If the images do not appear in due time, please refresh/reload the page.

Architectural Japonisme V

建築のジャポニスム V

1. Origamic and Origami Architecture

The Unleashing of Imaginative Freedom within Geometric Order

With References to Chatani Masahiro, Santiago Calatrava, Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry, Elon Musk, and Others

2. Towards a Better Understanding of Architectural Evolution

'Inevitable' Transformations of Traditional Japanese Design into Modernist Architecture

3. Frank Lloyd Wright, Excerpts from his An Autobiography

With Commentary and Annotations (to be added)

4. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Japonisme of the Kitchen 'Workspace'

Open Floorplan Kitchens and Kitchen Islands

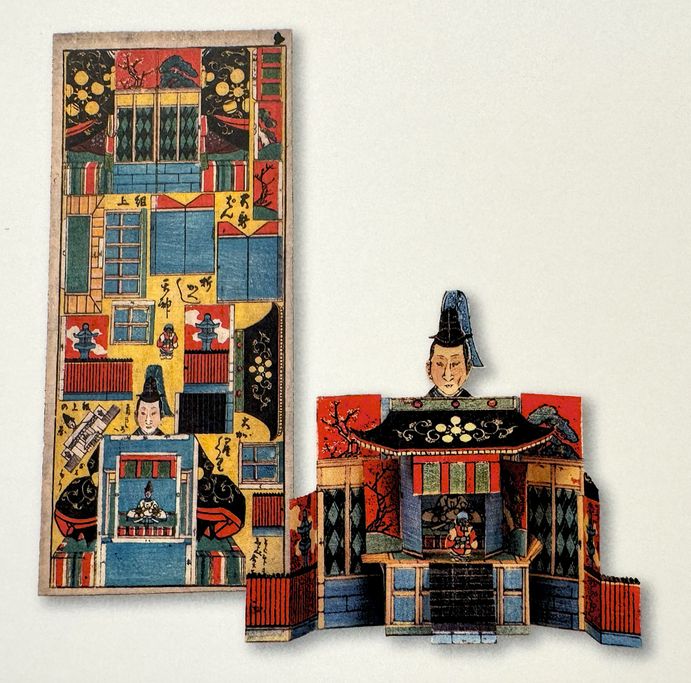

Image from a cover of one of Masahiro Chatani's books on Origamic Architecture.

Uploaded 2024.7.14. Under construction, text to be revised and photos to be added and annotated

DRAFT

Origamic and Origami Architecture

The Unleashing of Imaginative Freedom within Geometric Order

With References to Masahiro Chatani, Santiago Calatrava, Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry, Elon Musk

Yasutaka Aoyama

Origami is a traditional Japanese art form and recreational activity, practiced at least from the early 17th century, ‘ori’ meaning ‘folding’ and 'gami' meaning ‘paper’. ‘Origamic architecture’ refers to the art of cutting and folding paper to create three-dimensional scale models of architectural forms, in contrast to ‘origami architecture’, the recent design principle utilizing the Japanese art of origami.

Paper and Folding

Origami is the intersection of two particularly rich traditions of Japan---

1) Washi paper (和紙) manufacturing, the crafting of innumerable types of Japanese handmade paper, an art form in itself, unmatched in the world in terms of quality and diversity; and

2) Folding (折り), in all its myriad forms, expressed with unrivalled sophistication not only in paper, but in cloth and wood, and combinations of paper, wood, and cloth. From folding fans to folding umbrellas to chochin lanterns, on to modern time triangular folding of toilet paper at hotels (see footnote) and department store virtuoso gift wrapping---folding---once deeply part of the culture, was so widespread and habitual that it was criticized in the recent past as unecological ‘overpackaging’.

In any case, we must never forget that origami is but one of many highly developed artistic combinations of the culture of Paper and Folding in Japan.

Origami and Kirigami

Origami may be considered part of a wider category of paper arts using Japanese paper, or chiyogami (千代紙), which includes not only foldings but also kirigami (切り紙), the art of paper-cutting. Strictly speaking, origami is the art of paper folding, while kirigami is the art of paper cutting in combination with folding techniques. Additionally, we might add, though not yet used in architecture (though probably to be utilized one day, this author predicts), is ‘chigirigami (ちぎり紙), the art of making pictures by tearing paper and pasting those torn pieces to a larger sheet of paper.

Origamic and Origami Architecture

For further clarification, in lower majuscule, origamic architecture will refers to the former, especially that of Chatani Masahiro (茶谷正洋 1934-2008), at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, and his ideas and examples he produced, from which a good part of the inspiration for origami architecture has arisen. However, the term ‘origamic’ as an adjective will also be used to refer to ‘origami-like’ qualities, or arising therefrom, whether or not precisely origami itself. When capitalized, the term ‘Origamic Architecture Movement’ will be used to refer to the architectural movement that arose in the late 1980’s and continues to the present in great force, stimulated by origamic architecture. The term ‘origami architecture’ will be used generically, to describe any architecture that is derived from origami modeling or clearly inspired by origami, whether it be from the early 20th or 21st century. Thus, in many cases, the two terms, origami architecture and orgamic architecture, will overlap substantially in meaning, seeming synonymous, though strictly speaking, distinguishable. For the proper perspective, we should add that Japan has a long tradition of both cut-out and pop-up paper architecture as games and toys from the early 19th century, in the 'omocha-e' (おもちゃ絵), and as folded and cut paper 'okoshi-e' (起こし絵) models for tea houses, from the 17th century.

The Origins of Origami

Before proceeding with a discussion of origami and architecture, it is important to set the record straight regarding the origins of origami. There is a widely disseminated assertion, with neither historical nor archaeological evidence, circumstantial nor direct, of any kind, that with the invention of paper in China, by extension, origami was invented there shortly afterwards. The word that is often raised is ‘zheshi’, which is simply the Chinese pronunciation of the characters for origami, probably a recent adaptation of the term, and most likely starting as a transliteration of the Japanese. Books on Chinese folding paper appeared clearly after the interest in Japanese origami in the West, one of the earliest being Mary Soong’s The Art of Chinese Paper Folding for Young and Old (1948), which depicts an origami crane on its title page, a fold with much earlier precedents in Japan.

As Hatori Koshiro observes in his chapter for the proceedings of the Fifth International Meeting of Origami Science, Mathematics, and Education, Origami 5, the claim of Chinese origins may have become more widely spread when Lillian Oppenheimer inserted the notion in her foreword for Isao Honda’s book How to Make Origami (1959) by saying:

"Like tea and gunpowder, paper was introduced to Western civilization from the East; the Chinese invented it 18 centuries ago. Also from China and Japan came a form of art in paper, Origami (literally 'folding paper'). Origami has been known to the Chinese and Japanese about as long as paper itself."

However, as far as this author can ascertain, there is no written reference to (besides the two characters in combination simply referring to the folding of paper in general), to any kind of origami as a conception of art or pastime in ancient China. Anyone who scrutinizes Oppenheimer's reasoning will see that she has simply used the technique of verbal juxtaposition and 'argument by association'---starting with a widely accepted major premise of paper and China, then China and Japan as both part of the East, and from that a syllogistic leap of China to origami.

However, it was not the invention of paper itself---any more than the invention of gunpowder implies the invention of a breech-loading rifle or tea drinking automatically leads to the development of a tea ceremony as a complex art form---that was the key to the development of origami. Rather, it was the ingenuity of those anonymous craftsmen in Japan who developed a thin yet taut paper, a form of Japanese paper, of 'washi', that was the first technical requirement towards an art of paper folding. That is to say, it was the development of 'multi-foldable shape-maintaining' paper' or what we will call here ‘Ori-washi-gami’, that paved the way for the development of paper folding as an art. As Hagiwara Ichiro, Meiji University Distinguished Professor Emeritus for the Advanced Study of Mathematical Sciences, points out:

"Japanese created the world’s first foldable paper using tenacious elm. Subsequently, it was discovered that washi became more rigid and produced a beautiful lustre when folded." (‘Origami Engineering: inspired by Japanese folding culture Kirigami and fan folds represent new opportunities' by Ichiro Hagiwara and Akiko Kondo).

While Hatori speculates that prehistoric paper made from bark may have been of a kind amenable to folding in Southeast Asia or Oceania, this in itself does not mean origami might have been practiced there. In general, ancient paper, whether made of papyrus or other wood fibers, was either too brittle or too soft for repeated folding into the kind of sophisticated and delicate constructions conducive to the development of an art form. Furthermore, the paper with the right constructional quality had to be produced in good surplus quantity, beyond the primary requirements of writing and religious ritual needs, to become a pastime as well as an art, which too occurred relatively early on compared to the rest of the world, by the 18th century.

Hatori's chapter, the first of the conference, and thus designated special weight, concludes will the following paragraph:

"In the first years of the Meiji Restoration, in the 1860s and 1870s, the European education system was introduced and adopted in Japan. As a result, European origami was imported to Japan as a part of the kindergarten curriculum. In addition, as people traveled internationally, Japanese origami spread over the Western world. The state of origami as we know it today has been developed as a consequence of such a cultural exchange. Thus, origami has never been a 'Japanese' art."

Here Hatori may have scored points of approval from a certain segment of his audience; yet if we think carefully about it, his conclusion is a spectacular non-sequitur. His argument that, because there are differences in simplistic folding practices in the West from that of Japan, and because Froebelian paper-folding---after origami had already blossomed in Edo period Japan into what we consider an art form today---was adopted into the Westernized Japanese curriculum in the following Meiji period, or furthermore, because people travelled internationally spreading Japanese origami, all or any of the above does not lead to the conclusion: origami has never been a Japanese art. It only proves that folding paper practices were never a Japanese monopoly; while origami as we know it, as a wide spread pastime and art form, was indeed 'Japanese', and would never have become the phenomenon it is, were it not for Japan. Or stated alternatively, Japan is both the necessary and sufficient cause of modern origami, while none of the other sources are sufficient or necessary for the birth, development, and spread of origami art, and perhaps it is not without reason that we call it 'Origami', and not 'Froebelian Folding' or 'Zheshi'.

Buddhist and Shinto Paper Folding Culture

Copying sutras and records was an important use of paper, which of course was often done on long, folded joined sheets of paper. This however, is hardly sufficient as an originating cause of origami, though it should be mentioned as one element of many contributing to a general culture of folding that was developing in Japan over the centuries.

What is more important is that paper came to be used for Shinto rituals, for the purifying waving wands called 'oonusa' (大麻) with zigzag folded paper 'shide' (紙垂) tied to it, as well as for wrapping offerings to the gods, where precisely determined ritual folds were developed and are depicted in medieval picture scrolls as the 14th century Fudo-riyaku-engi-emaki (不動利益縁起絵巻), for instance, shown below.

‘Noshi’ (熨斗), the ceremonial decoration for offerings, in particular the noshi-awabi (熨斗鮑), the wrapped offering of a sun dried stripe of abalone, is mentioned even in the 8th century Nihonshoki, though evidence that it existed wrapped in the kind of complex origamic folded paper we know today, is recorded for instance, in Ise Sadatake (伊勢貞丈)’s Teijozakki (貞丈雑記 1763-1784 ), a comprehensive book of samurai customs and etiquette, where it clearly describes the noshi as a complex folded paper wrapped offering. We should note another origamic practice, the making of folded paper models representing a male silkworm/butterfly, 'ocho' (雄蝶) and a female silkworm/butterfly 'mecho' (雌蝶), were attached to two sake decanters called choshi (銚子) during weddings conducted at home, common certainly by the early Edo period, and standard practice to this day in Shinto wedding ceremonies.

According to the Hiden Senbazuru Orikata (秘伝千羽鶴折形, 1797, which will be discussed below), in English translated with a flourish as The Secret Legend of a Thousand Cranes, it was Gido (義道 going by literary moniker of Rokoan 魯縞庵 c.1759-1834), 11th abbot of the Jodo Shinshu Sect Choenji Temple (長円寺) in Kuwana, in present-day Mie Prefecture, who was the inventor of the 'renzuru', or folded, linked multi-crane origami, which it is said, took him 18 years to derive. Gido is believed to have devised not only the renzuru, but other origami; unfortunately, none of his other folds have survived.

Gido is one of those unsung cultural heroes, a noted man of cultivation in his own time, who not only invented the Renzuru, but was a versatile poet and investigator of historical sites, and author of various learned books of which several remain (see the Kuwana City website, bunka.city.kuwana.mie.jp). He was friends with Confucian scholars of the Kuwana and Nagashima domains, and is said to have presented his crane creations to feudal lords of those regions. His contacts reached far and wide, being acquainted with the versatile scholar, artist, art connoisseur, and herbalist, Kimura Kenkado (木村蒹葭堂) of Osaka and the erudite compiler of the Tokaido Meisho-zue, Akisato Rito (秋里 籬島) of Kyoto, who came to edit Gido's Hiden Senbazuru Orikata, often referred to as just the Senbazuru Orikata (tamagawa.ac.jp/museum/archive). We might note for interest that Gido’s folding method was designated as an intangible cultural property of Kuwana City in 1976, and named the "Kuwana Thousand Cranes".

Samurai Paper Folding Culture

From the 15th century, origata, a method of folding gifts and letters in paper, developed as etiquette among the samurai class, though a prototype to it was probably part of aristocratic upbringing much earlier. Thus, along with a culture of paper folding developing in religious contexts, a parallel growth of paper folding practices among the ruling classes, mutually reinforcing and intersecting with those of the religious kind, arose as an important precursor to origami, becoming a vital skill of protocol for the ruling class in Edo period Japan. This became quite a complicated affair where the rules of complex folding were set according to the occasion, status, and content of that which was wrapped. We should add here that the development of the tea ceremony, popular among the samurai class but also with a following among the merchant class, had a tradition of folding from the 16th century, not limited to paper, but applied to the manner of folding cloths as well. Etiquette became a true art form in Japan, where certain schools of etiquette, notably the Ogasawara, Ise, and Kira became renown, from which other samurai clans eagerly received instruction, all with their subtle variations in folding practices, whether of paper or cloth. This was considered part of the proper upbringing and cultivation of women as well, or perhaps particularly so, as the Onna Chohoki or Women's Treasury (女重宝記 1692) by Namura Johaku (苗村丈伯) for instance, one in line of texts on the training of ladies, included many illustrations of proper folding techniques similar or analogous to those used in origami, such as in his fifth volume with Ogasawara style foldings. These of course were summaries of what were considered reputable, well-established folding practices, and a good amount of it certainly predates the book by at least decades, if not much longer.

Different wrapping folds in the Onna Chohoki, 1692

More wrapping folds from the Onna Chohoki, 1692

According to the aforementioned Ise Sadatake, of a reputable samurai family, who wrote a book of ceremonial origami Tsutsumi-no-ki in 1764, such paper folding was established in the Muromachi period (1333–1573). Often the oldest origami book is considered to be the Senbazuru Orikata, but the Tsutsumi-no-ki perhaps better deserves that title, since it does include 13 folding patterns in it which can be considered origami.

We should add that folding in general among samurai, especially of clothing was a very precise skill; each vestment had its way of being folded properly and, indeed, much of samurai clothing had a paper-like quality, starched and stiffened so as to maintain angular shapes, such as the kataginu (肩衣) and hakama (袴)comprising the kamishimo (裃), and, though not starched, the obi (帯) worn by women, for example. Paintings of courtiers and aristocratic women, and poets from even Heian times were often drawn in a way reminiscent of cubist depictions.

Captions to be added.

From these paintings it can be seen that clothing was depicted much like folded paper. Regardless of whether origami as an independent art form existed in Heian times, a culture of folding and an aesthetic appreciation of the fold, that is to say the workings of we will call origamic perception can be observed, already by the 12th century, something quite unlike anything found in China or the West or elsewhere in the world.

Popular Paper Folding Culture and the First Origami as we know it Today

In his Life of an Amorous Man (Koshoku Ichidai Otoko 好色一代男, 1682) the novelist Ihara Saikaku (井原西鶴) made casual poetic references to crane origami, giving some indication of how commonplace paper folding as a pastime had become by then. The 17th century was a period of increasing paper production in Japan, which came to be mass-produced and thus obtainable at low cost, which was probably an instrumental factor in allowing the spread of origami as a pastime of the general public. In 1797, the Hiden Senbazuru Orikata, or the The Secret Legend of a Thousand Cranes, which some consider the world's oldest first true book on origami, edited by Akisato Rito, mentioned earlier, was published. Already however, books, ukiyo-e prints, kimono patterns, and the like, frequently depicted origami forms. Nishikawa Sukenobu (西川祐信), Isoda Koryusai (磯田湖龍斎), and other ukiyo-e artists of the early and mid-18th century produced illustrations of women engaged in origami folding, and the diversity of folds can be gleaned from a variety of images such as the ranma design shown below.

Ranma Zushiki (欄間図式), 1734

European Folding Paper Traditions

Much has been made of German educator Friedrich Froebel (1782 - 1852), inventor of the kindergarten (whose conceptions are not without parallels to those of the widespread terakoya temple schools of Edo period Japan), who was also a proponent of paper folding and its educational benefits. Perhaps one of the reasons origami was practiced by Buddhist priests in the Edo period, a tradition continuing into the 20th century, was because it was originally taught to young children at the terakoya---something that needs verification---an interesting topic for future research. In Japan one hears of how Froebelian paper folding was introduced into Japanese schools in 1880. Yet to be investigated, however, is the possibility that Froebel was familiar with the writings of von Siebold or had access to other information on Japan. Unlike the stereotypical image of Japan being a closed country before the mid-19th century, many Germans had visited Japan over the centuries working for the Dutch (see on this website, ‘The Intermediate Period’ and ‘Japonisme of the 16th – 18th Centuries’)---not only Siebold, as Josef Kreiner, Professor at Bonn University and President of the European Association for Japanese Studies (EAJS), has emphasized. The same could be postulated about the simple folds for birds, hats, or boats that existed in Spain or Portugal. These too, like the folding fan, must be considered in light of the centuries old trade and residency of Iberians in Japan. An indication that these folds, though differing from those of Japan, might originally have been inspired by observing Japanese folding practices, is their limited and static existence in Europe, lacking the trajectory of development that Japanese folding shows, reflected in so many aspects of Japanese religion, daily life, and art, increasing in complexity and popularity with the passage of time.

A comparison of Japanese and European paper follows, the first three images adapted from Koshiro Hatori, 'History of Origami in the East and the West before Interfusion', Origami 5, 2011. The last image is from the Senbazuru Orikata of the 100 crane fold (actually 97). The much greater diversity and sophistication of Japanese folding is self-evident.

The history of the origins of European folding is rather narrowly focused, primarily upon German baptismal certificates, the patenbriefs, or taufbriefs of the 18th century, with little artistic evolution until the 20th century. The primary shape was the ‘double blintz’, or a folding of all four corners of a square to the center and repeating the same folds on the smaller square. Comparing Japanese wrappers with the European baptismal certificates, for instance, the crease lines of folding styles in Japan run in a wider range of angles; while those of baptismal certificates are limited to square grids and diagonals. It may be said that in general, the applications, shapes, and complexity of Japanese paper folding was noticeably richer than elsewhere in the world, and evidence remains in a variety of visual arts and literature attesting to it.

The Global Spread and Recognition of Origami as we Know it Today

It was after World War II that Japan origami was recognized as an art form and came to practiced globally, thanks in large part to Yoshizawa Akira (吉澤章1911-2005), considered by many as the father of modern origami. A highly creative, prolific, and masterful craftsman, his astonishingly artistic models of flora, fauna, and other objects captured the imagination of many thousands domestically and internationally. Passionate about origami, he tirelessly conducted seminars and exhibitions around the world. Much of the credit for origami’s present day global popularity must go to Yoshizawa, who is still held in high esteem by the international community of origami artists.

Yoshizawa designed countless patterns and developed the current standard for diagramming origami instructions. He avoided the accepted cutting techniques used in traditional origami and developed the ‘wet folding technique’ which rendered pieces softer and more naturalistic. Yoshizawa’s Origami Tokuhon (折り紙読本 1957) which brought him great acclaim, was the first in a series of books on origami. In 1983 he received one of Japan’s highest honors, ‘The Order of the Rising Sun’.

We should also mention Uchiyama Kosho (内山興正1912-1998), a Soto Zen priest and origami master, who also contributed to popularizing origami. Following the footsteps of his father Michio, also a priest, who had also written books on origami, Kosho's instructional books for children, published in the late 1950's and 60's were widely read, followed in later years by several more books on origami as well as on Zen Buddhism. Like Yoshizawa, several of his books were translated and shared with international audiences. Most origami books published by later Western authors took much from these earlier books which had been translated into English and other languages. An interesting topic for investigation is whether Uchiyama's books on zazen (meditation), the Zen of cooking, and his writings on origami were an inspirational source for books like Martin Prisig's bestseller, Zen and the Art of Motocycle Maintenance, and other works like it, published in the 1970's.

Math, Engineering, Architecture, and the Diversification of Origami Applications

What we will call here ‘Origami Japonisme’ is not simply about the influence of Japan’s traditional paper folding art on modern art and architecture; we must also point out the influence of modern Japanese 'origami-no-kagaku' (折り紙の科学 origami science) and 'origami-kogaku' (折り紙工学 origami engineering), as well as Japanese origami-related software, and their impact upon global art, architecture, math, science, technology, and product design, as a critical aspect of this global japonisme phenomenon.

One of the leading online architectural platforms, RTF (Rethinking the Future), sees origami as spawning “dynamic folding artworks” which “paved a way for a new aesthetic in architecture and allied fields.” And that “Integration of Origami in the design process has successfully fulfilled the quest for achieving novel forms.” It acknowledges that “This art originated from Japan and then became a common practice in the rest of the world. Now, there isn’t a single school that doesn’t teach students how to make 3D sculptures using flat sheets of paper.” (For an example, see University of Maryland, ‘Origami Structures’ Dan Novak May 13, 2019, at arch.umd.edu).

In all of this, the contribution of Chatani Masahiro has been critical: “In the early 1980s, the Tokyo Institute of Technology appointed architect Masahiro Chatani as a professor. At first, he began experiments with origami to create unique and interesting pop-up cards. He then used origami techniques to create architectural design and create patterns, playing with light and shadow. These creations emphasized the shadow effects of the cuts and folds. Origami architecture is a convenient way for architects to use paper and visualize their designs in 2D and 3D forms. This gives their design more flexibility and a better idea of their concept rather than sketches.” (www.re-thinkingthefuture.com)

Origami is attracting worldwide interest across fields. One of the more lucid commentators on origami architecture, Jorge C. Lucero, Professor of Computer Science at the University of Brasilia, Brazil, writes in ‘Origami Building Designs: The Inspiring Power of Paper Folding in Architecture’:

“Japanese architect Masahiro Chatani was one of the first pioneers to adapt origami techniques into built forms. Chatani’s early experiments showed the enormous potential of paper folds and creases for architectural expression. He unlocked ways to translate the intricacy, beauty and geometry of origami into new construction methods and materials. Since Chatani’s groundbreaking adaptations, origami architecture has steadily gained global interest and momentum. Today, origami building designs are pushing the boundaries of architectural creativity and performance across the world.” (at onefoldatatime.com)

Professor Lucero succinctly summarizes the technical aspects of origami architecture:

“Folds and creases form the basis of origami architecture. Architects use fold patterns to create angular, multi-faceted building geometries. Folds interlock interior spaces and add textural interest to facades. Pleating allows surfaces to expand and contract like an accordion. Architects employ pleating to make kinetic building skins that adapt to changing sunlight and other environmental conditions. The Miura-ori or pleated fold technique has been used in conceptual retractable roof designs [Miura Koryo (三浦公亮), professor emeritus of the University of Tokyo; his geometrical crease pattern by which a single sheet of paper can open and close in one movement]. Tessellations involve repeating origami shape units in intricate modular patterns without gaps. This makes them ideal for building facades and skins, mimicking patterns found in nature. Kirigami builds on origami by making strategic cuts in folded materials to allow greater flexibility and motion. The voids create negative space that can become windows or doorways.”

Due to the geometric nature of origami, it is also a well-established field of mathematics in Japan. Just a few examples are Kawasaki's Theorem and Maekawa's Theorem, which follow: The Kawasaki Theorem---The patterns of crease lines meeting at one vertex are flat-foldable if and only if the alternating sum of the angles is 0. The Maekawa theorem---At every vertex on a flat-foldable Origami crease pattern, the numbers of mountain and valley fold always differ by 2. Interestingly, the discoverers of these theorems, Kawasaki Toshikazu (川崎敏和) and Maekawa Jun (前川淳), are both origami artists and mathematicians. (See Kyushu University Library, ‘History of Origami: Origami as Science’ at guides.lib.kyushu-u.ac.jp) In Japan, often science and art intersect, where art is the stimulus for science, and vice versa. Thus Japan has not only provided the original art of origami, but also the science of origami which follows from it.

The above are but a few examples of a mathematical appreciation of origami existing early on in Japan. And while the Japan Origami Academic Society’s Origami no Kagaku (Journal of Origami Science) has been published since 2011, the Society had been publishing math articles in its pre-existing journals, not to mention the fact that numerous Japanese universities had been publishing origami related findings in math for years. Likewise in engineering, where origami based technology is called 'origami-kogaku', and one of its foremost researchers, Hagihara Ichiro (萩原一郎) at Meiji University, set up a society for origami engineering research in the post-WWII period (see related Meiji University sites at https://www.meiji.ac.jp). Japanese software designers were the earliest to produce origami specific tools applicable to product and architectural design, such as Mitani Jun (三谷純)'s open source ORIPA Origami Pattern Editor (2005); ORI-REVO: A Design Tool for 3D Origami of Revolution (2011); ORI-REF: A Design Tool for Curved Origami based on Reflection (2011); among others (https://mitani.cs.tsukuba.ac.jp/ja/software.html).

As RTF notes, “The advent of computational data and digital fabrication have greatly favored the adoption of Origami in architectural practices. Initially pioneering in its place of origin, the free form folding process of design gradually spread from Japan to Europe, the USA, and other parts of the world.” Origami is also used as a means of storing and deploying structures in the field of engineering; Computational Origami uses IT to design origami in computer science; from NASA and Space X to biotechnology, origami science and its applications are now experiencing explosive growth. Others are investigating the acoustic properties and solutions that origami has to offer (see ASI Architectural at asiarchitectural.com). As for the innumerable consumer products that have sprung from origami inspiration, ranging from fashion to vehicle design, see the Dezeen website (www.dezeen.com/tag/origami). While lesser minds, East and West, dare not fathom it, the fact is, for great spirits, all intellectual and creative roads lead to Japan.

This author guesses that Elon Musk's 'Cybertruck' is also based on origamic design principles. Looking into it, he found the Yanko Design article, 'This Tesla Origami Concept is the Sci-Fi Blend of Cybertruck and Nasa Rover!' (Gaurav Sood, 02/26/2021, at www.yankodesign.com). According to the designer, the design for a prototype Tesla car is based on origami; while in the case of the Cybertruck, we are pointed this way and that-a-way. But as NPR records (in the next article this author located, sure enough), in an interview with the Italian car designer of the DeLorean, Giorgetto Giugiaro, "Giugiaro called this design approach 'origami.' " And not only the DeLorean or the Tesla Cybertruck:

"In 1972, his [Guigiaro] concept car for Maserati, the Boomerang, launched a whole new look for cars based on wedges and sharp, straight lines inspired by Japanese origami. The most famous commercial application of this 'folded paper' style would be the Volkswagen Golf Mk1, but the effect is visible in all the angular car designs that followed, Esquire reported in an exhaustive profile of Giugiaro in 2019." (NPR, 'The legendary designer of the DeLorean has something to say about Tesla's Cybertruck', Fernando Alfonso III, Nov. 14, 2023, at npr.org).

Indeed, origami is revolutionizing design psychology and processes in a most fundamental sense. As Zoe Cooper, writer at the popular architectural publication Architizer puts it: “Dating back to the early 17th century, the Japanese practice of origami has influenced the way design projects are conceived and constructed.” Even today, despite having CAD type computer graphics designing software, in graduate design courses and at professional design teams, “As per tradition, each person is given a square sheet of paper and asked to transform the material into a sculpture without using scissors, glue, or pens — only strategically placed folds. These limitations make a seemingly simple design challenge much more difficult, forcing us to think outside the box and pare down our ideas to concepts that can be communicated with only flat planes and sharp angles. Origami’s compelling minimalist aesthetic continues to influence contemporary architects, whose work pictured below takes visual cues from Japanese tradition.” (Numerous examples of origami architecture from around the world are then provided in the article.)

Origami works at all phases of design from beginning to end: “For architects, origami can be a helpful tool in the early ideas phase of a new project, or alternatively, in creating 3D models of completed buildings.” More recently, origami-based designing and technology is being applied to the finishing touches of structures as well. Cooper sees origami as expanding the frontiers of architectural design: “Using traditional origami techniques, designers can experiment with shifting planes and hard edges to push formal boundaries.” (‘Origami Design: 10 Projects Inspired by the Japanese Art of Paper Folding’ at https://architizer.com. Visited 2024.7.8)

And as Lucero relates, origami provides architects with “hands-on models to visualize and iterate designs before construction” giving designers “an expansive new toolkit”. He summarizes the ‘Key Advantages of Origami Building Design’ as compared to conventional building with the following bullet points: 1) Sculptural, organic forms and textures 2) Lightweight, materially efficient structures 3) Kinetic, adaptable facades that modulate sunlight and views 4) Rapid on-site deployment and deconstruction 5) Sustainability through passive solar control and ventilation, and 6) Spaces reconfigurable for multi-functional use.

Examples of Origami Architecture

It would be impossible to recount all the origami inspired designs proliferating across the globe today. Some are called outright ‘origami houses’ or buildings, such as the following:

Belzberg Architects, 'Origami House' in West Hollywood, California, USA. Waechter Architecture, 'Origami' (multi-family housing) in Portland, Oregon, USA. IwamotoScott Architecture, 'Cellular Origami' in San Francisco, USA. NMD|NOMADAS, 'De Candido Express: an origami as a free-standing building', in Maracaibo, Venezuela. Benardes Arquitetura, 'Origami House' in Porto Feliz, Brazil. Manuelle Gautrand, 'Origami Office Building', in Paris, France. AR+TE, 'Origami Peace Dove', in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France. Fran Silvestre, 'Origami House', in Valencia, Spain. OAB Carlos Ferrater, 'AA House', a.k.a., 'Origami House', in Barcelona, Spain. MSSM Associates, 'Origami House' in Nicosia, Cyprus. Alexis Dornier, 'Origami House' in Bali, Indonesia.

Others are widely recognized as such or are known to have used origami principles or technology to create their designs:

Lucero includes early examples of origami architecture: Santiago Calatrava, Gare do Oriente (railway station), in Lisbon, Portugal (1998); Quadracci Pavilion of the Milwaukee Art Museum, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA (2001). Office Kovacs, Helios House (gas station), in Los Angeles, USA (2007). Mario Cucinella Architects, Centre for Sustainable Energy Technologies, in Ningbo, China (2008). Niall McLaughlin Architects, Bishop Edward King Chapel, in Oxfordshire, England (2013).

Examples raised by RTF, built within the last decade or so include: Coll-Barreu Arquitectos, Bilbao Health Department, in Bilbao, Spain. Studio Gang, Bengt Sjostrom Starlight Theater, in Rockford, USA. Daanilo Mondada LOCALARCHITECTURE, Chapel for the Deaconess of St. Loup, in Pompaples, Switzerland. HHD_FUN, Embedded Project, in Shanghai, China. Preston Scott Cohen, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, in Tel Aviv, Israel. Rojkind Arquitectos, Nestle Chocolate Museum, in Toluca De Lerdo, Mexico. Moneo Brock Studio, Park Pavilion, in Cuenca, Spain.

Examples raised by Architizer include: NORD Architects, Healthcare Center for Cancer Patients, in Copenhagen, Denmark. Harrison and White, Foyn-Johanson House, in Northcote, Australia. Dominique Coulon & Associés, Médiathèque d’Anzin, in Anzin, France. Cobaleda & Garcia Arquitectos, Zigzag House, in Pozuelo de Alarcón, Spain.

Examples raised by Origami.org include: Jürgen Mayer, Metropol Parasol (“Mushrooms of Seville"), in Seville, Spain. Daniel Libeskind, Felix Nussbaum Haus, in Osnabrück, Germany. Jean Nouvel, Louvre Abu Dhabi, in Abu Dhabi, UAE. Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), Serpentine Pavilion 2016, in London, UK. Also mentioned is the iconic 2008 Beijing Olympics Water Cube, or the National Aquatics Center; and the Paper Dome of Taomi Village, Taiwan.

Examples raised by the company Rouveure-Marquez include: Aranguren & Gallegos Architects, Museo ABC, in Madrid, Spain. Coop Himmelb(l)au, Musée des Confluences, in Lyon, France, among others already mentioned above.

Other designs of interest that have been discussed as examples of origami architecture are: Henriquez Partners, Cadero, in Vancouver, Canada. CrystalZoo, Coworking LAB Nuncia, in Alicante, Spain. McBride Charles Ryan, Klein Bottle, in Rye, Australia.

Again, the above is a mere sampling of a truly global phenomenon. Almost every kind of architecture, from educational facilities as ATI Consultants, Architects & Engineers’ International School of Choueifat, in Umm Al Quwain, UAE, on to Justo Garciá Rubio’s Casar de Caceres Bus Station, in Egido Bajo, Spain, or Dashi Namdakov and Parsec Architects' Russian Pavilion Expo '25 in Osaka (underway project) utilizes the principles of origamic architecture, whether fold-only origami or kirigami cut modeling.

Other designs, though perhaps not openly proclaimed so, in hindsight must be considered in the light of origamic architecture include Cox Architecture's Albany Entertainment Centre in Albany (Australia), and various other projects; Mehrdad Yazdani's Shooting Range and Academy in Dubai and his Cinemania Theater in Los Angeles; Jan Søndergaard's Danish Pavilion Expo '92 in Serville, Spain (now Japan); Zaha Hadid’s Maggie’s Centre, in Kirkcaldy, Scotland; Gigon/Guyer Architekten’s Henze and Ketterer Gallery, in Wichtrach, Switzerland; and Paleko Arch Studija’s Litexpo Exhibition Pavilion, in Vilnius, Lithuania; Dirk Denison's Illinois Residence in northern Illinois, USA; to name a few. Frank Gehry's works, including the Guggenheim Museum, in Bilbao, Spain; Walt Disney Concert Hall, in Los Angeles, USA; Biomuseo, in Panama; Fondation Louis Vuitton, in Paris, France; Marqués de Riscal Hotel, in Elciego, Spain; for example, clearly reveal the origamic, paper-based modeling they are derived from, of which the kirigami, or the cut paper approach, is most conspicuous. His Bard College, Fischer Center for the Performing Arts, at Red Hook, NY, looks literally like commonplace silver sheets of square origami paper, bent and pasted together.

Conclusion: Origamic Architecture, Origamic Perception, and the Origamic Imagination

Text to be added on the culture and psychology of origami; for there can be no true understanding of any art form cut off from its cultural context.

'Shinsenjinbutsu Orikata Tehon Chushingura' the Chushingura story told with origami figures, note too this is an early cartoon

* * * * * * *

* Regarding the 'sankaku-ori' (triangular fold) of toilet paper at Japanese hotels, which has now spread worldwide: A good number of years ago, this author had researched the origins of the toilet paper triangular fold, and back then there was detailed material on the web regarding its practice in Japan. It is one of those thousands of commonplace things overlooked in most cultural and social histories of the everyday, but make up the appearance of this world in all its details---a dimension of human existence in which Japan has played a particularly large role in making. And it is in these mundane details where at times the key to our understanding more complex artistic phenomenon may rest; an idea which perhaps Marcel Duchamp would agree to. The author's electronic files regarding this topic are missing; nevertheless, the general outlines of that history can be summarized as follows: It is in the late 1960's that the practice first arose in Japan. Some of the earliest cases may be that of Tamura Junko (田村 順子)'s folding the ends of the toilet paper in a triangular form, in what she called the 'upside down Fuji' (逆さ富士), at her nightclub, Club Junko, located at Ginza 6 chome, in Tokyo, from 1966, though this requires verification and further investigation. In 1968, Hotel Hokke Club, a national chain of hotels, started to fold the ends of toilet paper into the triangular shape with the installation of the new style 'unit baths' (Japanese style pre-fabricated bathrooms) in their hotels, as confirmed with the hotel, broadcasted on Feb. 1, 2015, in the Nihon Terebi channel show, 'Bakusho mondai no sorette itsukara? Hisutori'. However, this is only one example of what was a growing trend in Japan, of which this author had documentation for other hotels as well. In any case, by the end of the 1960's, the practice was being institutionalized in Japan as a confirmation, for both fellow staff and hotel guests, that the cleaning of the bathroom had been completed by the hotel cleaning staff. From there, in the following decades, there are those in Japan who took toilet paper folding a step further into more complex origami type creations. What is interesting to observe is how Japanese searches on this topic in the present (July, 2024) lead first to a set of sites of different character as compared to a decade or so earlier. Nowadays, the initial several pages of results first list the 'Fire Hold' origins of toilet paper folding, said to be practiced by firemen at fire stations in America (something not mentioned when the author first started researching the topic). This preposterous theory, which says American firemen (and possibly fire station janitors) have been delicately folding the ends of their toilet paper into triangles for the past 6 decades, so that they could more efficiently wipe themselves before rushing off to a fire---is passed off as the origins of the 'sankaku-ori'---a case study of growing historical obfuscation and gullibility in 21st century Japan, and mirroring an emphatic denial of indigenous originality that has taken hold of mainstream Japanese scholarly opinion in the past two decades.

________________________

Uploaded / published 2024.6.30; under construction, text to be added and revised, photos to be further annotated

Towards a Better Understanding of Architectural Evolution

Inevitable Transformations

of

Traditional Japanese Design into Modernist Architecture

When Transplanted Abroad

Yasutaka Aoyama

The use of the word 'inevitable' is intended to be provocative, to emphasize the natural process by which Japanese architectural features are adapted in Western nations and the predictable results they produce, when combined with markedly different practices of design, construction, carpentry techniques, and contrasting lifestyles from that of Japan.

The following examples are primarily from Jay van Arsdale's Shoji: How to Design, Build, and Install Japanese Screens (1988), chosen because it shows the practical considerations and techniques by which Japanese shoji are installed in homes in America and provides many illustrations. Though published after the architectural examples that follow, the issues confronted and the solutions provided in the book are based on time-proven techniques of shoji construction and adaptation already in use decades earlier in the United States.

Any number of Japanese architectural features could have served as a focal point to illustrate the process of transformation from traditional Japanese design to Modern architecture, such as vertical grills known as 'koshi'; 'engawa' balconies; built in 'tansu' cabinetry or closets 'nando' / 'shiire'; display alcoves called 'tokonoma'; wood joinery; various ceiling treatments including exposed beam work; etc., but the shoji are a particularly conspicuous, 'iconic' feature of Japanese architecture.

Many building examples, where the architect has openly expressed the design as one emulative of traditional Japanese architecture, have been provided, so as to dispel any doubts of the relation to Japan of their designs and the popularity of shoji in America. And unless a good number of such examples are shown, the skeptical often see such cases as exceptional rather than reflective of a much larger trend. Finally, and of no less importance, to give credit to such designers, for despite the good work they might do, are often not as celebrated as those who eliminate the identifying cultural markers of what is still fundamentally Japanese in design.

Captions have been included from Arsdale's book, as well as those from other design examples taken from websites, so that the reader can see for himself how the designs discussed here are not simply posited by this author as being Japan-inspired, but stated as such by the architect himself and generally recognized as so by those familiar with the properties in question.

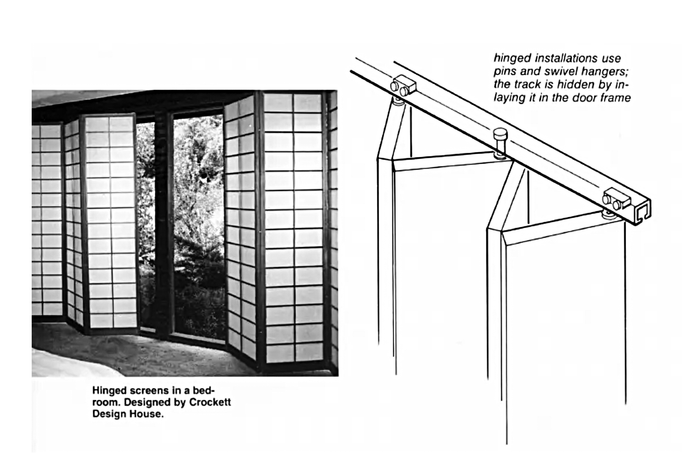

A good example of that process of natural transformation is the adaptation of shoji screens to a Western living environment and traditions of construction. Accompanying the conspicuous structures themselves that provide the desired look are the less noticeable but necessary structures and skills so that they fit and function smoothly, such as the built-in ceiling and floor tracks, which require expertise in traditional ‘tategu’ carpentry---that is carpentry specifically concerned with the building a fitting of doors and moveable parts of a house. This also requires a standardization of sizes according to Japanese tradition of the rooms, passageway heights, and without tatami, would mean protruding track rails or a recessed channel cutting across a wood or stone floor. In a Western house these are not practical nor do they result in an aesthetically pleasing design. The quickest solution is the construction of metal rails and hangers attached to the top surface of the screens, and then hid with a valance or otherwise recessed into the ceiling. Doing so means that shoji screens themselves are of a too fragile construction not to start warping or become damaged, thus the unavoidable thickening of the elements if in wood or the use of metal frames---resulting precisely in the modernist-looking sliding screen. Another predictable variation is the hinged folding screen with swivel hangers, as shown to the right.

It is not difficult to see how once an architect wishes to incorporate shoji screens into his design, whose soft filtering of light is one of their most appealing qualities, that using such screens to cover lighting, attaching them not only on window surfaces or as wall partitions, but as coverings for wider, longer overhead lighting is not difficult to imagine. In fact, shoji boxes as ceiling lamps were a natural evolution in Meiji Japan interiors. Due to the low ceilings of common residences, and the emphasis on extending horizontal lines from an aesthetic perspective, these types of lamps were often of restrained height and size, contrasting in form and aesthetic conception to European chandeliers. This effect was also reproduced in Prairie and Craftsman style homes, as well as in Mid-Century Modern designs.

The so called 'sandwich shoj' was also a natural result of transplanting shoji to American and European homes with large, fixed windows. Unlike Japanese houses, which had often an additional exterior layering of amido panels (rain doors) as well as perimeter walls just high enough to obstruct views of the house and garden from the outside thus making the viewing of shoji from the outside not an issue, in the West house facades being often intentionally visible---considered normal for a proud home owner---and where fences were either waist high or iron grills to keep the exterior visible (so as not to provide a cover for potential burglars as well as due to differing conceptions of privacy); or otherwise extremely high walls difficult to clamber over. Though over the years, Japanese conceptions of fencing have spread in the West, and what was done for only large estates, nowadays there are taller fences on even small plots facing the street. In any case, as in the caption above (right) the desire for a Japanese effect naturally leads to the use of shoji visible from the exterior. Again, the result is very much like late 19th to early 20th century Prairie/Craftsman houses, when combined with the sloping Japanese roof and rafter ends showing; and when done in a concrete structure with a flat-topped roof it results in a modernist look. These results in a sense may be said to be unavoidable and a natural evolution that was occurring not only in the West due to the influence of japonisme, but earlier in Japan from the Meiji period onward as Japan incorporated Western elements of construction and architectural styles.

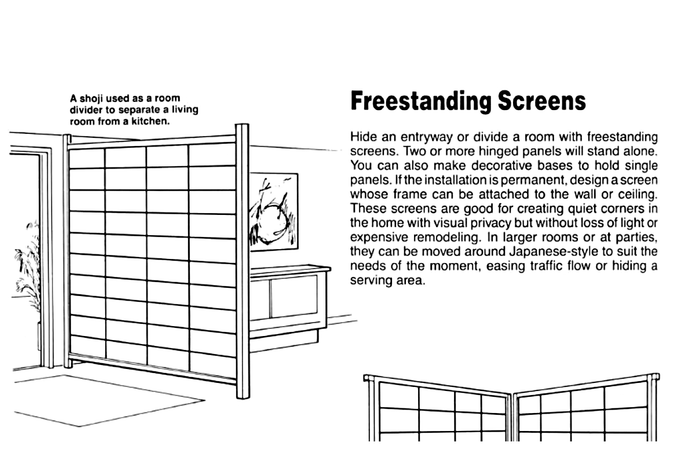

The above is an example of how byobu screens and sode-kabe type features ('kimono sleeve'-like partitions which extend from solid walls) are adapted in a building of modern construction. The typical variations that occur in Western interiors are the reduction or simplification of the grid, substitution of construction material, and the addition of colors, sometimes paints, to match the interior and tastes of the patron, which most often differ from the traditional natural tones that are typical in Japan (while bright colors can be employed in Japanese interiors, they are of that certain pastel-like color that is found in traditional chromatic sources used for paper, dyed fabric, or mixed within the paste for walls). The visual transformation by such simple differences however, situated within a more Western style interior, makes the freestanding screen (including the ubiquitous interconnected, open office screen) unrecognizable as Japanese, but in fact is the same in concept and origin.

Examples of Natural and Predictable Adaptations of Shoji with Modern Results

Must be emphasized that the following architects represent a small sampling of an unrecognized undercurrent of traditional Japanese and 'Japandi' architecture around the world, especially in the United States and East / Southeast Asia, of which only a few examples can be presented here.

Above left is a Charles Warren Callister (1917-2008) designed house with shoji screens. "I say the Japanese current that goes past us out here is really an influence" Callister is reported to have said, hinting at how California's location facing the Pacific, and towards the East, was important to his work. ( 'Appreciation: Architect Warren Callister', Dave Weinstein, Special to the Chronicle, May 31, 2008, at www.sfgate.com) As architectural reporter Dave Weinstein observes, "His expressive use of wood joinery recalls Japan and the work of Arts and Crafts architects Greene and Greene." ('Signature Style / Warren Callister', Special to the Chronicle, March 6, 2004) We should not forget that the wood joinery of Greene and Greene was very much influenced by that of Japanese Buddhist temples; but looking at Callister's joinery here we find it is more of the vernacular Japanese type, perhaps closer to the look of some Bernard Maybeck designs. The attempt to create a Japanese style interior by a combination of exposed Japanese type joinery, shoji, and chochin style lighting fixtures, 'compromised' with glass windows and matching wood furnishings, is something that invariably produces a Craftsman architectural look.

To the right, Vernon Demars' Japanese style interior with shoji. The low ceilings and simple rectangular cabinets, evoking light colored unvarnished kiri-dansu, fit snugly between a turn in the wall and the extending built-in wood bench which abuts it, form a window alcove---which is a means of approximating a tokonoma alcove. The clean, integrated look which one arrives at, with a modernist feel to it, is reminiscent of Irving Gill.

The attempt to create a Japanese effect in Western interiors while maintaining swinging doors and painted surfaces rather than sliding, unpainted wooden panels naturally leads to a door with a fine lattice commonly in white or beige, matching the walls, as is the case in Japanese houses where the walls are off-white plaster or exposed wood---to match either with the shoji frames or paper, as seen in the Parsons Design Group interior to the left.

Likewise when shoji are lined up, forming a background for Western furnishings with low backrests---it immediately transforms the room into one with a modernist atmosphere, as in the example from Gensler Associates to the right.

Below to the right is a 'washitsu' or Japanese room created within a larger living area, often in a modern style house or apartment, a common practice in Japan and occasionally attempted in the United States and Europe. This immediately creates a De Stijl type of spatial relationships, by its interlocking. intersecting, and perforated volumes and planes.

Above left is a hallway of one of a group of 3 residences built specifically as 'Japanese houses' at Oakland Hills, Oakland, CA in the 1980's by architect Robert Brockob. Immediately below it by the same architect is a living room from one of those houses, each with slight variations in their Japanesque aspect. Since the elaborate and difficult craftsmanship, and raising of the roof and erection of the ceiling timbers is done by complex coordination and procedures based on experience in traditionally built Japanese houses, Japanese style homes abroad necessarily entail a simplification of the the interlocking ceiling timbers and ceiling surfaces (which in Japan may be composed of complex woven natural woods sometimes using bark or bamboo). The beams for practical purposes and cost considerations are often fewer and thinner, and the ceiling surfaces are smooth and boarded with parallel planks made of pine or other domestically obtained wood as shown in the photo, creating a 'Japandi' effect which in result looks modern, or ‘Scandinavian’.

The clear outlines of a Japanese house due to the thick pillars at every corner and the black lacquer edges of fusuma sliding doors is also not practical which requires built-in floor tracks. Thus hanging, sliding screens with valances, thick, dark window frames take their place, again resulting in a modern look. In the photo to the right, David Putnam who had studied Japanese carpentry for many years, known for his Japanese school of carpentry, is able to create a more authentic ceiling and walls, and thus looks more traditionally Japanese. However the floor boards are done in typical American deck style, and thus a somewhat mixed look.

Some more examples below of 'self-proclaimed' Japanese style houses built in the United States. Cultural practices such as wearing one's shoes in the home and sitting on chairs means that chairs or sofas are necessary and tatami are not installed. The backrests and armrests of furniture are kept to a minimum in line with the effort to create a Japanese-looking room; and counters are often long and extended boards, as building a real tokonoma alcove with staggered levels and cabinet constructions is something of considerable complexity. Such built-ins are also kept at a low level, as if they were being used as in a Japanese house, accessible and to be viewed from a floor-seated height. There is nothing necessarily modern about having low backrests and countertops in terms of functionality, efficiency, and structural needs (there are tall folks with long legs who could use a high seat and good backrest). One need only take one step back to see that the reason modern furniture has a low center of gravity is because of the Japanese custom of sitting on tatami mats and building houses and furnishings accordingly, and not due to any modernist imperative.

As can be seen in the photo to the right, the simplification of the tokonoma results in low built-in wood counters, sometimes vertically long pictures, and like ikebana, that is Japanese flower arrangement, a relatively sparsely bunched floral /vegetal arrangement, with asymmetrically extending branches or twigs---so common in modernist interiors. Again, there is nothing inherently modern in such features, they are the natural result of emulating Japanese interiors.

Just a few more examples of Japanese inspired bedrooms. Once again, the installation of shoji often suggests a matching off-white for bedroom walls or otherwise natural woods; the furnishings are usually without legs and boxy, following Japanese tansu forms; the bed level lower than usual, often close to the floor reflecting the Japanese practice of sleeping on futon on the floor. The result of attempting to create a Japanese style bedroom with Western compromises produces once again the look of modern bedrooms, such as those of the key British modernist Coates Wells, for instance.

To the left is a bedroom in the home of architect David Graeber, one of Austin's leading architects in the 1970's to his retirement in 1995, designed by himself, and the entire house was meant to be Japanese in spirit. To the right is a room of a house designed by architect and builder Al Klyce (1931-), someone with deep ties to Japan. As related in Calisphere of the University of California (archives devoted to the history and culture of California), Klyce was "introduced to Zen Buddhism by Alan Watts in 1951. Al subsequently moved to Japan to study carpentry, and stayed there for two years. In Osaka, Al met his wife Shoko, and after moving back to Mill Valley they raised three kids together." ('Oral History of Al Klyce' at https://calisphere.org)

For perspective as to what kind of house the above type of bedrooms might be found in, a photo of Graeber's house is shown below, from the Moreland Properties website. Under the title of 'Custom Japanese-Inspired Mid Century Modern Abode' (07/01/2019), the description follows: "Tucked into the hillside along Balcones Drive, this one-of-a-kind 1959 home was designed and lived in by world-renowned architect David Graeber, the architectural visionary behind Houston’s Johnson Space Center and mastermind behind the revitalization of 19th century buildings on famed 6th Street. From every angle of this home, whether inside or out, Graeber’s vision of a mid-century modern home with subtle Asian flair is perfectly executed."

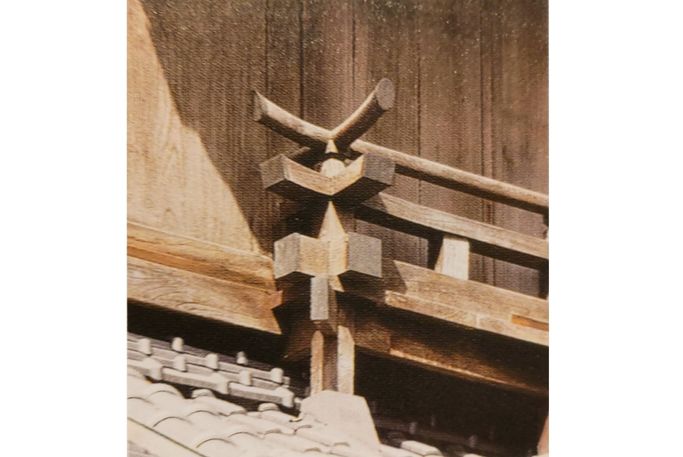

What is difficult to comprehend though, is just how much the house owes to Japanese inspiration, which at first glance might look like simply another 'mid-century modern' with Craftsman tendencies. While many of the Japan-inspired features such as wood lattices, raised construction, Japanese style asymmetry, bathrooms using natural stones, and the like, have been modified or substituted with more easily or conveniently built structures, some aspects remain relatively faithful in form to traditional Japanese design, such as the 'hane-kouran' rails intersecting and shooting out and upward like horns, of which a Japanese example, the Kodera Soy Sauce Shop (now in the Tokyo Tatemono-en outdoor architectural museum), is provided to the right. Originally the hane-kouran were a feature of shrines and temples but came to be used on residential and commercial buildings, especially on second floor balconies for their visibly decorative effect. These sorts of analogies, however, go unnoticed for vast majority of both Western and Eastern visitors to such a house and others like it, whose peculiar design features are simply attributed to the originality of the architect.

Fireplaces are a inseparable feature of most houses in the West, which few wish to forsake. Naturally this means even when attempting to create a consciously Japanese style interior, a fireplace must be accommodated, without conflicting with the lines, low center of gravity, and atmosphere desired. This leads to the placement of an unadorned, brick or stone fireplace, often with asymmetric qualities, without conspicuous mantlepieces and mirrors or paintings above it. Usually a flat surface which merges with the walls is the solution, as in the example shown below, left. Again, this is reflected in fireplace design in modernist architecture.

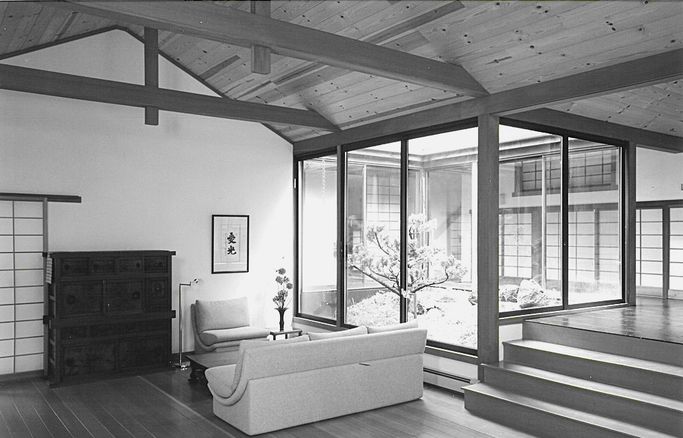

Stephen Macdonald is considered one of Utah's earliest and foremost modernist architects. He directly incorporated many Japanese architectural, landscape, furniture, and ceramic objects into his designs. One can see how Japanese aesthetic sensibilities, not only the shoji panels, but the nakaniwa (indoor) garden and the ibitsu ('bumpy') shaped sake beaker/carafe on the table form a nice textural and configurative balance, congruent with modernist artistic sensibility, precisely because they all sprung from the same cultural source, and evolved together from the start. Even the chairs, which at first glance might be considered a purely Western element, are similar in concept to Japanese folding chairs ('koui' 交椅) for field use in the Muromachi period (similar to, and perhaps the origin of, the 'film director's chair'); and chairs not so unlike the ones shown above can be seen in pre-Meiji era photographs of the homes of Western residents, American and British, in Japan (see article on Le Corbusier, on this website), in the decades after Commodore Perry's arrival, before such types of chairs came to be used in the West.

The point being that the simple, unadorned, thin, cross-legged, and low-seated chair of that kind which would come to be associated with the 'modern' was chosen because it was congruent with a Japanese conception of interiors composed of shoji---likewise of simple, thin unvarnished intersecting 'koshi' natural woods---not to mention other aspects of traditional Japanese interiors. This can be also clearly seen in the example below, of Harry Jackson's furniture and interior decoration company, Pacifica's interior settings.

Text to be added.

The above from Hiroshi Emoto, 'Japonica in Architecture: Origin and Semantic Pluralism' JTLA (Journal of the Faculty of Letters, The University of Tokyo, Aesthetics), Vol.45, 2020.

The same process of attempting to harmonize design with a Japanese traditional architectural aesthetic leads to analogous results whether in Hawaii, California, New York, or Copenhagen. Below is a photograph of an exhibit on furnishings from the long running Designmuseum Danmark exhibition: 'Learning from Japan' (2015-2019), documenting the influence of, and synthesis with, Japanese design in the making of the Scandanavian style of Modernism. (Photo: Pernille Klemp, Jeppe Gudmundsen-Holmgreen, from 'Japonisme and the Origin of Modern Scandinavian Design', November 04, 2016, at ookkuu.com. See also the official Designmuseum Danmark website regarding the exhibition, at designmuseum.dk)

Text to be added, topics such as 'shibui' chromatics to be discussed.

Text to be added.

Jack Charney was a disciple of Richard Neutra, and also a Japanophile. His Beverly Hills house reproduces in almost a Disney-esque fashion recognizably Japanese design elements. To the right is the Shofuso in Pennsylvannia, by Junzo Yoshimura, originally built as part of an exhibit in New York City, and transferred to its present Pennsylvania location. The homologous nature of the airy, open spaces, with wide engawa verandas / porches, with the shoji screens slid open or removed, requires no explanation. In fact, potential sources of inspiration and faithful models of Japanese design to emulate were plentiful in the United States, scattered across the country from Hawaii to New York. The Huntington Library's Japanese House and Japanese Gardens in Los Angeles, for example, would have been an accessible and ideal model for Charney to study. The truth is, that the late 1950's and early 1960's was a period of renewed and intense interest in Japanese architecture and gardens by the artistic and wealthy of America.

The Japanese House at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens shown to the left. According to the Los Angeles Conservancy, "With a design blending Japanese and American architecture, the Japanese House is truly a product of turn-of-the-twentieth century Southern California." This comment is a prime example of confounding Japanese design with that of later American adaptations from it. The house is, in almost all respects, a near purist version of mid-Meiji period Japanese residential architecture, with extremely subtle European influence, built by the hands of Japanese carpenters for that purpose, from parts sent from Japan, by George Marsh. So great has the Japanese influence been in California, that even the Conservancy sees into it American design aspects, which in fact are also Japanese in origin.

The garden (shown right) designed by architects Sakurai Nagao and Nakamura Kazuo is contemporaneous with that of Charney's 'Minka' garden, built after the house. (Both photos from the Los Angeles Conservancy website.)

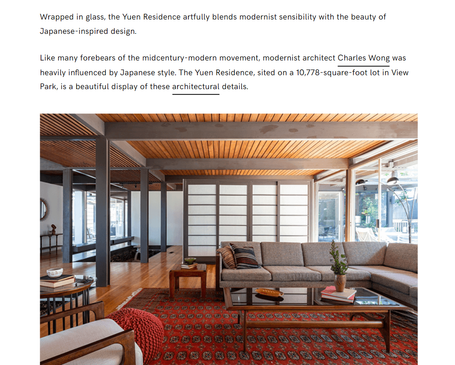

Charles Wong designed Yuen Residence

"Designed by residential architect Charles Wong in 1962, the post-and-beam Yuen Residence is an example of the burgeoning postwar influx of Japanese-inspired design in Southern California. The home's elegant, minimalist interiors blend a distinctive Japanese aesthetic with classic modernist design elements such as post-and-beam construction; a wood-paneled, tongue-and-groove ceiling; clerestory windows; and walls of glass." (Jennifer Baum Lagdameo, Dwell Magazine, April 12, 2019, at www.dwell.com)

Wong's pursuit of a traditional Japanese structural aesthetic, combined with modern construction materials and Western furnishings such as Persian carpets and the usual set of living room furnishings comprised of low backed sofas, chairs and coffee tables, produces at once a modern look. We might add here that the origins of the coffee table as a standard feature of living room assemblages is a late 19th to 20th century phenomenon, whose origin probably lies in Japanese ’zataku' that is osetsuma (living room) low tables, made for use while sitting on tatami floor zabuton cushions, as the size and height of typical coffee tables is identical to that of zataku. They may have originally been placed in the center of sofas and chairs as a conversation piece, as they were often lacquered with beautiful gold and maki-e designs. Indeed, Japanese lacquered surfaces fitted on to rectangular and round tables had long been used by European aristocrats as part of their salon furnishings. Some of the first European made coffee tables were designed by E. W. Godwin of 'Anglo-Japanese Style' fame, who consciously and assertively adapted Japanese furnishings and designs into his work. If so, this again is revealing of the natural process of Japanese designs and artifacts combined with Western elements, incorporated into a Western environment, evolve inexorably towards the 'modern'.

Text to be added.

More examples for discussion include the following: 1) the Robert De Niro owned Greenwich Hotel, NYC, coordinating architect Robert Rockwell, with designer Axel Vervoordt (aka 'Master of Wabi Sabi'), and architect Miki Tatsuro; 2) the windows of Dirk Denison's Cox Residence in Chicago, 1993; 3) the shoji-lattice window designs of Ed Smalle, Jr.; 4) interior design elements of Durbach Block Architects' Tree House in Darling Point, Sydney, 1994 (introduced in Living in Sydney, Taschen, 2001; photos by Giorgio Possenti and text by Antonella Boisi); and 5) Brian Murphy's doors to his marquee-like entry lobby in the Walker/Sheffield House, Los Angeles, among his other large grid door and window designs.

Conceptual Realizations: Shoji Transformations of Volume and Light, without Shoji Material

We must add here what the actual experience of touching and moving shoji (as well as fusuma and amido sliding screens) oneself, or having them opened by others in-front of one's eyes, may have allowed the modern architect to realize and create. This touches upon one of the core aspects of not only the Craftsman style or mid-century modern residential type of buildings we have looked at so far, but the 'International Style', applied a wide range of industrial and commercial buildings as well, that H-R Hitchcock is known for defining, despite the fact he has left out any mention of Japan (except one example of an electrical laboratory: "A straightforward building without much refinement. The rounded edges blur the effect of volume."---The International Style, 1966, p. 221. That is it. Our question is why he should need to include Japan at all, if only as a boring, unrefined example.).

Shoji create a greater sense of both enclosure and permeability simultaneously; unlike a door in a wall, the closing of the shoji on all sides creates a uniform surface resulting in a more outlined sense of geometric volume; yet with natural light permeating the space more evenly; while the sliding and removable aspect creates infinite degrees of spatial interconnectedness---these are key qualities that have been sought after in modern designs. The in situ experience of being in a house with shoji, where rooms can be immediately transformed from a box of light to a space unified with other volumes, either spaces within the building or the outside world, or anywhere in-between those two extreme states---to be adjusted as one pleases---is something unique to Japanese architecture, and needs be considered when discussing conceptions of modern architecture.

As Classical stone pillars with capitals are thought to have been originally built of wood in prehistoric times, later to be remade in stone, this process of material substitution can be seen in the reformation of Japanese architectonics from one of primarily wood and paper construction to that of steel and glass. It is in one sense, like linguistic translation, where cultural differences modulate the resulting meaning and morphology, but are relatively faithful to what was intended. The following are examples of architects attempting to create a Japanese sense of space. The Pomeroy house, shown immediately below to the left, employs both wood and paper screens as well as those of metal and glass. The image to the right is one of a more recent minimalist creation, which Takashi Yanai of EYRC, which designed the house, comments: "Japanese architecture often has moments designed for introspection. This characteristic carries over quite well into modern residential design." In both cases, the bold, contrastive framing of the windows or pillars create a visual effect similar to that of a Japanese structure with the shoji opened or removed, or with a backdrop which creates a soft light effect like that of shoji paper.

Regarding the image above right, of a meditation deck in a house by Ehrlich Yanai Rhee Chaney Architects: "A sculptural staircase invites the dwellers and their visitors to discover the open-to-sky meditation deck, which encapsulates the whole spirit of this Zen project connected to nature. Here, in California, the Japanese concept of “ma”, which refers to the notion of the interval between things, is honored through a subtle balance between the void and the built." ArchDaily, quoting Takashi Yanai (at www.archdaily.com)

Above we have another example of how the concept of shoji, or sliding panels, which can and are often opened up and thus completely reveal the interior of a house, can lead the way to more open designs. We saw this earlier in the case of Jack Charney's Beverly Hills' 'Minka'. John Harvey Carter has applied this conception to his Sacramento, California, house, which was intended to be Japanesque in design. It also reminds one of the Byodoin near Kyoto, in its spreading, open corridor-like structure and flaring, roofs of different heights, with a reflecting pond in front of it, which creates a similar effect in the evening when illuminated. In particular, the sectional proportioning under the eaves of Carter's design, where the glass windows do not go to the ceiling, but leave a large band of walling between the windows and roof in the jutting 'wing' of the building, is evocative of the Byodoin design.

Examples of Creative and Unpredictable Conceptual Extensions

The following a few relatively more imaginative uses of shoji, whose specific applications are not 'inevitable', but are nonetheless part of a natural process of experimenting and diversifying its uses once consciously brought over to foreign soil as an 'exotic' artifact. This is a common phenomenon in japonisme: the transposition of Japanese artifacts in a way different from their use in their country of origin, to serve a new purpose.

Above we see the use of shoji as a pivoting element to transform spaces and control views (left); and the bending of shoji panels to create what Arsdale calls a 'baroque visual stew'---in any case one of an infinite number of imaginative tangents that may occur when an hitherto unknown architectural element is released into a new cultural environment.

Below are some other uses of shoji---as a garage exterior (left) and a more liberal application to non-rectangular openings (right).

The article on the Andrew Herbert designed McNergney’s garage is from the Charlottesville journal, C'Ville, 'American shoji: An ancient Japanese influence bridges traditional and modern in C’ville' Apr. 12, 2023. The photo of the Nakashima's studio, 'Conoid', is from 'Upstate Diary, No. 13, Oct. 2021: The Nakashima House: Exploring space in New Hope' written by Sabine Hrechdakian, photos by Martien Mulder.

Conclusion and Commentary on the Parallel, yet Inverse Process at Work in Japan

In Japan, a parallel yet inverse process, of incorporating the Western into the Japanese (instead of the Japanese into the Western), occurred in Japanese architecture in the 19th century with traditional shoji, and shoji-like modern variations of it in the 20th century. Though more faithful to traditional Japanese aesthetic sensibilities, the process led to similar results as those in Europe and America.

In the sections on Le Corbusier and other architects on this website, we have elaborated on this natural evolution of Japanese architecture in the mid-19th century towards forms that would come to be considered 'modern', but without a conscious awareness of that evolution as something revolutionary. It was an substitution of glass for paper in screens, and the adaptation of Japanese construction to more multi-floored buildings and at other times an eclecticism using consciously European styles. The latter buildings were often hotels and houses to receive Western guests after Japan's general opening to the West, and could very well have acted as inspiration for modern architecture in America and Europe, before it assumed the mantle of a modernist rationale.

Various aspects of the Japanese model, besides shoji-type gridded screens included: 1) open floor plans or winding floor plans and oblique approaches to a building; 2) asymmetric facades with off-center entrances and irregular window placements; 3) extensive vertical grille-work in general and in furniture design; 4) but at the same time an emphasis on the horizontal line and continuous, larger window surfaces; 4) weight supported primarily by pillars; 5) intentional exposure of complex constructional elements as an aesthetic element; 6) raised floors from the ground; 7) changes of floor level within contiguous spaces; 8) built-in cabinets, shelves and counters; 9) simple and bold geometric outlining of walls; 10) larger surface areas unpainted and in a more natural state, whether wood or stone; 11) free standing, jutting out wall extensions; 12) engawa type balconies and Japanese style gardens; and other features that would be identified with modern architecture, which were being gradually adopted into European and American designs between 1855-1905. That is to say, before Loos, Le Corbusier, De Stijl, Mies, and Neutra, as seen in the Stick Style, the Shingle Style, the Queen Anne Style, the Anglo-Japanese Style, the Craftsman style, and the designs of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his generation---all related to Japanese architecture, as discussed in previous pages on this website. Thus the transmission of Japanese design elements was probably both direct and indirect---architects of the 20th century adapted Japanese design directly from books or prints, and indirectly, from those who had previously done so.

Along with such discussions, we have also pointed out the ongoing architectural evolution in Japan from the 1920's into the mid-20th century, though this time with a modernist type of ideological awareness. This process of modernization continued on course as it would have probably evolved, generally as we know it, even without the introduction of the modernist manifesto---it being so natural to combine new engineering and construction techniques and materials with pre-existing Japanese architectural forms, and to integrate them with the rest of the cultural context---as was occurring in so many areas of life in Japan. And these examples, once again, provided fresh models of how Japanese aesthetics could be applied to modern designs in Europe, America, and the rest of Asia. It cannot be over-emphasized just how much the above conception of history is at odds with the standard historical narrative of architecture as told in Japan, which, even more so than the version in Western countries, is the tale of a one-way street running West to East.

As in American examples of the use of shoji we have discussed, in modern Japan architecture, the exterior appearance of the house, both in terms of the design of the facade and the roof, is often in a contemporary style either modernist, expressionist, or otherwise, but the interiors maintain traditional conceptions of contiguous and transformable spaces in combination with the use of shoji type partitions. This has continued, done with skill, delicacy, and in complex variations across Japan, in the latter 20th century.