If the images do not appear in due time, please refresh/reload the page.

Architectural Japonisme IV

建築のジャポニスム IV

1. Eric Mendelsohn: Japonisme in Architectural Expressionism

2. Philip Johnson: From Modernist Subtraction to Post-Modern Addition

3. Murano Togo: Rethinking Post-Modernism's Origins

4. Robert Klemmedson: A Japonisme Refreshingly Honest and Open

5. Paul Thiry: 'Father of Architectural Modernism in the Pacific Northwest'

6. Harwell Hamilton Harris: 'Japanophile' and a Case Study of Reality Unconfronted

7. Vladimir Ossipoff: A Tropical Blend of Japanese Craftsmanship and Design

Image: Utagawa Hiroshige II (二代歌川広重) Shokoku Meisho Hyakkei, Kazusa Kasamori-dera Iwatsukuri-no-Kannon, 1859

(諸国名所百景 上総笠盛寺岩作り観音) The Kasamori Temple in Chiba is a marvel of architectural engineering,

possessing a tensile strength and structural configuration withstanding earthquakes for over four centuries.

Uploaded 2023/5/18

Not formatted for phone viewing, preview draft

Eric Mendelsohn (1887-1953)

Japonisme in Architectural Expressionism

'Kaoh'--Seal of the Worthies--Cornucopia of Croquis

Yasutaka Aoyama

"Where observers have hitherto seen one stylistic tendency after another, each obliterating its predecessor and pointing in a different direction, now an inner bond can be discerned. It is one that has been deliberately masked, in many cases; for artists have often been reluctant to acknowledge the existence of their 'Japanese arsenal'."

Klaus Berger, Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse,1992, p. 334 (Cambridge Studies in the History of Art)

Whether one calls it an arsenal, or otherwise a guidebook, a treasure trove or cornucopia of the imagination, the fact is: that Japanese art, artifacts, books, and cultural practices, in all their endless multiplicity of forms and ideas, produced in quantity and quality, have been a font of inspiration since the mid-19th century for many of the most acclaimed artists and thinkers in the West.

When Japanese art was a novelty, known only to few, artists could openly sing its praises and sound original; after the dawn of the 20th century, almost 5 decades had passed since the opening of Japan, and every other bourgeois family now had a Japanese fan, porcelain, or some such object. Too many artists had already paid it high tribute--thus it no longer sounded original to be inspired by Japan. But what if it still was, by all measures, the best place for good ideas, the richest of artistic treasure troves?

After ukiyo-e prints had seen their day, Western artists searched for new sources of inspiration--to keep for themselves. Places like Kyoto or Tokyo had been scourged, and yet they still had much to offer; others looked to places further away, as to the north of Japan, to its folk arts, crafts, and architecture, or to other lesser known facets of Japanese culture--or so we propose here. It is something that has already been proven to be true for many architects like Charles and Ray Eames, Charlotte Perriand, Walter Gropius, Wells Coates, Bruno Taut, and other self proclaimed Japan enthusiasts who were part of a wider circle of well-known architects.

Whether it was true for Eric (Erich) Mendelsohn, that the reader can decide for himself after reviewing the circumstantial evidence below. These varied examples should suffice, but many more could have be added.

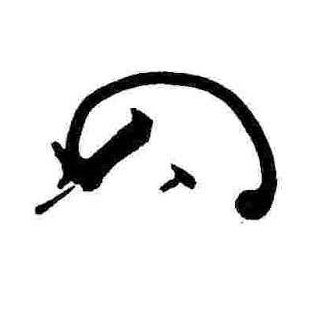

What is particularly fascinating about Eric Mendelsohn, is his particular type of japonisme: his possible use of the 'kaoh' (which we will henceforth shorten to 'kao') as a source of ideas for croquis, that is initial sketches of the basic concept of the design. The kao have been translated by certain museums as 'Seals of the Worthies'. These are not, however, stamped seals, but rather signature-like personalized artistic designs, an identifiable hand drawn 'brand' added to a signature. It was reserved for important documents and letters by emperors, aristocrats, samurai lords, high priests and the like.

While the japonisme of 'monsho' or family or business crests is well-documented (the use of monsho patterns by H. H. Richardson and the de Stijl circle has been discussed in earlier sections of this website page, and luxury brand companies as Louis Vuitton are known to have incorporated Japanese monsho into their designs), no research has been done to date on the influence of the 'kao'.

Thus Mendelsohn's case is of particular interest. It may be possible to match a good amount of his entire sketch portfolio with a limited number of kao designs. That is to say, it is not as if there are an infinite number of kao designs available; the designs of the kao can be divided into several categories, and Mendelsohn's sketches as a whole also tend to fall into those categories. He needed only to see a few books, at most a few hundred kao total, possibly less than a hundred. As the kao were employed almost exclusively by leading figures of state or religion, and because only the kao of famous or popular historical figures are usually included and repeated in kao collections, it is truly astonishing how his sketches can be aligned with those kao, not just by closely matching objective characteristics, but in a very intuitively satisfying way.

Kao often appear to be 3-dimensional grounded forms, and those are often used as elevations in Mendelsohn's sketches; while those that look 2-dimensional, and are more abstract in shape, are used as plans. The typology of his sketches, if you will, follows the broad categories of the kao in more ways than one. Furthermore, it seems there were certain kao that Mendelsohn was particularly fond of, and would repeatedly use, creating variations on a theme. The kao acts as a bridging image, making us see underlying connections between his sketches. Take the example from the series following the Einstein Tower, comparing Mendelsohn and Mori Motonari, further below. Both of Mendelsohn's images retain the same basic kao shape, but one image contains and emphasizes certain details of the kao that are left out in the other image, and vice versa. Sometimes Mendelsohn's croquis look so much like kao, that it is hard to tell them apart without the labeling, as in the example of Mendelsohn compared with Oda Nobunaga and Asakura Yoshikage, further below.

Mendelsohn's manner of drawing croquis is unique, to say the least, when compared with other famous architects, and that too adds to the plausibility of the 'kao to croquis hypothesis'. Kao simply do not to fit well with the sketches of other architects; it is this snug fit of Mendelsohn's artistic foot in the shoe of the kao, so as to speak, that makes the hypothesis so interesting. These distinctive shapes then, at the very least, are a useful tool in categorizing and analyzing the basic forms he creates. Mendelsohn's sometimes seemingly nonsensical images also become less oblique; and his entire portfolio reveals a clearer unity, when considered from the perspective of the kao.

But there are still other reasons to believe the kao were likely known to Mendelsohn. It is not just the forms themselves that are so strikingly similar, but the way his sketches were done: on small squarish pieces of paper, upon which he would draw tiny, perhaps a few centimeters in size images in the center of the paper--which is just the size and way most of the kao were printed, in the various small booklets they were contained in. And despite the small size of his croquis, Mendelsohn often drew them with what seems to be a rather thick ended pen (as if with a brush--as in Eastern calligraphy?).

After organizing and compiling the images below and the writing the above, this author came across the following extensive interview conducted by Susan King (University Art Museum, UC Berkeley) of Luise Mendelsohn, Mendelsohn's life-long spouse (who, among other things, introduced Mendelsohn to H. Freundlich, client for the Einstein Tower) :

"He read a great deal about architecture, and he also became deeply interested in Oriental philosophies. He thought that America should turn away from Europe and look more to the Orient for its inspiration. I know he liked San Francisco not only because it is a beautiful city, but because it is close to the Orient." (King, p. 26)

As van Gogh had gone south to be closer to the Orient in climate and light, so it might be said that Mendelsohn had gone West to be literally closer to a key source of his creative inspiration. However, though Luise Mendelsohn afterwards mentions China and India, as well as various aspects of European culture, but not Japan. The same can be said of Eric Mendelsohn himself, from whom we hear nothing, even of the above, in his most widely published public lectures. But this is odd, since the architects that Mendelsohn most closely associated or corresponded with included the ones most vocal in their enthusiasm regarding Japan, such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Henry Van de Velde -- the dominant avant-garde architect in Europe during Mendelsohn's early adulthood. Regarding Van de Velde, Mrs. Mendelsohn says:

"Van de Velde was extremely important to Eric, and in fact Van de Velde came to think of Eric as his disciple. Eric also felt this was true, that he was indeed a disciple of Van de Velde. He was impressed by Van de Velde’s architecture, by his sense of design, and also by his writings.” (bold added)

Luise Mendelsohn in Susan King, The Drawings of Eric Mendelsohn, p.34, 1969

If he was interested in Van de Velde's sense of design and writings, and he thought of himself as Van de Velde's disciple at the time, then how possibly could he not have understood Van de Velde's strong conviction about what he called "the sudden revelation of Japanese art" or the Japanese line being an "overwhelming revelation" and "salvation" as he had written as late as 1910?

"It took the power of the Japanese line, the force of its rhythm and its accents, to arouse and influence us. Its rhythmic strength and intensity could not but awaken even the deepest sleepers. The wonders born of a well-judged balance between the subordination that can be demanded of line and the freedom that must be granted to it came to us as an overwhelming revelation: it was like a sudden blaze of sunlight emerging from thick cloud. The Japanese line brought salvation. Its reckless courage and the boldness of its gestures, picking on the most unexpected moments to introduce an emphasis; the powerful, haunting rhythm that carries brain and soul along like the clouds of incense that rise to the Buddhas -- all this aroused our astonishment, and this strange astonishment fell on our reawakened longing for a fertility of our own like rain on the parched, yearning, concupiscent earth."

Zum neuen Stil, ('Die Linie' pp. 181-95) in Klaus Berger, Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse, 1992.

Perhaps the omission of Japan, not only by scholars but by relatives, may again be due to the phenomenon, mentioned at the beginning of this discussion, of believing they are guardians of the deceased's reputation and originality. While inspiration from ancient Greece or modern European masters is met with nodding approval, there are those who frown upon the influence of foreign cultures. As Klaus Berger, one of the foremost scholars of Odilon Redon recalls,

"When I asked Odilon Redon's son what were his father's precise Japanese sources, he bridled and declared: 'Mon père, vous savez, n'a imité personne, il était un artiste tout à fait original': 'You see, my father didn't imitate anyone; he was a totally original artist.' "

Japonisme in Western Painting, p. 334, 1992

What is clear, aside from the question of the kao, is that Mendelsohn did follow well-known Japanese architectural principles, in terms of plan, elevation, and interior decor, and that he frequently combined those elements in a single project. Several of his final plans diverged greatly from his early partis/croquis; it seems that he often used the kao as a brain-storming tool, but would come to rely on proven Japanese architectural principles in his completed projects. But that is not to say that there are a good number of completed projects that did retain the qualities of the kao expressed in the early croquis.

Let us first take look at Mendelsohn's most famous work, his Einstein Tower in Potsdam (1920), and compare it with the kao of some famous Japanese historical figures, displayed in many of the kao booklets. It is postulated that Mendelsohn would have seen these kao below, or one like them. All the kao that relate to the Einstein Tower are post 1500 and some are from the 19th century. From this, it would seem that one of the kao compendiums he viewed was one that included or focused upon kao from the Sengoku to Meiji periods.

First row: center Mendelsohn; left kao of Yoshida Shoin (1830-1859); right kao of Emperor Higashiyama (1675-1710). Second row: left kao of Reizei Tametoyo (1504-1560); right kao of Emperor Go-Komyo (1633-1654).

Below are further variations on this basic schema. First row: center Mendelsohn, left Konoye Nobutada (1565-1614); right Kato Tomosaburo (1861-1923). Second row: center Mendelsohn; left Matsudaira Tadanao (1595-1650); right Sakai Tadatoshi (1559-1627).

Below, some early croquis included. First row, center Mendelsohn; left Tokugawa Iemitsu (1604-1651); right Satake Yoshihiro (1812-1846). Second row center Mendelsohn; left Date Masamune (1567-1636); right Bunshutsu Soshu (c. 1571-1640).

Distinctive kao forms and their possible 'Mendelsohnian' transformations

First row, left Mendelsohn, Emanu-El Community Center, Dallas, Texas, 1951; right kao of Ashikaga Yoshiaki (1537-1597). Second row, left kao of Uesugi Kenshin (1530-1578); right Mendelsohn sketch for a theater, 1917. Third row, left Totoyotomi Hidenaga (1540-1591); right Mendelsohn. Fourth row, left Mendelsohn; right Toyotomi Hidetsugu (1568-1595). Fifth row: left Hachisuka Yoshishige (1586-1620); right Mendelsohn. Sixth row, left Mendelsohn, 1917; center Mori Motonari (1497-1571); right Mendelsohn, 1917.

Both Kenshin and Mendelsohn are reminiscent of ships more than buildings.

Rotate Hidenaga's two parallel 'horns' upward and the similarity with Mendelsohn becomes apparent.

Even the flick at the other end of Yoshishige's 'blob' is mirrored in Mendelsohn's blob.

Designs with up cut pointed ends reminiscent of Japanese kao drawn with a brush

First row: left, Mendelsohn; right, kao of Bessho Yoshiharu (1579-1654). Second row: center images Mendelsohn; far left kao of Konishi Yukinaga (1558-1600); far right Saito Yoshitatsu (c.1527-1561).

Croquis with flatish, ground hugging, downward sloping, often bent designs

First row two center images Mendelsohn; far left Asai (Azai) Nagamasa (1545-1573); far right Hojo Ujinao (1562-1591). Second row, from left to right: Mendelsohn; Ii Naomasa (1561-1602); Mendelsohn; Naoe Kanetsugu (1560-1620).

Croquis with funnel like or bent, form with jagged or ribbed elements

First row, Mendelsohn to the left and right. Center Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582). Second row, Mendelsohn center, left Oda Nobunaga, right Asakura Yoshikage (1533-1573).

Below, from left: Gyoen Hoshinno (son of Emperor Kameyama, 14th century) kao of 1335; Mendelsohn;Mendelsohn; Hirai Sadatake (16th century).

Croquis emphasizing verticality and angularity, with sharp edges and wedge like cuts and pointed extensions

Mendelsohn left, various Ashikaga Shogun kao on the right. First row: Mendelsohn, Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1436-1490). Second row: Ashikaga Yoshizumi (1481-1511). Third row: Mendelsohn; Ashikaga Yoshinori (1394-1441). Fourth row: Mendelsohn; Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358-1408). Fifth row: Mendelsohn; Ashikaga Yoshinori. The kao here are all from the Muromachi period from the 14th to mid-16th centuries, of the Ashikaga shoguns.

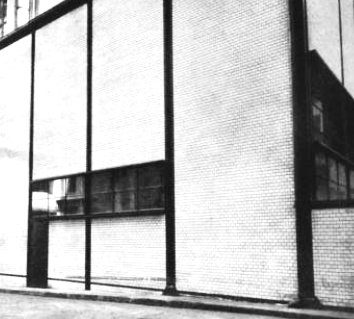

Example of more finished elevation, kao japonisme via the technique of 'elaboration'. Center: Mendelsohn's Skyscraper on the Kemperplatz, Berlin (1922). Note in particular the similarities of Mendelsohn's elevation with the kao to the left. If one looks closely, the parts of the kao find their corresponding sections of Mendelsohn's building. The kao functions wonderfully as a croquis, where exaggerated elements are toned down to the level of realizable construction, and are elaborated upon with greater detail, but the basic idea remains. Left Honda Masazumi (1565-1637); right Hosokawa Tadatoshi (1586-1641).

Roundish organic designs whimsical and fantastic in nature

The Mendelsohn designs are center, to the left and right are Japanese kao. First row: center Mendelsohn pleasure pavilion; left Okudaira Masayuki (1855-1884); right Ashikaga Yoshiharu (1511-1550). Second row: center Mendelsohn pleasure pavilion; left Konoye Iehiro (1667-1736); right Makishima Akimitsu (late 16th century - 1646). Third row: center Mendelsohn pleasure pavilion; left Miyoshi Yoshitsugu (1549-1573); right Date Masamune (1567-1636).

Use of kao as a framing device

Two center images are by Mendelsohn, to the far left and right are Japanese kao. Far left: Otomo Sorin (1530-1587); far right: Hoan Kokei (Kokei Sochin) 1532-1597).

The following are built designs of Mendelsohn, with comparisons to Japanese architecture:

Herrmann & Co. hat factory, Luckenwalde, Germany, 1921

Mendelsohn's hat factory compared with farmhouses, typical of the Tohoku (northern) region of Japan.

Temple and Community Center, Congregation Emanu-El, Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA, 1948-1952

Temple and Community Center, Congregation Emanu-El, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1948-1952 compared with Katsura Imperial Villa, Kyoto. The plan also reminds one of the Bauhaus, which is even more analogous to the Katsura Villa, and it seems Mendelsohn takes from both. While the positioning has been altered, the spatial concepts remain the same: a prominent, frontward projecting main hall, the basic bent building formations, and the square and corridor-like semi-enclosed courtyard areas; all are still clearly recognizable. Like the Katsura Villa, the main building is approached from the side, first passing along a wall.

Pacific Heights, San Francisco, USA, 1950-1951

The Mendelsohn designed Pacific Heights house, San Francisco, 1950-1951. Echoes of Kiyomizu-dera (Temple), Kyoto. The bulky, solid top floor corresponds to the roof of Kiyomizu-dera, and Mendelsohn's outward projecting round bay echoes the corner deck of the temple, shown in the photo to the right. The floor below, the Main Floor, whose floor plan is shown below, with its spacious and wide balcony, corresponds to the 'Kiyomizu-no-butai' or 'stage'-like deck. Like Kiyomizu-dera, the Pacific Heights house juts over an incline with sweeping vistas below, one of San Francisco Bay; the ancient temple, of the whole valley of Kyoto. Exposed pillars support the Mendelsohn designed house, as do wood ones at Kiyomizu. Mendelsohn's design, though more faithful to the Kiyomizu-dera concept, also reminds one of Frank Lloyd Wright's famous Falling Water (Pennsylvania, 1937), which, by the way, was also likely to have been part inspired by Kiyomizu-dera, as discussed by Clay Lancaster in his The Japanese Influence in America (However the main hall of Hasedera Temple (Sakurai, Nara), with its far extending rectangular platform, was probably the more important model for Wright). The photo of the interior shows shoji-like sliding doors and a small nakaniwa style area for plants. The main floor plan also reflects other typical features of Japanese residential architecture, such as its 'engawa' corridor and then balcony combination, a double 'buffer' zone layout, corridor-like balconies on both sides of the dining room, ending with a 'tsuke-shoin'-like corner room whose two sides face the exterior--these are all related features found together in Japanese traditional residential architecture. It is easy to forget just how revolutionary this sort of plan was, compared to traditional Western architecture, where corridors were in the center of a building, branching out to rooms placed in rows along the exterior of a house; and how quintessentially Japanese were modern plans.

Hebrew University, Mount Scopus, Jerusalem, Israel, 1936-1938.

The massive, solid, block-like nature of the university buildings, viewed from the exterior, belies Japanese style features blended within. From the left: a 'sode-kabe' (kimono-sleeve wall) style partition with interior window, somewhat like a scene in a chashitsu (tea house); a large round interior window, also found in tea houses and temples overlooking nakaniwa or corridors; a glass wall-partition with 'koshi' (shoji wood grill) proportioned window panes.

Examples of various Japanese architectural features found in Mendelsohn's works

Other facade treatments, signs, and interior features characteristic of Japanese architecture or culture. Often those elements of plan, facade, and interior design are packaged together in Mendelsohn's designs.

Kao: The Whimsical Parade of the Imagination

Above: Eric Mendelsohn, a variety of imaginary, whimsical project drawings; below, two spreads from a booklet of kao. A similar spirit of Mendelsohn's whimsy and fantasy can be found in kao (no specific parallels intended here). Collections of kao were numerous and republished in the Meiji period, and often in compact pocket sizes.

Bibliography

(under construction)

Hitomi Rihei (人見 理兵衛) and others, publishers (author unidentified). Chajin Kaoso (茶人花押藪), Osaka, 1746.

Kawazu Horai (河津 蓬莱). Zoku Chajin Kaoso (続 茶人花押藪), 1805.

Kohitsu Ryochu (古筆 了仲). Shigan Insho Kaofu (紫巌印章花押譜), Okamuraya Shōsuke (岡村屋 庄助) publisher, Edo, c. mid-19th century, before 1869.

Maruyama Yoshizumi (丸山 可澄 1657-1731). Kaoso (花押藪 7 volumes), first printing 1690, sequel (続編, 7 volumes) 1708; reprints of the combined 14 volumes in the following centuries up to the Meiji era.

Matsuzaki Sukeyuki (松崎 祐之). Koofu (古押譜 6 volumes), 1715.

Nakagawa Toshiro (中川 藤四郎) publisher (author unidentified). Gunken Oofu (群賢押譜) Takemura (武村) version, Kyoto, 1824.

Yashiro Hirokata (屋代 弘賢 1758-1841) editor. Kaoshu (花押集), late 18th - early 19th century.

Yokoyama Kan (横山 寛). Kaoshui (花押拾遺 5 volumes), Eirakuya Toshiro (永楽屋 東四郎) and others, publishers, 1836.

________________________

Uploaded 2023/5/21 - 7/11

Philip Johnson (1906-2005)

From the Ancients to Contemporaries of Japan

or

From Modernist Subtraction to Post-Modern Addition

Yasutaka Aoyama

Modernist Subtraction--the Abstraction of Traditional Japanese Architecture

"Philip Johnson, born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1906, gained a profound knowledge of Japanese building while he was Director of the Department of Architecture at The Museum of Modern Art in New York."

Siegfried Wichmann, Japonisme: The Japanese influence on Western art since 1858 (1981, p.366)

Like Mies van der Rohe, whom Philip Johnson collaborated with, Johnson's early japonisme is characterized by the abstracting of key Japanese architectural principles into his designs using industrial materials, and the shearing away of traditional, identifying markers.

Clay Lancaster, a noted historian of 19th and early 20th century American architecture, who wrote the milestone work The Japanese Influence in America (1966), discussed the clear influence of Japanese architectural concepts upon Johnson's early designs (images from his book are shown below), focusing upon the Rockefeller Guest House in New York City (1950) and the Philip Johnson House in Cambridge, Massachusetts (1942).

The photo of the courtyard garden of the Rockefeller Guest House is very much in a 'naka-niwa' style, and takes from classic Japanese gardening principles. Observe the square stepping stones to cross the shallow pond, the single, sparsely branched tree enclosed by a wall, and the style of open framing on the other sides, all in roughly Japanese 'tsubo-niwa' scale and proportions. The house is relatively narrow and deep, reminscent of classic kyoto city homes, or 'machiya'.

The Philip Johnson House in Cambridge is another case of abstracting (including 'de-roofing') of the most fundamental concepts, and scaling, of a traditional Japanese residence, with its enclosed, walled garden and small street entrance from which the interior may be glimpsed; and its living spaces that are open in continuous fashion to the garden, as in a typical one storey Japanese 'hiraya'. His personal residences seem to have been generally Japanese in conception. Of his house in New Canaan, CT (1949), built several years later, Wichmann notes how "All exterior walls are glasss, creating an open effect comparable to a Japanese house. The simplified ground-plan is like Japanese modular systems." (Japonisme, p. 361)

Elsewhere too, one finds parallels between Johnson's works and traditional Japanese architecture. His idea of a black, glass box placed crossways and overhanging a solid, stone based, larger rectangular structure (below left) seems to echo the same basic concept found in castle 'tenshukaku' design, as in the case of Kumamoto Castle (below right).

Post-Modern Addition, or the Grafting of Contemporary Japanese Architecture

The AT&T Building, Madison Avenue, New York

Not the First Post-Modern Skyscraper

The first post-modern skyscraper was not designed by Philip Johnson and completed in 1984 in Manhattan, but in 1965 in Yokohama, by the Obayashi Gumi's (corporation) architectural team, who came up with innovative modern and post-modern designs throughout the 1960's and 70's. Indeed, it can be argued that post-modernism was born in Japan as the great-grandchild of the Meiji Restoration (a de facto revolution): the merging of traditional Japanese and Western styles, producing the 'wayo-secchu' style as its first offspring; which married to industrial technology produced a more modernist 'machine' style in Japan as a natural consequence; and finally from there a re-uniting with traditional motifs that led to the post-modern movement, from the early 1960's (at the latest) in Japan.

The phenomenal recovery of Japan in the post-WWII period, whose pace quickened in the early 1960's, saw the rapid construction of a variety of original designs, in a country with few building restrictions or community imposed restraints on design compared to Western countries. Innovative and sometimes outlandish buildings sprouted up in cities across Japan, and a new kind of architectural japonisme, based on contemporary designs took hold of architects in Western countries, especially the United States.

James Steele, in his section on 'The Japanese Influence' in his book on Charles and Ray Eames, discusses that widespread phenomenon in architecture; and Philip Johnson was no less influenced by it. It was a japonisme, however, by different means: it was, simply put, a japonisme of addition, of surgical graftings and of elaborations, in contrast with his japonisme (and that of his contemporaries such as Mies van der Rohe) of subtractions and abstractions of Japanese aesthetic principles.

Johnson's skyscraper on Madison Avenue with its 'Chippendale' roof (first the AT&T Building, then the Sony Building, and now called 550 Madison Avenue) is a prime example of that shift in approach, so much so, that we might encapsulate the building's design, and only half tongue in cheek, as a simple formula:

OG(1965) + HE(1963) = PJ (1984)

Where OG = Obayashi Gumi (Corporation 1892- ); HE = Hasebe Eikichi (1885-1960); and PJ = Philip Johnson (1906-2005).

The basic idea, that of tall, extremely slender skyscraper, with a non-uniform window pattern, in beige-like, non-industrial tones, topped with a traditional motif, making the edifice a giant magnification of a more traditional structure, is all present in the design of the Obayashi Gumi's Hotel Empire (presently the library of the Yokohama Univ. of Pharmacy) in Yokohama. This structure was meant to evoke a pagoda, with its roof and spire. It has, when one looks carefully, slight eaves on each level which echo the eaves of a pagoda. The top floor is a panoramic viewing area, as in the case of the Madison Avenue building. But of course it is not a pagoda, and never pretends to be; it has simply utilized traditional elements for its own purposes.

The entrance level of Johnson's design however, is different from that of the Hotel Empire. Instead, it parallels in many ways St. Mary's Cathedral of Osaka, designed by Hasebe Eikichi, a pioneer of post-modern architecture (along with Kikutake Kiyonori and Murano Togo, among others). Hasebe's cathedral, designed before his death in 1960, and completed in 1963, is ahead of its time, yet also reassuring, unassuming, and elegant. Its combination of broad, unadorned surfaces combined with traditional arches and images is more innovative than Johnson's more predictable design, which combines elements of the front and side facades of Hasebe's St. Mary's. In surface texture and color, too, Johnson has faithfully reproduced Hasebe's church. Johnson's lobby is indeed cathedral-like; and further confirmation is gained when one looks inside St. Mary's: even the oversized, geometric floor designs, which lead from the entrance to altar in St. Mary's, are recreated with similar affect inside the Madison Avenue lobby, if reoriented in direction. In St. Mary's, the crucifix is fixed high up hanging from the ceiling, not on the wall of the altar, but more upfront, as if suspended; and due to the backdrop of the golden wall of the altar, the crucified Jesus glows in gold. This effect too, is somewhat reproduced using a glittering gold statue of a Greek god, it seems, in Johnson's design, which is placed on an unusually high pedestal.

To summarize, it is as if Johnson has attached a 'Westernized' version of the 'Easternized' Hotel Empire of Yokohama on the roof of St. Mary's Cathedral of Osaka, and placed it in Manhattan.

Text to be added.

Uploaded 2023/6/2

Afterword

Murano Togo (1891-1984)

Rethinking Post-Modernism's Origins

Yasutaka Aoyama

Murano Togo, one of Japan's most original and internationally under-appreciated architects, also deserves mention here. Murano has been wrongly characterized as an architect without a distinctive style; but this is simply due to a lack of global perspective. More than Hasebe Eikichi discussed above or even Kikutake Kiyonori, it is Murano Togo who perhaps best deserves the title of 'Father of Post-Modernism'.

His Shin-kabuki-za (New Kabuki Theater) of Osaka, shown below, was built, incredibly, in 1958; Charles Moore's iconic Piazza d'Italia, shown next to it, 20 years later in 1978. Murano, in the example below, has played with the forms of a traditional 'karahafu' arch in precisely a post-modernist way, multiplying, stacking, and recoloring them to create a strikingly new facade design. Has not Moore re-enacted what Murano did with ancient Japanese arches, this time with classical Roman arches, playing with those traditional elements in ways that conflict with their original principles of proportion, function, and number -- in the spirit of Murano's work? Or are we to say that post-modernism must utilize only Western, Greco-Roman symbols to qualify as post-modern? If so, it could rightly be condemned as one of the most blatant cases of ethnocentric intellectual chauvinism of our time.

In Japan, modernism was already studied and practiced by artists before WWII; and with the gut-wrenching devastation of nuclear defeat, on to the post-WWII rebuilding of the nation, there was much architectural experimentation going on. Japan was indeed somersaulting through political, social, technological, philosophical, and artistic change at great speed. Imperialism, marxism, existentialism, futurism, modernism, and every possible ideological and aesthetic movement was embraced and attacked between 1925 to 1955. From Taisho democracy to military dictatorship, and from there to the loss of sovereignty and occupation, on to independence and liberal democracy, Japan went through multiple political upheavals and paradigm-shifts as well as splinterings of worldview. America went through economic boom and bust, and its political systems and moral values were challenged, but not overthrown. In more ways than one, America was a more conservative and slower evolving society during that age. Post-modernism did not start in the 1970s in America, but in the 1950's in Japan.

The agelessness (or age-defying quality) of Murano Togo's designs

Murano's buildings often look a quarter to half a century younger than they actually are. Take the two examples below: to the left, the Yahata Library built in 1955 (sadly recently demolished), which reminds us of the Gordon Wu Hall (1983) at Princeton by Robert Venturi; and even more surprising is the Watanabe Okina Memorial Hall, built astonishingly in 1937, but looking something like an Isozaki Arata design from the 1980's! Charles Jencks' omission of Murano (and Hasebe Eikichi) in his numerous editions of The Language of Post-Modern Architecture is one of the major flaws of his otherwise inclusive approach to Japanese designers in his now classic exposition on the rise of architectural Post-Modernism.

Addendum: Classic Precursors of Global Post-Modernism

(Added 2024.6.28)

The structure below to the left, designed by Edgar Cline, was one of the earliest Buddhist temples in Los Angeles, now part of the Japanese American National Museum. Its mix of materials and historical motifs, the manner of its eclecticism and welding of contrasting forms, is much like that of the 'Post-Modern' approach in the years to come, not so disimiliar to the work of Michael Graves (excepting the Japanese features). Note the low relief classical columns in red brick with gold capitals on a limestone surface, mixed with a staggered brick base; combined with an imposing karahafu entrance made of stone rather than wood, conveying a sense of massive heaviness utterly at odds with the thin pasted classical columns. Facing the building, one perceives on the left side a rounded corner, which turns back and 'morphs' into a mainstreet line of shops.

While this seems to be the only building of its kind that Cline undertook, something impelled by design requests of the Japanese American community, it shows, once again, how the interaction of Japanese and Western culture is the key catalyst, seemingly more so than other cultural combinations, in the creation of modern architecture, whether minimalist modern or post-modern historical. For comparison, if we look at early Chinese temples in the United States, we often find simple structures of brick or board, built in the local American manner of construction, with applique type Chinese features at the entrance, and perhaps attachments on the roof; or otherwise, in much more recently built structures, attempts to be faithful reproductions of originals in China. In either case, they are quite un-like the distinctive Japanese-American Buddhist, or Japanese Buddhist in America, designs.

To the right is a classic of post-WWII Japanese kitsch and pastiche: Hotel Daigo, Osaka, an unrecognized masterpiece of its kind, and in danger of destruction. While Venturi claims his was a 'Learning from Las Vegas', it might be argued that certain places in Osaka, and elsewhere in Japan, were, much more than Las Vegas, strikingly 'Post-Modern' in the sense it would come to be known from the 1980's onward. Indeed, many post-modernist designs remind us more of the helter skelter of densely packed, neon-lit Japanese city backstreets of bars, restaurants, and pachinko parlors that are often thought to characterize modern Japan, with its melange of old and new, East and West, gaudy and refined, tall and short, than the facades of Los Vegas, which are relatively speaking, more orderly despite their gaudiness. Charles Moore and William Turnbull's Faculty Club in Santa Barbara (1968), for instance, which Jencks describes as an "ambiguity of spatial cues juxtaposed with traditional signs---tapestry, neon banners" and calls "typically Post-Modern" (The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, 4th edition, 1984, p. 125), is almost a streamlined stage set of such an alley in the Osaka or Tokyo of the 1960's. Its interior even seems to echo the baroque overpasses with their octopus-like multiple stairways that envelope the intersections and railway stations of Japanese cities. A more recent example might be Jon Jerde's Universal Citywalk, Universal City (1993), which might be also described as a sanitized version of Osaka's Dotonbori, in the style of its helter skelter with its large athletic figures or animals plastered to the facades of buildings with elements of them extending beyond the surface of the building.

This argument could be pursued much further, which we will leave for later. The jarring collision of shapes, modern and tall, next to traditional and short, that characterizes various post-modern works, such Ralph Erskine's Bryker Wall on the outside (1976), also reminds us, despite its dominant use of brick, of the typology of Japanese downtown streets in post WWII Japan; so too, does the "bizarre and 'ugly' usage" of overlapping historic ornament in Venturi and Short's Headquarters Building for the North Penn Visitng Nurses Association (1960), to raise just a few more examples.

These examples provide two possible secondary influences, other than the exemplary works of Murano Togo or the usual rationale of post-modern inspiration, i.e., kitsch architecture in post-WWII Japan (one which Charles Jencks suggests by placing such an image on his early cover of the Language of Post-Modern Architecture); and another which has not been considered by architectural historians---Japanese Buddhist temple architecture in America.

Below: Jencks book cover with the Takeyama Minoru designed Nibankan in Shinjuku, Tokyo (1970, with exterior supergraphics by Awazu Kiyoshi) followed by some additional examples of kitsch architecture of the Venturi-lauded type. Besides Mori Wajin's much publicized Cat House in Murayama, Yamagata (2009) and the Kishi Station in Wakayama (2010), which was not only shaped like a cat but whose official station master was a cat called 'Tama', a variety of large outdoor cat figures and structures existed in Japan from the 20th century---thanks to the strong tradition of the 'maneki-neko' with its beckoning paw, which reaches forward, not to mention the popularity of 'Hello Kitty' (Ishiyama Osamu's Gen-an (1975) must also be considered when evaluating this kind of face-as-facade type architecture). Despite this, the celebrated German example of Venturi style Post-Modernism which soon followed in the footsteps---pawsteps of these Japanese examples, Tomi Ungerer and Ayla Suzan Yöndel's Kindergarten Wolfartsweier (2011) in Karlsruhe, Germany, is often discussed with no mention of its Japanese architectural precedents nor the strong kitsch plastic art tradition of what we will call here the 'Maneki-Neko Bunka' ('Welcoming-Cat Culture') of Japan.

Kindergarten Wolfartsweier photo: www.presse.karlsruhe.de.

________________________

Uploaded 2024.6.2. Under construction, preview

Robert Klemmedson (1921-2010) and his Generation of 'G.I.s'

Seeing Japan after WWII during the Occupation

An Architectural Japonisme Refreshingly Honest and Open

Yasutaka Aoyama

Robert Klemmedson was a decorated WWII pilot, experiencing live combat with Japanese Zero fighters, both shooting down and being shot down over the Pacific. He was sent to Japan during the Occupation, and his contact with the culture would have a lasting influence on his architectural design. That was the case for many other dynamic and creative personalities, both well-known and not so as Klemmedson, who as G.I.s would latter becoming artists, cartoonists, writers, architects, and entrepreneurs. This shared experience by thousands of Americans, who would have otherwise probably never have visited Japan, may be considered one of the key factors for the 'Japonisme Renaissance' after WWII in the 1950's, discussed in 'Literary Japonisme' on this website.

Despite being bombed and their nation devastated, the attitude of the common populace in Japan was quite friendly towards American soldiers after the war, which is sometimes hard for those who were not part of the occupation to understand. It was that good naturedness and the high spirits of the Japanese people and their unique culture, experienced first hand, that was to have an impact upon Americans which may have been greater than that of the late 19th century European japonisme movement, which was mainly an influence through imported artistic media and not direct contact, and most likely would not have had such a positive artistic influence if there was no emotional connection involved, beyond and besides art itself. The following is from 'Bob Klemmedson Profile' by Tom Jue in the Sacramento Valley glider association, Windsock Newsletter (May 2008, p. 12), which gives some inkling of those hospitable and unexpected encounters:

"After Japan’s surrender, the Army sent Bob to Japan to assist in the occupation. Bob flew reconnaissance missions while he was in Japan. Amid all this devastation, there were also lighter moments shared by both sides. Several weeks after Bob landed in Japan, he became a transportation officer. He was enamored with a particular brand of Japanese beer. Pursuing this, he drove the streets of Tokyo in his truck, showing this beer bottle to the residents. They would acknowledge and point their fingers with a “that way” direction. Eventually Bob ended up at this beer warehouse! Bob and several of his buddies were able to load up the truck full of beer and brought it back to the barracks to share with his friends. This is the story Bob told me. Here were people from warring nations who had bitter memories of fellow combatants, friends and families killed as a result of battle with one other. In contrast, shortly thereafter in peacetime, they treated each other with hospitality. It was a different era."

Klemmedson, unlike many other modern architects was open regarding the Japanese influences on his design. He actively sought to emulate traditional Japanese architecture, and was not afraid to incorporate traditional Japanese roof forms as well. As can be seen from the example of his 14 Maybeck Twin Drive house shown below, were we to replace his roofs with a flat top or otherwise different shaped roof, we would instantly transform it into more typical 'modern architecture', reminiscent perhaps of an Utzon or Neutra, to be treated so by architectural historians---thus unidentified with Japan---despite the exteriors, interiors, the garden, and the basic inspiration of the design all retaining their strong Japanese character.

Klemmedson thus provokes us to question the veiled assumptions behind appraisals of architectural worth and distinction in modern design criticism: despite all its abstract arguments, when boiled down to its core, is based upon the single criterion of recognizability, or rather the non-recognizability, (i.e. non-identification, non-categorization in an obvious sense) into particular historical or cultural style, and is not based upon pure quality of design and construction regardless of style---which it ought to be---were it something pursuing an estimation of essential merit.

14 Maybeck Twin Dr, Berkeley, CA, 1959

Often said to be inspired by Katsura Imperial Villa of Kyoto, the house was in the Alaa Mansour (professor at the University of California at Berkeley and head of the naval architecture and offshore engineering department) family for more than 4 decades (photo credits to be added).

Ford House, 1064 Via Alta, Lafayette, CA, c. 1959

Known as the 'House of Balconies'. Skillfully incorporating conceptions of light clean, airy woodwork structures found with rough, natural stonework of Japanese country houses, such as in flood prone areas. Japanese influence is so widespread and an ingrained part of modern California design that it is indistinguishable in many cases to Californians who see it simply as 'Californian'. (Photo credits to be added.)

Next, a few photos with captions from the Windsock Newsletter: The Valley Soaring Association Journal, May 2008, Special Edition, dedicated to Klemmedson. To the left is one of Klemmedson's better known works, featured in Sunset Magazine. Here again his design incorporates various Japanese architectural ideas, such as a garden pond which enters into the building (in California quite naturally a swimming pool instead). This was a feature of 19th century sukiya style inns and homes, and transmitted to modern architectural designs in Japan, the best known probably those of Horiguchi Sutemi (1895-1984)---e.g. his Okada House (1933) and his Chinchiriren (1944); and in the same year in a more traditional style, the Shiskunshien, by Kitamura Sutejiro, enlarged in 1963 by Yoshida Isoya.

Klemmedson shows us that American architects can successfully incorporate Japanese traditional styles that are recognizably so, in a way that is difficult to do without criticism among Japanese architects today, despite there being no problem with constructing Anglo-American or Germanic vernacular styles in Japan.

While many fine 'Japanesque' houses have been built in the United States, unfortunately, many of the more spectacular ones dating from the early to mid 20th century have been torn down, whose images remain only in books such as Clay Lancaster's The Japanese Influence in America (1963).

________________________

Uploaded 2024.6.5, under construction

Preview

Paul Thiry (1904-1993)

Japanese Harmony and Proportion

In the 'Father of Architectural Modernism in the Pacific Northwest'

Yasutaka Aoyama

Text to be added.

The above is from Hiroshi Emoto, 'Japonica in Architecture: Origin and Semantic Pluralism' JTLA (Journal of the Faculty of Letters, The University of Tokyo, Aesthetics), Vol.45, 2020. These are the kinds of photos, revealing of an architect's personal fondness for Japanese design and culture, that are usually not included in books, articles, and websites which purport to introduce a reader to modern architecture or a particular modernist designer's work.

The following is an elegant yet unassuming, harmoniously composed and refined example of Thiry's Japanese influenced architecture in one of Seattle's most upscale residential enclaves, 'Windermere'.

6120 Northeast 57th Street, Seattle, Washington

The Joel M. Pritchard Library in Olympia, Washington, displays the proportional relationships of Japanese religious architecture in its veritical layering of base, glass wall, columned eaves, roof height and widths. Connect the jutting eaves and the rectangular block above with curved (i.e. dotted) lines, and magically a modern style Japanese Buddhist temple appears, of the kind that can be found scattered across not only Japan, but also in America.

The Joel M. Pritchard Library, Olympia, Washington

The Haiseido, Iga, Mie Prefecture & the Lewis and Clark College Flanagan Chapel, Portland, Oregon

Oblong stone marker with writing to the right of the Haiseido vs. oblong stone marker with writing to the left of the Flanagan Chapel; flowering cherry trees to the left of the Haiseido, contrasted with the flowering tree to the right of the Flanagan Chapel in the photo above it.

Other projects of Thiry to be discussed: his Ellensburg cabin (in relation to Shinto shrine architecture) and other residential designs. Also Thiry's designs considered in light of modern Japanese architecture built before Thiry's. Finally, a discussion as to who deserves the title of 'father of modernist architecture in the Pacific Northwest'---Thiry, or Minoru Yamasaki.

________________________

Uploaded 2024.6.6, under construction

Preview

Harwell Hamilton Harris (1903-1990)

"Japanophile" Extraordinaire

A Case Study of Reality Unconfronted: Posterity's Avoidance of the Obvious

“The Japanese house most satisfied my liking for immaterial form,—for space. It did not displace space; it marked space, it shaped space. And the materials of Japanese building—hardly more than thin lines and flat planes—were arranged to effect rhythm, rhythm without mass.” ---H. H. Harris (in Harwell Hamilton Harris by Lisa Germany, Univ. of California Press, 2000, p. 33-34)

Various self-evidently Japanese influenced designs and interiors, often complete with Japanese furnishings, to be examined, contrasted with the surprising silence regarding that influence by contemporary architectural journals and later commentators, excepting Harris himself and the noted architectural historian of the American bungalow style, Clay Lancaster, who refers to Harris as the "Japanophile Harwell Hamilton Harris" (1963, p.171). While training for an architectural career during the 1920's Harris spent his spare time poring over books on Japanese building in the Los Angeles Public Library." (Lancaster, 1963, p. 179). One of Harris' favorite possessions was a byobu screen illustrating the Tale of the Genji. Nevertheless, much like the case of Le Corbusier, the more overwhelmingly significant that influence becomes, the less it is touched upon by the doyens of the modernist intellectual establishment.

Only very recently has that shown any change, thanks to the silently accumulating body of academic documentation that modernist architects like Harris indeed were deeply influenced by Japan. Christopher Long, at the University of Texas, Austin, in June of 2023, writes, regarding Harris, after discussing the Japanese aspects of his Fellowship Parkway house:

"In his subsequent works, Harris would often reference Japanese forms—in the 1939 Blair House, for example—employing screens, a penchant for natural materials, and a pronounced formal modularity. What stands out even more is his interest in the play of light, which to my eye often has about it a Japanese sensibility. Harris was sensitive to fostering light patterns—or better, maybe, oppositions between light and dark, a long view and a truncated one, and the notion of pure subdued light versus shadow and patterning—all present, for example, in classic Japanese tea houses. Many of these mannerisms remained in his work, even in his latter periods in Austin and Raleigh, where he spent his final years." ('Asian Influences and the Rise of Southern California Modernism', Nonsite.org, afliated to the Emory College of Arts and Sciences, Issue 43, June 16, 2023. At www.nonsite.org.)

The Lowe House, 596 Punahou Street, Altadena CA (1934)

The Harwell Hamilton Harris House, 2311 Fellowship Parkway, Los Angeles, CA (1935)

"Almost as Japanese as the homes of the Japanese themselves is the small house architect Harwell Hamilton Harris built for his own use in 1935 on a hillside in Fellowship Park, at the northeast corner of Los Angeles. ... All but the end posts are reinforced by traingular braces, a device illustrated in Morse's Japanese homes. ... The Japanese folding screen is a necessary item for providing privacy when the shoji are removed during the summer months." (Lancaster, p. 179)

Loeb House, 127 Lonetown Road, Redding CT (1949)

Bibliography (under construction)

Germany, Lisa. Harwell Hamilton Harris. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 2000.

Long, Christopher. 'Asian Influences and the Rise of Southern California Modernism' Nonsite.org (Emory College of Arts and Sciences), Issue 43, June 16, 2023. At www.nonsite.org.

________________________

Uploaded 2024.6.10

Preview

Vladimir Ossipoff (1907-1998)

A Tropical Blend of Japanese Craftsmanship and Design

In the Making of the 'Hawaiian Modern'

Vladimir Ossipoff, recognized as one of Hawaii's foremost modernist architects, was born in Vladivostok, Russia. His father became a military attaché at the Russian Embassy in Japan, where the Ossipoff family moved to in 1909. According to the University of Hawaii Library site for the Ossipoff's papers, by the time Ossipoff was ten, he was well-traveled, moving between Tokyo and Petrograd. Traditional and modern Japanese architecture was a familiar sight to him and as a boy in Tokyo, as well as architecture by foreign architects in Japan, such as Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel. Such experiences were probably important factors in his receptiveness to modern ideas of architecture, despite at Berkeley where he studied being dominated by the French Beaux-Arts system and its stylistic tendencies. Moving to Honolulu after graduating, he soon established his own practice, and as Anya Ventura writes in 'The Architect Who Brought Tropical Modernism to Hawaii' (2019.1.9, artsy.net): "Fluent in Japanese, Ossipoff collaborated with Japanese craftsmen, whose precision he exulted in.” Or as Laura McGuire (University of Hawaii) explains in 'Vladimir Ossipoff: A Brief Biography': "Ossipoff’s Hawai‘i modernism used many Japanese-styled approaches to design and construction." ('Vladimir Ossipoff Architecture Papers at the University of Hawaii Library' https://guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu). Following are some quotes from the same article at the University of Hawaii Library website, focusing on the Japanese aspects of Ossipoff's architecture:

Regarding the Liljestrand house (1952):

"Ossipoff employed the ample supply of Japanese carpenters on the islands to create interior woodwork with Japan-derived joinery, giving the house a subtle air of Japonisme, but one that was integrated with midcentury modernist formal and spatial languages."

Blanche Hill House (1961):

"...Ossipoff designed a staggered plan of rooms that drew subtly on traditional Japanese palace arrangements and expressed his concept of the “living lanai” – in which lanais formed the primary social centers of the house."

Davies Memorial Chapel at the Hawai‘i Preparatory Academy (1966):

"Japanese idioms often drawn from Edo period designs like teahouses were a prominent part of Ossipoff’s work in the middle 1960s and he explored the aesthetic potentials of many local materials in his works, using the beauty of sanded and finished monkeypod wood and exposed lava rock aggregate in poured concrete surfaces."

Outrigger Canoe Club (1963):

"As in the commissions described earlier, his approach strongly resonated with Japanese Edo period architecture and garden design. Although the club certainly did not look “Japanese” on its surface, the lessons of Japan were clearly present in Ossipoff’s guiding architectural logic. The building’s highly ordered, rectilinear geometries, its flowing spaces of the open lanais, and its carefully curated series of views of various interior plantings and spatial adjacencies was of a distinctly Japanese character."

The following is a quote from 'Time, Place and Culture: An Interview with Dean Sakamoto on the Work of Vladimir Ossipoff, part 2' by Build LLC, architects and designers, posted 2017.9.27.

Goodsill House (1954):

"The Goodsill house was intended to be a starter house and was designed like a Japanese farmhouse. Despite the fact that the owner, Marshall Goodsill, went on to become one of the most powerful attorneys on the island, he couldn’t leave the house. He could have built whatever he wanted. When he died, he bequeathed the home to the Honolulu Museum of Art." ----Dean Sakamoto, architect and editor of Modern Hawaiian: The Architecture of Vladimir Ossipoff (Honolulu Academy of Arts and Yale University Press, 2007).

________________________