, but not as appropriate for surfacing interior walls, until the Japanese example showed its design potential, for interiors, and from there, at times for exterior facades, as Venturi would do much later.

Thick Repeating Lines

We discussed above the fine repeating lines of Japan with new applications by Frankl. At the other end of the spectrum, is the simple method of repeating thick, bold lines or rectangular bars, with relatively wide spacing as a modern design. While perhaps seeming nothing so innovative, thick lines in the West were not associated with sophisticated design, but more with the stereotypical prison inmates' outfit or the bars which enclosed him, or otherwise those of a gutter grate, as in the humorous cartoon of Adolf Loos contemplating a gridded pattern of a storm drain. The new found profusion of the vertical grid in 20th century Western design was an emancipation from previous associations, thanks to the refreshing use of such patterns in Japanese ukiyo-e, textile patterns, and architectural designs. This was one facet of the technique of the sustained repeating line, both thick and thin (senbonkoshi) which would inspire countless architectural facades in the 20th century.

The Japanese chest shown to the left below is perhaps not the most elegant example of what we have been discussing here; but it is interesting because it references a wheeled vehicle, being called a 'kuruma nagamochi' (車長持ち, 19th century, literally 'long lasting wheeler' or 'sturdy car', the wheels are visible in the photo) while the two pieces shown to the right of it are part of Frankl's 'Station Wagon' line of furniture, evoking the automotive style of the early station wagons. Frankl's furniture does remind us of the early station wagons by Ford; but like the Skyscraper furniture discussed earlier, his designs also have strong parallels to Japanese furniture design.

In other words, whether it be the Skyscraper, Station Wagon, rattan furnishings or his other creations, what runs throughout his work and holds them together, including his pieces that cannot be attributed to one modern industrial icon or another, that are more rustic and organic in nature, is Japanese design.

The Diagonal and Zigzag

A key characteristic of Art Deco was the diagonal and zigzag line, which also is a characteristic of traditional Japanese craft design and painting. Tansu cabinets and a variety of other crafts were exported to the West in the late 19th century with the sort of clear cut lines that would come to be associated with modern design in the 1920's and 30's.

The Japanese Screen as Centerpiece---Striking Asymmetry of the Lustrous Byobu

Frankl often used Japanese byobu as the centerpiece of his living and dining area designs, as the main artwork enlivening an otherwise simple, streamlined interior look. He even at times displays more than one byobu as examples of living interiors, such as in the photo below, center, from his book New Dimensions: The Decorative Arts Today in Words and Pictures (Payson & Clarke, 1928), in which he expounds upon and demonstrates his ideas of what good modern design should be.

Folding byobu screens appear frequently in Frankl's interiors, and the illustration provided below, with screens made by Jean Dunand, has the following caption: "J. Dunand in Paris has revived the ancient Chinese art of lacquer work. The lacquered screens and furniture shown here are characteristic of his work applied in modern furnishings." But this is a rather odd description, since it is a well-documented fact that Dunand learned the craft of screen making and lacquering from the Japanese artist Sugawara Seizo in Paris, as did architect and designer Eileen Gray.*

The art of lacquering in the West was for centuries known as Japanning, having been recognized East and West as the source of the highest quality lacquer; and we should further note, that the oldest existing artefacts of lacquer are scattered throughout the northern half of the main island of Honshu from the middle Jomon Period (third and fourth millennium BC); old as, if not older than the oldest lacquer finds in China. The automatic attribution of things Japanese to China was an adaptive stance in Frankl's day for designers sensitive to popular opinion, where sympathy for China, as Long says, had grown especially after the latter's invasion of the former; but surely this needs now to be corrected.

As can be seen from the photos of the Frankl designed Levine and Wilfley houses (as well as other photos of his interiors), they are predominantly Japanese, or done in the Japanese yamato-e style. It seems Frankl called the screen shown in the Levine House photo a Chinese screen, according to Long, but it is clearly in the Japanese manner, and is likely to be Japanese, while the one on the right in the Wilfley House is unquestionably Japanese, discernable by the painted figures who are in Japanese dress; something that Long probably cannot distinguish (though the white figurine standing on the countertop is probably Chinese).

The simple clean look of the interiors in both recalls the designs of Wells Coates (see article on Coates on this website), such as his remodeling of 1 Kensington Palace Gardens in London, done several years earlier. Coates was a designer who consciously worked to incorporate Japanese aesthetic sensibilities into his designs. Elsewhere Long writes: "Later, in his Los Angeles gallery, Frankl sold patio lounge chairs that seemingly borrowed their forms from the bridges in Chinese gardens." (See photo of the Wilfley House courtyard further below.) But those rounded shapes seem more like the rounded forms of Japanese bridges such as the Kintaikyo of Iwakuni, replicated in so many Japanese ukiyo-e prints circulating in Europe, roundish bridges which, perhaps like Zen and ramen, originated in China, but nevertheless became known in the West thanks to their specific forms developed in Japan.

For clarification, Chinese traditional interiors in the 19th and early 20th century were very different from those in Japan of during those centuries; they were much closer in spirit to that of the West in their rich and bright ornamentation, symmetrical floorplans, construction (often using brick, where walls were weight supporting elements), where ground floors were generally on the same plane as the courtyard, rather than raised up; nor were shoes taken off nor tatami used. Floors of tile, stone, or dirt were common. While there is a great diversity of architectural styles within China if one includes the vast interior, especially to the southwest, a house in Peking or Hong Kong or Shanghai, or any of the major Chinese cities Europeans visited, were quite different from those they visited in Tokyo or Yokohama or Kobe---a fact Western architectural historians seem to have difficulty grasping in their instinctive tendency to attribute things Japanese to China.

The modern, geometric, asymmetric look of Dunand's folding screens, as well as those made by other artists for Frankl, shown earlier, are clearly a trait that evolved in Japanese screen art, not Chinese. Compare the examples of Japanese byobu screens and katagami patterns with bold geometric/asymmetric designs, often conveying a sensation of floating or suspension, shown below, with Dunand's screens in the photo above (center).

A General Kinship between Frankl and Japan in the Conceptualization of Furnishings

Below, to the left, is an omocha-e (おもちゃ絵), or 'toy picture', made for children's amusement and edification. It is a collection of different types of household furnishings of a well-to do household. While similar pictures can be found anywhere in illustrated educational books for children nowadays, nowhere were these pictures so abundantly produced and with such detail as in Japan in the 19th century. Such diagrams were created for almost every conceivable genre of the natural and man made, from plants and animals to hairstyles and combs. These woodblock prints were cheap and readily available to Western visitors to Japan, though no architect or designer mentions them when speaking of the role of Japanese art on their design, whether it be Frankl or Frank Lloyd Wright. Naturally, if they did see such pictures, and gain ideas from them, it would be hard to admit the source of an idea was an illustration made for children. Of course we are not insisting that it was so; traditional Japanese furnishings were in plain sight for Western visitors to see, and there was no necessity to have an set of illustrations on one sheet to derive inspiration from those designs. But we can also imagine that these sorts of pictures, should one come across one in a print shop in Japan, would have been easy to take home, as a convenient encapsulation of Japanese designs, just as Japanese paper architectural models would have been.

To the right is a collage of Frankl's furniture designs put together by this author, an 'Omocha-e of Frankl Furniture' for comparison with Utagawa Yoshiharu's omocha-e of furniture next to it. One to one comparisons might be made, e.g., the side tables in the upper right hand corners of both pictures; but more importantly, are the general shared characteristics of the furniture in both groups of images. Compact rectangular forms with short or no legs, furnishings which hug the ground, or when the legs are longer, simple yet delicate. We see both symmetry and asymmetry. While legged furnishings often have their origins in China, the low heights and legless, boxy look of many Japanese furnishings is a natural result of a tatami-based living style. There are several designs of Frankl's that might seem to have no exact counterparts in Yoshiharu's picture, yet can be found elsewhere in traditional Japanese furniture design, especially that related to the tea ceremony, ikebana flower arrangement, and other furnishing to be placed on the tokonoma. Yoshiharu's yellow, squat and long cabinet, with a Mount Fuji design on its sliding panels, looks just like a modern TV/stereo cabinet of the late 20th century.

Some more comparisons, to indicate the continuity of forms and approach to furniture in Japan from centuries earlier, and the underlying kinship of morphology between Frankl's designs and those of Japan in their combination of simplicity and distinctiveness. The below are not intended to be exact one to one parallels; but the reader should be able to comprehend the continuity with the above examples, and the underlying similarities of furniture conceptualizations between Frankl and Japan.

Though perhaps somewhat difficult to discern, the numbered tables on the left, from top to bottom are: (41) a desk from the Heian period (9th-12th centuries); (40) a reconstruction of a table from the Yayoi Period (c. 400 BC to 250 AD) based on pottery models from that period; (42) a 'yatsu-ashi' i.e., an 'eight legged table' used for religious offerings used during the Heian period; (43) a 26 legged desk preserved in the Shosoin of Nara from the Nara Period (8th century); (44) two dining tables, for individual use at banquets, the one above having octagonal shaped legs, and the one beneath it with openwork boards for legs, from the Heian Period (in Nihon Interia no Rekishi, edited by Koizumi Kazuko, published by Kawade Co., 2015, p. 51). Most of these tables have their precedents in China and were adopted and syncronized over the centuries with the architecture and lifestyles of Japan.

The Japonisme of 'Omni-directional Cubism' in Art Deco and Modernism

The vicarious participation in Japanese space/volumes via readily available ukiyo-e prints, and the actual experience of entering Japanese homes for visitors to Japan, exposed Westerners for the first time to a true fully geometric environment, giving them an isotropic sensation of geometry, unlike anywhere else in the world. Japanese geometric variation and the use of bold line was thorough---on all six surfaces of the interior---i.e. all wall surfaces as well as the floors and ceilings; and continued within storage and furniture spaces and without to the world outside the house, beyond the windows, visible in the highly geometrically ordered facades of surrounding homes and shops.

The adoption of rectangular lighting fixtures looking like those in Japan comprised of simple black lacquered or wood frames, fitted with translucent paper (of varying degrees of thickness or consistency or with visible pulp fragments) was a key aspect of the modern look, though of course wood and paper were substituted for painted metal and frosted or textured glass, a process already at work in Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Frankl's caption for the image to the right is: "French Office. Extreme simplicity of surface with dominating cubist effects are characteristic features of the furniture in this room. The horizontal stripes along the walls are laced together by lines symbolizing mechanical and industrial drawings. The cube lighting fixtures of opaque glass harmonize with the setting. Designed by Georges Lamoussu. Executed by Lincrusta Walton."

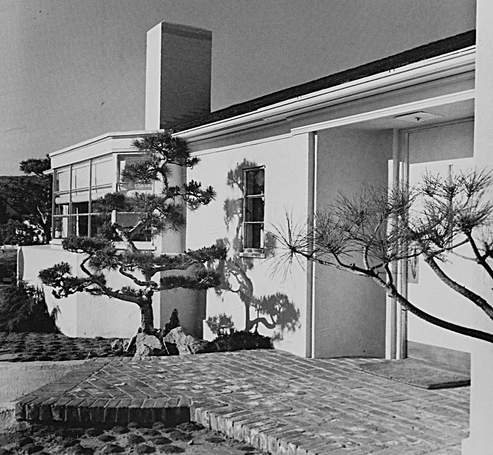

Frankl’s Coldwater Canyon House and some of his other Architectural Projects

"It is hardly a surprise then that when Frankl decided to build his own house in Beverly Hills, he opted for a quasi-Asian “palette.” Frankl, who did not have an American architect’s license, asked Edward Durell Stone to design the house; Frankl would devise the interiors. Stone, who was not licensed in California, in turn worked with local architect Douglas Honnold. The house they created drew directly—or so it seemed—from traditional Japanese farmhouses, notably those with low, hip-and-gable roofs." (Long, 'Asian Influences', 2023) The multiple, irimoya style roofs in the photo below left is one indication of that; the entrance is planted with an irregular walkway and short, horizontally spreading plantings with large gaps between the severely pruned branches, surrounded by irregular rocks and a bumpy array of rounded stones creating what seems to simulate the textural quality of a moss garden.

"Frankl, however, explained that part of the house’s appearance was determined by the site, a long, narrow lot framed on one side by a stand of old walnut trees and on the other by the canyon walls. The rooms were arrayed in a nearly straight line, stair-stepped in two places to accommodate the sharply sloping terrain. An unnamed writer for California Arts and Architecture added that the house was 'conceived in the modern spirit and kept simple and straightforward by the elimination of all things directly not necessary to the mode of life chosen by the owners.' "

This sounds very much like the design of a Kyoto machiya (町家), which also are buit on long narrow strips of land, where rooms are arrayed in a straight line, though usually on flat level ground. The idea of the house being kept simple and straightforward by the elimination of all things directly not necessary" sounds like Frank Lloyd Wright's description of Japanese architecture, what he considered to be the main lesson to be learned from Japanese architecture. Thus it becomes a rather odd non-sequitur for Long to say in his next line that:

"The house was thus, at best, Japanese 'inspired.' The interiors bore this out. Frankl made a lovely interior garden arrangement by one of the stairways, lit from an exterior window. It appears to be much in the spirit of a Japanese formal garden—until one makes the direct comparison. Then the differences emerge. It is too condensed with too many elements. It is rather more an interpretation or an adaptation than an attempt at mimicry."

But there are many kinds of Japanese gardens, and when one of them is built far from Japan, inevitably difference arise, even if there was "an attempt at mimicry." And yes, Frankl has place various Japanese garden elements packed into a small space, but that hardly becomes a denial of fundamental Japanese influence. It appears to this author that Frankl has made a typical 'tsubo-niwa' (literally a 'one tsubo size garden', one tsubo being approximately 3.3 square meters), or an even smaller 'hako-niwa' (literally a 'box garden') meaning in ether case, a minature Japanese garden.

To the right of what we will call 'Frankl's niwa' is a Kyoto tsubo-niwa. It also may be described as "too condensed with too many elements"---for that is precisely the nature of a tsubo-niwa or hako-niwa! And yes, differences do emerge, if one compares gardens like those of Ryoanji with that of a Kyoto machiya tsubo-niwa or a hako-niwa---as when one compares apples to oranges---to refute claims of mimicry. Long has, in other words, forced differences to emerge, when in fact the nature of a Japanese minature garden is one where much is packed into a small space, just as Frankl has done.

Long next says that: "The same may be said for the living room, with its pseudo-Japanese flower arrangements. But they are very nearly inconsequential." But are they? Has he not simply decided for us, that they are inconsequential? Was not the elimination of the inconsequential one of the tenets of Frankl's design? Are not his interiors already sparsely decorated, and thus, do not those flower arrangements, like those in Wells Coates' interiors, provide an important element of psychological comfort and relief?

And how are they pseudo-Japanese, and what then would be considered genuinely Japanese? Frankl is no Ikebana expert, yet he loved Ikebana, and wished to convey the spirit of ikebana---is that not what counts? In the first place, how is Long capable of distinguishing between that which is pseudo-Japanese and that which is the real McCoy? At least from what this author can make of Frankl's interior garden, it is no worse than that of a Japan born amateur's self-made hako-niwa in a crowded metropolis of Japan;---it might be poorly executed, but that is besides the point.

Why, the same accusation of 'pseudo-ness' can be leveled at many European-style interiors in Japan---they are pseudo-European, never purely European, are they not? But that is not the key issue, is it? The European influence is critical in understanding why they are the way they look and why they came to be that way. Denying substantive Western influence, real and vital in understanding Meiji era changes to architecture in Japan, simply because it did not produce an exact replica, falsifies our comprehension of history.

Long eagerly concludes: "The cast of the room is Central European, almost Loosian with its changes in level and the deep, vaguely historically inspired veil of comfort. No one with any familiarity with Japanese design would mistake this space for a traditional house in Kyoto. And any good design historian in Vienna would recognize many, if not almost all, of its features."

While Long has at least admitted the Japanese influence, for which we can give him credit, for better faith than the vast majority of architectural historians, unfortunately he cannot do so gracefully. Obviously, as he says, the house is not the same as a traditional house in Kyoto. And obviously, it is going to incorporate elements of Western comfort. It is not difficult to see this argument of his is a rhetorical strategem: negating significance by denying a perfect equivalence, which is impossible in any case.

And unfortunately one of the things holding back Long's understanding of just how profound the japonisme influence was upon Frankl, is Long's lack of familiarity with Japanese design. He appears somewhat surprised, rather mystified, at how Frankl was so taken with Japan. That is a common reaction among Western art historians (but not artists), who often have stereotypical conceptions of Japanese art as simply derivative of Chinese art, without any appreciation of its singular richness and beauty. Long feels compelled to insist that in the final analysis, after all he has said attesting to Frankl love of Japanese culture, that Frankl's Coldwater Canyon House (implying the case to be so for Frankl's other work), is best thought of in "almost all of its features"---as a product of European civilization. Thus cancelling in effect, any substantive significance to Frankl's pervasive japonisme.

Japonisme: An Understanding of Modern Design where the Dots Connect

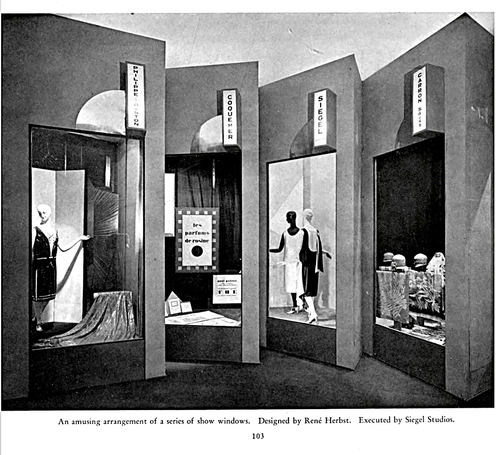

Despite what Long says, just as the Japanese language has come to be often written horizontally, and not only vertically, from the influence of European languages, so too, the reason why avant-garde designers in the West started to create signs with vertical writing is part and parcel of the japonisme influence that saturated their designs. There is nothing inherently more 'modern' about vertical writing than horizontal writing; the fact is---however it might be denied---Japan was broadly associated with the idea of modernism in Europe and America in the early 20th century.

In Japan, the exact opposite happened---the wider adoption of horizontal writing from the Meiji period onward, surely not attributable to indigenous cultural development alone, arose naturally from the strong association with the West of the idea of the modern and progressive. How scholars can easily accept the latter case, but not the former, is a good illustration of just how Eurocentric the world is even now, especially on an intellectual level.

Below are examples of signage by various commercial artists from Frankl's New Dimensions (1928), illustrating what he thought constitutes admirable modern design; and in so many cases, that signage is vertical, reminiscent of signs in Japan and elsewhere in East Asia, but especially in Japan, where very similar signage existed by the Taisho Era (1912-1926) with lettering attached directly to the walls of large buildings or on industrially made panels for shops, and where department stores had expansive, modern display windows.

Stepping back for a moment, surveying the wider horizons of history, the reader is not to be blamed if he finds himself incredulous of the central role of Japan in the birth of what we consider to be the modern world. For in books such as highly acclaimed The Birth of the Modern World, 1780-1914 (Blackwell, 2004), by C. A. Bayly, professor of history at the University of Cambridge, no mention is made of what has been discussed on this website. In his chapter ‘The World of the Arts and the Imagination’, he writes how "African, Asian, and Polynesian motifs and styles invaded European painting, sculpture, and the decorative arts after 1880. For instance, the Anglo-American painter J. M. Whistler spread the fashion for the so-called hawthorn jar which was modeled on the imperial Kanxi blue-and-white style.” (p. 368)

---What an utterly misleading summarization, in a chapter that never (nor anywhere else in the book) mentions even once the word ‘japonisme’, and leads us to believe that Whistler was influenced by China, when anyone with a bit of knowledge about Whistler knows that alongside van Gogh, few have been more clear about their primary Japanese inspiration.

After all, for Bayly, the enrichment of European art from the infusion of foreign elements is nothing but an ‘invasion’, and elsewhere in his work there are phrases which belie what we might call his 'Yellow Peril of the Intellect' views. He does also refer to an invasion of European artistic influence upon the non-Western world; but in that case, as art and architecture was part of the baggage of colonialism, something often directly or indirectly coerced upon foreign peoples, that is not so far from the truth. But the absorption of non-Western art by the West had no aspect of coercion or domination, military or psychological from those countries of origin, and was a purely voluntary assimilation.

Bayly raises the example of Hokusai as fundamentally a product of Western influence. Thus, whether it is a Hokusai or a Frankl, we find ourselves always arriving at the same conclusion in mainstream, well-publicized scholarship: when it comes to interactions with Japan, what counts is the West, "in almost all of its features". Unlike Bayly's treatment of European artists, Hokusai's originality is diluted down as much as possible, his style being one which "blended Japanese and Chinese themes with European romantic styles. Like his contemporaries in science and surgery, he was able to gain access to examples of Western painting through the 'Dutch Learning' diffused from the port of Nagasaki." (p. 382) A description which makes him seem like merely a patient stitcher of Western techniques.

Nevertheless, if that description was balanced with mention of Hokusai's originality and profound contribution to modern artists, it would not be so bad; but he is credited simply as part of a nondescript "European craze for japonaiserie" (p. 382, note not japonisme). Perhaps Bayly should have changed the title of his book to How the West made the Modern World and Others Received it, or something like it more faithful to its content. But in the actual making of the modern world, Japan is irreplaceable. And it is a lovely inheritance to be proud of, no less than the classical; and it is time that historians have the good faith and courage to admit it, without all the hemming and hawing.

*From the Museum exhibit on the japonisme of Art Deco:

アールヌーボーに次いで1920~1930年代に世界で流行したアールデコは、エジプトのデザインや空力形状設計、またはキュビスムを取り入れた様式とされている。が、江戸・明治の日本の工芸や服飾からも、アールデコのルーツを辿ることが 出来る。アールデコの先駆者の一人、高級品工芸デザイナージャン・デュナンJean Dunandは、既に1912年からパリに渡仏していた「幻の巨匠」といわれる菅原精造(Sugawara Seizo)から屏風絵の技法を学び、それを作品に取り入れていた。モードでは、アールデコ時代を代表するマドレーヌ・ヴィオネ Madeleine Vionnetが 日本の服飾の影響を受けたことは研究済みである。また、後にアールデコ 式 グラフィックデザイン の父とも言われる ロシア生まれ の Romain de Tirtoff、通称エルテErtéは、日本の伝統的モチーフやパターン と 酷似する 作品 を多く作り出している。

From Judith Miller, Art Deco: Living with the Art Deco Style (2016, p. 11), on the Japanese influence upon Art Deco:

"The simple geometric forms of Japanese decorative arts and architecture were particularly influential, but most distinctive was the fashion for black-and-red colour combinations, eggshell, and sliver leaf, alongside plain and decorated lacquered furniture, screens, metalwork, and other objects."

________________________

Uploaded 2024.6.20 Under construction

Preview

Richard Neutra (1892-1970)

A Conceptual Japonisme

'Humanized Naturalism', 'Design in Time', and the Multisensory Unity of Architecture and Landscape Design

As a Driver of late 20th and 21st Century Architecture

With References to Kaneji Domoto, Joseph Eichler, Steven Ehrlich, and Christopher Robertson

Yasutaka Aoyama

Richard Neutra's Edgar Kaufmann House ('Desert House'), Colorado Desert, Colorado, 1946. Even the shape of certain individual rocks are homologous to those of famous Japanese temple rock gardens. Photo from Lesley Jackson, Architecture and Interiors from the 1950's (Phaidon, 1994, p. 96-97).

EXCERPT:

Richard Neutra on Japanese gardens (Los Angeles, February, 1959):

"Leaving aside the matter of ritual symbolism, I have always felt the Japanese garden to be a design in time as well as in space. In it, the eternity of shape is kept before our soul by many laborious but rewarding hours of inconspicuous maintenance. In its volumes and in its space relations a twelfth-century garden looks today just as it did hundreds of years ago, although it is composed, not of mummies and relics, but largely of living plants. This is a time cult; it points to the significance time has to life.

Though in different, contrasting ways to this perpetual "still picture" presented by a Japanese garden, the twin-shrine of Ise, one of the holiest centers of Japan's native religion, demonstrates and dramatizes time. There one of the two identical sanctuaries is always under construction, while the other, being used for worship, casts a side glance at its own mirror-image rejuvenation nearby. And once in every generation the intangible godhead of the shrine is transferred from the old to the new building in solemn ritual. After this the old building is demolished and the rebuilding begun again. It is a ritual demonstration, conscious or unconscious, of the never-ending process of decay and renewal that runs through all eternity.

Built and jointed as it is with wonderful neatness and solidity, there is no "practical" need to tear down the shrine. It is not obsolete. It might well stand for a thousand years. Likewise, there is no reason for tending a garden so that through the centuries it will always present, statically, the same compositional ideas. The rationale of what happens both at the Ise Shrine and in the Japanese garden is the same---a symbolic linking of time before the soul of man. fashion does not penetrate here; an uncanny force of primary design, seeming to embody the stability of nature itself, fends off fatigue, neither tiring man nor boring him. ...

Mr. Engels agrees with my long-harbored thoughts. All our sense are used in apprehending a designed setting, be it architecture or landscaping. Even the vestibular sense of the inner ear busily records for us our turns, accelerations, and retardations when, following a magical paving pattern, we haltingly walk the irregular windings of a carefully planned, non-repetitious path or tread the willful zigzag of simple planks bridging a lotus pool.

Thus, a visitor to such a jewel of gardening is kept, with brilliant foresight, tenderly activated by the multi-sensorial appeal of the sounds, odors, and colors of nature, the thermal variations of shade, sunlight, and air movements. Happy endocrine discharges and pleasant associations ply through the visitor's body and mind as he views and promenades. Or, even when he sits seemingly in full repose, that strangely emotive "force of form" that exists in the garden keeps eliciting the vital, vibrating functions of the subtle life processes within him that we call delight. all this is far beyond the effects worked on us by merely quaint, exotic decoration. ...

Japanese towns, villages, houses, and gardens are often miracles of land economy, brought about both out of necessity and from a general sense of thrift. This book gives much more than a glimpse of the "humanized naturalism" of the Japanese landscape, a landscape that proves that even a tightly massed civilization need not spell the defilement of the natural scene but, in fact, can mean its glorification."

From the foreword of Japanese Gardens for Today, by David H. Engel, Tuttle, 1959

To Neutra, Japan provided exalted conceptions of landscape design that had a "unified appeal"; that the Japanese garden was "a profoundly integrated composition" (also from the Foreward, 1959).

Tremaine House, Santa Barbara, 1947

In the same year that the above comments by Neutra were published, so too was Pulitzer prize winner Gary Snyder's popular collection of poems Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems, and we find there analogous conceptions of Japan expressed in poetic form:

A Stone Garden

Japan a great stone garden in the sea.

Echoes of hoes and weeding,

Centuries of leading hill-creeks down

To ditch and pool in fragile knee-deep fields.

Stone-cutter's chisel and a whanging saw,

Leafy sunshine rustling on a man

Chipping a foot-square rough hinoki beam;

I thought I hear an axe chop n the woods

It broke the dream; and woke up dreaming on a train.

It follows with more slips in time forward and back, merging modern and ancient: "It must have been a thousand years ago / In some old mountain sawmill of Japan. / A horde of excess poets and unwed girls / And I that night prowled Tokyo like a bear / Tracking the human future / Of intelligence and despair." This poem, along with others named after temples in Japan, leads to his 'Riprap', for which the collection of poems is named:

Riprap

Lay down these words

Before your mind like rocks.

placed solid, by hands

In choice of place, set

Before the body of the mind

in space and time:

Solidity of bark, leaf, or wall

riprap of things:

Cobble of milky way,

straying planets,

These poems, people,

lost ponies with

Dragging saddles—

and rocky sure-foot trails.

The worlds like an endless

four-dimensional

Game of Go.

It continues with "ants and pebbles / In the thin loam, each rock a word / a creek-washed stone / Granite: ingrained / with torment of fire and weight / Crystal and sediment linked hot / all change, in thoughts, / As well as things."

In Snyder's poem, we see the merging of the American habitat and cultural symbols such as "lost ponies with dragging saddles and rocky sure-footed trails" with that of the Japanese habitat and key cultural symbols in echoes of rock garden vistas---"words before your mind like rocks"; "each rock a word"; of garden-type textures of "riprap", "pebbles", "creek-washed stones"; and conceptualizations of time, matter and eternity echoing Neutra's in an "endless four dimensional game of Go".

This was an era of renewed interest in Japanese culture and art; a 'Japonisme Renaissance' of sorts occurred in the 1950's (discussed in the 'Literary Japonisme' page of this website). A flood of books in English---Japanese literary classics translated by a new generation of translators such as Donald Keene, Edward Seidensticker, and Howard Hibbett, and countless explanatory works on traditional Japanese culture put forth by major Japanese publishers as Kodansha International, or American publishers as Charles Tuttle and Shambhala, were digested by the aesthetically inclined segment of the American intelligentsia. Comparable intellectual interest, in the spiritual to the semiotic, was to be seen in Germany and France as well, exemplified in Oscar Benl and Horst Hammitzsch (eds.) Japanische Geisteswelt (1956) and later in Roland Barthes L'Empire des Signes (1970).

The ideas contained in these books, if in filtered and mixed form, became part of a shared, new aesthetic consciousness---influencing architects and landscape designers---in Europe and America. The interest in Japanese culture, and the desire to emulate it as something avant-garde, can be glimpsed from phenomenon such as the building of lotus ponds to the fad for sitting on zabuton-like floor cushions by the artistic as well as the rich and famous during this period (see photos below from Arthur Drexler and Thomas S. Hines, The architecture of Richard Neutra: from International Style to California modern (New York: MOMA, 1982).

Below are the plan and photos of Neutra's Miller House at Palm Springs, California (in Drexler and Hines, 1982). While at first glance appearing almost industrially modern on the exterior, as the caption reads: "A sliding glass wall and panels of translucent glass contribute to an austere repose reminiscent of a Japanese tea house." In fact there are other aspects of the building and landscape that echo Japanese architecture and landscape design, including the irregular stone garden paths (lower right).

A few more pages from Drexler and Hines's accompanying book to the MOMA exhibition on Neutra. No serious discussion of Neutra is possible without taking into account the various adaptations of Japanese architecture he himself speaks of and are recognized by knowledgeable researchers conducting in depth analyses of his specific works.

A Continuing Tradition of Japan in the Modern Interior-Exterior Conceptualization

Text to be added.

Neutra, of course, was not the only one incorporating Japanese conceptions of space into his work. To the left, a photo from the Lynette Widder (Columbia University) curated 'Kaneji Domoto at Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonia' (June 1017, Feb., 2019) which examined a little known Japanese-American disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright, Kaneji Domoto from the Bay Area, who built multiple projects at Wright's utopian planned 100 acre community of Usonia, a mid-century cooperative in Pleasantville, New York. Domoto "stood out from the other Usonian architects for his strong identification with Japanese traditions, particularly the Japanese landscape" (Claire Voon, 'The Japanese American Architect Who Was a Disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright', August 17, 2017, web-based arts forum Hyperallergic at hyperallergic.com). That much is clear from the photo; Domoto has placed what is a pond, which looks like a rock garden, inside the house, surrounded by shoji panels and a koshi grid overhead, thus in his own unique way, emphasizing the interior-exterior interpenetration by a new combination of elements (Image and caption from 'The Complicated Story Behind the Only Japanese-American Architect at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonia', June 22, 2017, Architectural Digest at architecturaldigest.com). In fact, Domoto's design is a simply a more obvious example of how Japanese architectural elements and conceptions were being integrated into Wrightian modern houses in other places besides the western United States, though without fanfare.

To the right is the walled garden of one of Joseph Eichler's Fairmeadow Tract houses. Eichler, inspired by Neutra and Wright, was a major real estate developer in California in the 1950's and 60's, known for his modernist designs, which, despite being permeated with Japanese architectural features or those analogous to them, are rarely mentioned in that context. Again, Japanese elements are mixed with Western ones in an unusual manner: a minature Ryoanji Temple rock garden is equipped with garden chairs and side tables; various other aspects of the house reflect Japanese architectural aesthetics. Just another indication of how Japanese architecture and landscape design, and the integration of the two, was a key inspirational source in modernist design. (Image: 'Inside a Beautifully Preserved Eichler Home in Orange County, CA' produced by Open Space, at youtube.com)

Text, to be added and photos to be further annotated regarding the Steven Ehrlich and Christopher Robertson houses below.

Text to be added, photos to be further annotated, including a discussion of Gert Wingårdh, in particular his Villa Nilsson in Varberg, Sweden (1996) and its rock garden like interior spaces; and Buff and Hensman's Haptor Residence on Alomar Drive in Sherman Oaks, California (1987). Buff and Hensman worked with Hideo Howard Oshiyama for the garden design and Christopher Cox for general landscaping.

Villa Nilsson photo: Fiona Sinclair; Haptor photo: digs.net.

Further examples include Christina Marham & Rita Qasabian, Markham/Qasabian Residence in Annandale (Sydney), Australia (1992, final renovations 1997), stone garden facing the studio. In Living in Sydney, Taschen, 2001. Photos by Giorgio Possenti, text by Antonella Boisi.

Bibliography (under construction)

Berthier, François. Reading Zen in the Rocks: The Japanese Dry Landscape Garden. Translated and with a Philosophical Essay by Graham Parkes. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2000 (originally in French, 1989).

Drexler, Arthur and Hines, Thomas S. The architecture of Richard Neutra: from International Style to California modern. New York: MOMA, 1982, 1984.

Holborn, Mark. The Ocean in the Sand: Japan: From Landscape to Garden. Boulder, CO: Shambhala, 1978.

Suzuki Daisetsu. Zen and Japanese Culture. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1959 (originally Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture, 1938).

Tamada Hiroyuki. 'Richard Neutra's Architectural Thought and Japan'. Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ), 2006, Vol. 71, Issue 600, pp. 223-228.

Watts, Alan. The Way of Zen. New York: Pantheon Books, 1957. (Watts' book follows that of Suzuki Daisetsu in terms of substantive content.)

________________________

Uploaded 2023.7.18. Under construction, photos to be annotated

Preview

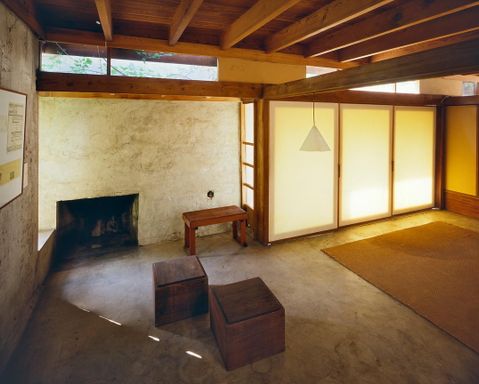

Rudolph Schindler (1887-1953)

The Schindler/Chace House, 1922

Recreating Japan for his Own Home

Yasutaka Aoyama

"Upon arriving at the dwelling that the architect and his wife Pauline built in 1922 on Kings Road, visitors discover the house concealed by towering hedges; and only upon coursing the 200-foot driveway does the low-slung Japanese-esque residence reveal itself modestly." ---Western Art and Architecture, David Masello, 'Perspective: The 100-Year-old Radical', October/November 2023 (https://westernartandarchitecture.com)

"Both the style and construction of the house were completely novel. The floors, for example, are bare concrete. The walls, too, are concrete, with unadorned slabs separated by tiny strips of opaque glass rather than windows. To balance the industrial chill of cement, redwood framing of roofs and windows provides natural warmth. The effect is strongly reminiscent of traditional Japanese architecture, with its simple, modular plans and rustic elegance." ---Metropolis Magazine, Robert Landon, 'The Schindler House Was the Source Material for Californian Architecture: From utopian communal living to pioneering the modern American dwelling'. September 7, 2013 (https://metropolismag.com)

"In our opinion, Schindler realized the potential of Japanese architecture in the contemporary scene and made a very intelligent effort to revitalize traditional concepts." José Manuel Almodóvar Melendo, Juan Ramón Jiménez Verdejo, and Ismael Dominguez Sánchez de la Blanca, 'Similarities Between R.M. Schindler House and Descriptions of Traditional Japanese Architecture,' Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 48, January 2014.

The photographs of the Schindler House that most often appear in architectural books and websites do not show the most Japanesque elements of Schindler's designs. But even then, one can make out the koshi (格子)-like grid windows, some with plain off white curtains behind them; others without curtains, contrasted with plain, rustic, textured walls; the chromatics of subdued browns, whites, and greys; the hedge, suggestive of ikegaki (生垣); also bamboo clusters; vines hanging from fujidana (藤棚)-like trellis-eaves; other garden plantings looking like neko-jirashi or susuki or other ineka (稲科), i.e., rice-grass type plants; stone steps in the garden placed in a Japaneese checkerboard style--all this, and much more, evoking a secluded, traditional Japanese residence.

José Manuel Almodóvar Melendo, et al., in their “Similarities Between R.M. Schindler House and Descriptions of Traditional Japanese Architecture,” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 48 (January 2014), provide the best analysis available on the close connection between the Schindler House and Japanese architecture. Otherwise, Landon, Masello, along with the noted architectural historian James Steele, and Christopher Long (the biographer of Schindler's contemporary, the designer Paul Frankl), are among the few writers who have been frank about the obvious Japanese influence on the Schindler House. Here we will look at aspects not touched upon by the above writers. A reading of Almodóvar Melendo, et al. (2014), in tandem with this paper, is highly recommended.

Landon notes that "Schindler’s radical innovations have all become such commonplaces of California architecture: open floor plan, flat roof, sliding glass doors, seamless movement from the house to a garden that turns its back to the street." All these, except the flat roof, are key lessons taken from Japanese architecture. Even the glass sliding doors, which had been in use since the 1860's in Japan, and were commonplace by the first decade of the 20th century. But in the early 1920's, in California, as Landon says, "all these things were considered so bizarre that the local planning authorities denied permission to build. Eventually a temporary permit was granted, reserving the right to halt construction at any phase."

The Schindler House is included in most surveys of modern architecture, precisely because it was highly unusual for its time, and after fellow Austrian-born Richard Neutra, it is Schindler who is often raised as one of the leading pioneers of the more truly modernist or international style of residential architecture in America. It goes without mention that Frank Lloyd Wright was a pivotal figure in modern architecture, who both of them worked for---but Wright incorporated the Japanese element of heavy roofs with extending eaves, and did not consider himself a 'modernist' of the same kind.

Regarding the Schindler House, William Curtis, in his now standard reading for college and graduate school architectural history courses, Modern Architecture Since 1900 (going through various editions and reprints), brings up "the architect's interest in the Indian pueblos" (p. 232, 3rd Edition, 1996) due to some of the walls being reminiscent of those of the sloping adobe. Only a page later does he say that, "The interiors were probably indebted to Japanese architecture, especially the contrived incompleteness of the teahouse." (p. 233), leaving us with an impression that the Japanese influence was only probable, and somehow lacking in naturalness and completeness. That is the extent of Curtis' comments regarding the Schindler house in relation to Japanese architecture. But perhaps it might be said that it is Curtis' words that are somewhat contrived in their incompleteness of description; for not only the interior, but the exterior, the plans, and for that matter, the entire conception of the house, is indebted to Japanese architecture.

Curtis's following comments are: "The movable wooden screens (which were initially of canvas and only later of glass) were inspired by a temporary camp in which Schindler and his wife stayed while the house was being designed." (p. 233) This is a little too ingenuous on Curtis' part; how much more reasonable to say that these too, were inspired by the most fundamental of Japanese architectural features, that is sliding screens, of which we have discussed in more than enough length elsewhere on this website. The give away is the fact they were initially sheeted with canvas, thus approximating the effect of papered shoji or fusuma, but without needing the Japanese washi paper or cloth to fabricate it or having to maintain it---in another case of the classic japonisme technique of material substitution.

Furthermore, Curtis says: "The eye was kept down by a continuous horizontal transome above which there was a clerestory" (p. 233). This too, reflects Japanese architectural design, in its low, narrow, and horizontal emphasis, i.e., the ranma, of the kind shown below of the Yoshino Farmhouse of the early to mid-19th century. Yet we cannot be too harsh only on him; Curtis is not alone in this sort of descriptive lapse. Almost all introductory texts to modern architecture, as well as monographs on Schindler, excepting again that of Steele, omit the Japanese influence, or make only the slightest passing references to it. Take for instance, August Sarnitz's R. M. Schindler, Architect 1887-1953: A Pupil of Otto Wagner, Between International Style and Space Architecture (Rizzoli, 1988); or David Gebhard's Schindler (Thames and Hudson, 1971); or Robert Sweeney in The Architecture of R.M. Schindler (organized by E. A. T. Smith and M. Darling, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 2001); or Judith Sheine's R. M. Schindler (Editorial Gustavo Gili, 1998); or Kathryn Smith's Schindler House (Harry N. Abrams, 2001); as well as Peter Noever (ed.), MAK Center for Art and Architecture: R. M. Schindler (Prestel, 1995)---no mention of Japanese architecture regarding the Schindler House in any of these, or for that matter, anywhere in those books (except in relation to Schindler's handling of Wright's work during the latter's trips to Japan), though there are references to other influences such as 'Pre-columbian' architecture, besides the 'Indian pueblos'.

That being the case even if the circumstantial evidence of Japan is everywhere to be found, in the architecture itself and the events and people surrounding it. Starting with before his building of the house, Schindler works with Japanese architects/draftsmen at Wright's Taliesin, such as Arata Endo and Goichi Fujikura; Taliesin of which he was a great admirer of, much influenced in design by Japanese architecture (Kevin Nute, 1993), is filled with Wright's Japanese architectural models and art objects, which can be seen in photos Schindler himself has taken (Smith, 2001, various photos). There, Schindler worked on the Tokyo Imperial Hotel project, and thus was constantly involved with Japan, and unavoidably exposed to issues of Japanese architectural and constructional practices. This fact, that he worked on the Imperial Hotel project, is often glazed over in the above mentioned books on Schindler, which often simply say he was taking care of business in the US while Wright was away in Japan.

Later in 1923, shortly after the Schindler House is built, Wright brings back young architects from Japan, who become live-in guests at the Schindler House, including Kameki and Nobu Tsuchiura (Smith, 2001, p. 26). The manner of living in the house, the sparse, low set furnishings, the sitting on the floor, not just the Schindlers, but also the Chaces, Marian and her friends (see the photos below) also echoes Japanese culture. And not only the Neutras, but the circle of artistic friends that the Schindlers invited to the house, including the photographer Edward Weston (exhibit at the Japonisme Museum), the composer John Cage (has a composition 'Haiku' and known to have an interest in Japan), and the author Theodore Dreiser (details as in his Titan, comparing Sohlberg with Japanese prints), for instance, reflect Japanese aesthetics in one way or the other in their work. And no other cultural theme, whether Native North American, Pre-columbian Central American, or otherwise, can be found in its design with such consistency, when it comes to the Schindler House.

More recently, one California design firm, Rost Architects, at least includes Japanese design among several factors in the making of the Schindler House: "The home shows a synthesis of Frank Lloyd Wright, paired back European modernism, Japanese domestic design, and the optimization for the Southern California climate, perfectly balanced into a single work of architecture." ('Six Things You Should Know About Southern Californian Architect Rudolph Schindler' Nov. 23, 2022, at rostarchitects.com) But it should be noted that those other influences, the Wrightian elements, the European modernism, and even the search for an architectural style suitable to the Californian climate (see C. Lancaster, 1963) also evolved hand-in-hand with a conscious adaptation of Japanese design principles. Thus whether directly or indirectly, all these factors are connected to Japanese design. Even Schindler's use of concrete, it could be argued, though seemingly unrelated to Japanese traditional architecture, is used in a way that evokes a 'shibui'-type of down to earth textures and chromatics, found in tsuchi-kabe / shikkui walls (explained below), or carbonized wood surface finishings and the like (example at the end).

The parallels with Japanese architecture become more apparent when one gets to know Schindler's ideas about design and construction in more detail, such as outlined in his 'The Schindler Frame' (Architectural Record 1947) which can be summarized in seven points, for which we will quote Sheine (1998), adding comments on their similarity to Japanese architecture: 1. Large openings in walls [in Japan there are minimal walls, sometimes none at all, or walls that are peforated, or exist with a section missing such as the sode-kabe]; 2. Varying ceiling heights [in Japan ceiling heights can vary substantially, e.g., from the doma area to the zashiki living area]; 3) Low horizontal datum [as in Japanese houses where the visual perspective is often from a sitting position on the floor]; 4) Clerestory windows [i.e. ranma and gridded windows of the kind shown below in the Yoshida house]; 5) Large overhangs [i.e. extensive noki eaves as in Japan]; 6) Interior floor close to exterior ground [as in a Japanese house]; 7) Continuity between adjoining 'space units' [as in Japanese houses where sliding screens can be opened or removed to create fewer or even one contiguous space at will].

We can add Schindler's cutting of all studs throughout the house to door height, creating horizontal continuity, as also analogous to the system of Japanese framing matching the height of sliding screens (fusuma or shoji), from which thereon upward, the height of the ceilings can be varied with ranma, angled ceilings, or no ceiling with exposed intersecting beams above.

As Christopher Long, an authority on the designer Paul Frankl, guesses, "Somewhere along the path of his early career, he had seen enough of traditional Japanese building to borrow from it and transform it in his own way."

Long continues: "I emphasize this because Schindler’s Kings Road House, one of the most manifestly Japanese of the Asian-inspired houses of the early Los Angeles moderns, was no mere replica. As Almodóvar and his co-authors note, Schindler implemented a composite construction system. Their claim is that it is “clearly similar to that described by Morse [Edward Morse] but, of course, that does not necessarily mean that Morse was Schindler’s source."

Indeed, books, photographs, ukiyo-e prints, American architectural journals, postcards featuring Japanese architecture were available and more plentiful in the United States by the early 20th century. There existed easily obtainable do-it-yourself cut out paper architectural models, as those shown below, with the kind of architectural features found in the Schindler House. There was no need for Schindler or any architect in America or Europe to rely on the 19th century works of Morse, Cram, or the better known writers of 19th century architecture in Japan. More specifically, as Long relates:

"What one does see throughout the house is how Schindler adapted traditional Japanese woodwork to simpler joinery—mostly nails—and standard, industrially produced milled lumber. What is also evident is the way in which he opts for an open framing system, with spatial partitions arranged in such a manner that they are not load bearing—in keeping with Japanese tradition. In an article he published more than a decade later in T-Square, Schindler describes his approach: 'all partitions and patio walls are non-supporting screens composed of a wooden skeleton filled in with glass or with removable canvas panels.' " ('Asian Influences and the Rise of Southern California Modernism', Nonsite.org, Issue 43, June 16, 2023; at nonsite.org)

This is of course synonymous in meaning with the construction principles of Japanese architecture, with minor modifications, such as the use of canvas instead of paper, cloth, and/or wood.

These inexpensive Japanese paper models, called 'kiritourou', which might be translated as 'house lanterns' lighted with candles from the back side, were simple architectural models that clearly exhibited architectonic principles found in the Schindler House. Note, for instance, the similarity of the gridded and blank screens of the living spaces, opening up to the outside (above left and right), or the narrow, long windows above the screen doors in the sheet above right by Utagawa Toyohisa, or the clear sectionalization of exterior walls below in any of the Kuninaga sheets; and the basic idea, though the specific layout might differ in this case, of a winding floor plan (shown below in axonometric within the far righ sheet), with separated rooms and separated semi-enclosed gardens, as in the Schindler House.

Utagawa Kuninaga (歌川国長), Kirikumi Tourou 'Aki-no-Miyajima', between 1804-30, Ann Herring Collection

From Edo no Omocha-e (江戸のおもちゃ絵) Part 2, edited and published by the Tabacco & Salt Museum, 2023.

A Japanese style free floor plan

Attach a sloping Japanese roof to the isometric (right), and it becomes virtually indistinguishable from a Japanese traditional house.

Japanesque Interiors

Text to be added.

Points to be discussed include:

Sliding panels similar to shoji and fusama; narrow windows above like ranma; outlined wall panels reminiscent of country houses with shikkui (漆喰) plaster or tsuchi-kabe (土壁) earthern walls, in the sandy or classic light mustard color, 'odo-iro' (黄土色), found throughout Japan. Note in the Yoshino farmhouse sliding exterior screens, how the grid is relatively widely spaced, which was common in Japan soon after the use of glass, which allowed it, versus paper (which required more support and thus a more closer spaced grid) the wider spacings. The characteristics of the modern are to be found in Japan before the West, even in such details.

"Schindler developed ways to make inexpensive modern architecture out of cheap materials—stucco and plaster over wood frame—in what he called his “plaster skin” designs of the 1930s and early 1940s; notable examples include the Oliver (1933–34), Walker (1935) and Wilson (1935–39) houses." (MAK website) Schindler's plaster skin is analogous in conception to the above mentioned 'tsuchi-kabe' (土壁, literally dirt walls) or 'shikkui' (漆喰 Japanese plaster) walls done over wood frames, and even in the concrete walls of the Schindler House, we can see visual and textural echoes of Japan.

His shelves visible (below, center) are reminiscent of chigaidana. The door is a fusuma resembling type door like those in Japan in the Meiji and Taisho periods when doors were adopted and harmonized with traditional Japanese interiors.

The low, box-like furnishings also echo Japanese furniture forms. Even Schindler's simple, small lighting fixtures are similar to the kind of hanging lamps being used in Japan, only that he has hung them reaching much lower, in tune with Western tastes.

Below, left: Private dining room of the emperor at the Nishifuzokutei, one of the imperial estates located in Numazu, Shizuoka. Compare it with both the Schindler House images immediately above and to the right of it. Almost all Japanese city residences of the middle class, not only the wealthy and aristocratic, had glass inserted into traditional type sliding screen frames by the early 20th century, which of course could be slid open to create an integrated space with an inner garden as in the Schindler House. In the Nishifuzokutei (西付属邸), the glass inserted screens are of the 'koshitsuki' (腰付 'waist-attached') type, that is with a board of wood running along the bottom (often taller than needed for better structural strength), which Schindler follows.

The furnishings in the imperial estate are along the lines of the traditional European, this being the turn of the century style in Japan among the wealthy and aristocratic; but once again show how design in Japan, by the merging of Western elements with the Japanese, was naturally evolving in the direction of what would be considered modernist in the West, ahead of America and Europe.

Japanese Contrastive Aesthetics: The House vs. Kura

Another characteristic of Japanese architecture that Schindler has adapted is the contrasting effect of the Japanese storehouse / treasure house called the kura (蔵), an extremely thick walled, plastered, box-like structure, often in a plain whitish or greyish color (with usually one, or perhaps two small windows and a double doored entrance). It is often situated across the garden from the residential structure, though within the wall enclosure of the yard, visible from the house, sometimes adjacent and attached to it as in the picture below, left. Given that traditional Japanese houses are extremely airy, light, and asymmetrically built, the kura, which in many ways may be called its architectonic antithesis, creates a very impressionable contrast. Here, as we will see elsewhere, Schindler has expressed a Japanese architectural aesthetic, but applied it to something of different function using different material, than is in Japan---i.e., from a storehouse to a chimney.

Further examples of Japanese kura, these from Shimane prefecture, from Masuda Tadashi, Kabe Mado Koushi (Tokyo: Gurafikku-sha, 1997).