Japonisme Insights into Modern Painting II

モダンアート(絵画)のジャポニスム II

Image: Toyohara Kunichika, 1884 御台所於政ノ方(中村福助)/日吉将軍高吉(市川団十郎) その他. Kunichika is one of those unsung masters of the ukiyo-e print who deserves to be included among the masters of modern art.

From the print version of The JAPONISME MUSEUM Newsletter, January 2021 'Exhibiting Japonisme'

Transferred from the page 'The JAPONISME MUSEUM Newsletter' 2024.8.23

抽象芸術に潜む茶道の「触感的」美学

Tea Ceremony Aesthetics in the Texture of Abstract Art

Cross-cultural & Trans-media Influence

ジャポニスム・ミュージアム展示パネルから / From The JAPONISME MUSEUM exhibit panel

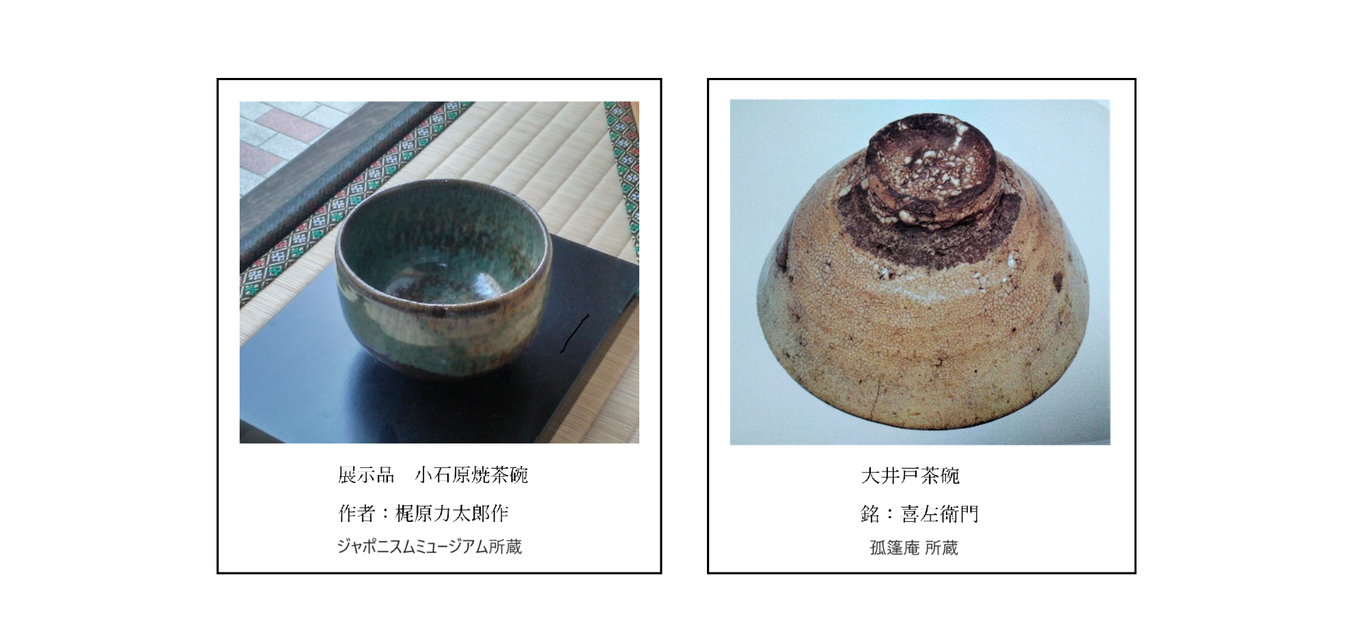

この空間は、茶道具と抽象芸術を一緒に楽しむ世界一小さな「お茶の間」かもしれません。茶碗や棗などの茶道具と、抽象絵画などのモダン芸術とを比較して、両者をより深く鑑賞し理解することが目的です。当館の展示品は、その都度に置き換え、古い物も時には展示しますが、ほとんどは茶道具として珍しくはないものです。それでもある陶芸家の手作りの作品に違いはありませんし、そういうものでも近・現代抽象芸術と似通う側面があり、比較するための実例として充分に役立ちます。

茶碗や茶入れなどは、立体的な三次元の形のものに対して、絵画は主に平面的で二次元のものです。しかし、想像力を少し働かせれば、同じようなものとして考えることができます。茶碗を円筒として考え (底はいったん無視して)、その円筒を一カ所縦に切って平たくすれば、横長のキャンバスに描かれた抽象画のように見えてきます。また、抽象画も横に少し伸ばしこれを円筒形に曲げて両端をつなげれば、茶碗のように見えてきます。

このように、異なる芸術媒体である釉薬をかけた「茶碗」と、絵具を塗ったモダン「絵画」は、同じように視感することができるようになります。これによって、両者を同じ感覚で楽しめるようになり、その美学的類似性にも気づくことでしょう。

これを抽象芸術に潜む茶道の「触感的美学」、とジャポニスム・ミュージアムでは呼んでいます。抽象画は、三次元のものを二次元の表面にいわば変換するだけではなく、抽象画はそれ自体が、つまりキャンバスと絵具という材料そのものが、画として成り立つ存在とされています。これはちょうど茶道具を鑑賞するアプローチと同じなのです。

また茶碗は、手に取らなくても鑑賞できますが、常に「もし手に取ったら」という潜在的意識が働いて眺めているわけです。そういう意味で「触感的」であり、抽象画もテクスチャーを意識し、触れたい気持ちにさせるところがあるといえるでしょう。

アイデア・概念が作品に含まれていても、論理よりも感触でそれを伝えようとするものです。そして茶碗に名前をつけるように、抽象画も、画題が作品と関わりあってもよいわけですしなくてもよいのです。なぜなら「他」との関係を必要としないからです。

この一見異なる二つのもの、茶道具の「茶碗」と抽象芸術の「絵画」の意匠が、何らかの関わりがあるとすれば、これは芸術媒体(art medium)の枠を超えた、ある媒体(陶芸)から別の媒体(描画)への波動と考えられるでしょう。トランスメディア(trans-media)もしくはクロスメディア(cross-media)の影響ということになります。それに加え、異文化を横断する影響として、クロスカルチャー(cross-cultural)でもあるということになります。

文化の異なる二者の接触がある場合、どちら側からも何かが伝わることは言うまでもないはずですが、多くの方はそうは感じていないかもしれません。地球の重力のように、一方的にこちらが絶えず受け身の立場にあると思い込むような文化史のシナリオのみを聞かされているところはないでしょうか。これまで避けられてきた日本の工芸と世界の抽象芸術との類似性や関係性を問うディスカッションも必要であると思います。

Following section revised 2024.8.25

マークトビーの抽象画と茶道の「触感的」美学

(ジャポニスム・ミュージアム展示パネルから)

抽象画家マークトビー(1890年-1976年) は、米国の初期抽象芸術の中心的な存在でありながら、日本ではあまり知られていない。そして抽象画家の中では、日本の影響を認めた稀なる一人といえる。中国で書道を学び、日本の禅寺で修行した彼の作品には、「Space Ritual」(1957年) という墨絵のシリーズもある。パフォーマンスアート*の発明家とされるフランスのジョルジュ・マテューはトビーを讃え、「ヴォルス(ドイツの抽象画家)と、トビーの登場によって、全ての芸術的記号は作り直さなければならない」(Colette Roberts, Mark Tobey, 1959) と断言するほどであったが、これは芸術家が贈る最上の賛美であろう。

美術評論家のミシェル・タピエは、トビーを抽象絵画の発展にとって不可欠な存在であったとする(Un Art Autre, 1952)。トビーの重要性を物語る一例として、抽象芸術界を席巻したあのジャクソンポロックは、まめにトビーの画を画廊に見に行き、1944年にトビーによる「Bars and Flails」を友人に見せられ、それがインスピレーションとなって彼の有名な絵「Blue Poles」を制作したとされている。トビーのテクニックに大いに感銘を受けたことを、ポロック自身が言い残している (Priscilla Long, 'Mark Tobey paints the first of his white style paintings in November or December of 1935', 2002)。

トビーは面識も広く、視覚芸術にとどまらず作曲家ジョンゲージや陶芸家バーナードリーチを含め多くの芸術家と親しかった。1940~50年代、トビーこそがアメリカ抽象芸術の筆頭だと考える者も少なくなかった。また、フランスの『抽象絵画辞典』(Michel Seuphor, Dictionnaire de la Peinture Abstraite, 1958)には、「クレーやトビーの、内に秘めたるものが、他のアーティストよりもわれわれの奥深くまで届く・・」と記してあるのも、そうしたクレーのようなモダン絵画の巨匠の一人と肩を並べる芸術界に名声が轟いていたトビーであったからだ。

そのトビーが、芸術の発展のために今までヨーロッパの虜となっていたアメリカの芸術家たちに、アジアに目を向けるように説いたのである。「トビーの伝記作者全員が、彼の創造過程において、東洋が果たす役割を強く主張する」と、『マークトビー』の作者コレットロバーツは言う。だがそのトビーでさえ「茶道具」の抽象芸術との関係には触れてないようである。彼のみならず芸術家にとっては、真の種明かしは禁物であるからかもしれない。

*日本のアヴァンギャルド芸術グループ「グタイ」のパフォーマンスアートを含め、これらは実は日本の伝統的な大筆書道に遡るものとして見据えることができよう。書道と抽象画の関係に関しては、Kakei Nanako (筧 菜奈子) 'Oriental Calligraphy in Jackson Pollock: A Study on Formation of Black-Paintings'. Aesthetics, No. 21, 2018, pp. 45-54 (The Japanese Society for Aesthetics) を参照。

マーク・トビー (Mark Tobey 1890-1976)

_______________________

Uploaded 2024.8.30

ジャポニスムミュージアム、シュールレアリスムのジャポニスム常設展(2021年から)

MODERN SURREALISM / 後期シュルレアリスム

ルネ・マグリット

「デペイズマン」のジャポニスム

René Margritte and the Japonisme of ‘Dépaysement’

ベルギー出身の画家 ルネ・マグリット (René Margritte 1898-1967) は、サルバドール・ダリと肩を並べる屈指のシュールレアリストである。そのオーバーコートと山高帽を身につけた顔が緑のリンゴで覆われた自画像「人の子」は、あまりにも有名で、世界の誰でも見たことのあるアイコニックなイメージとなった。マグリットがキュビスムや未来主義、ジョルジョ・デ・キリコの影響を受けたことはよく知られているが、その手法「デペイズマン」、つまり物を異なる環境に置き換える発想は、既に日本で長らく浮世絵師が用いていた作法テクニックの一つであった。超現実主義的な発想に関してはマグリットに負けない奇抜で斬新な図像を表した一世紀も前の三代歌川広重 (1842-1894)のことは、今の現代美術界ではほとんど語られることはない。だが、広重の奇妙な絵「買運気十八番之内」は、マグリットのような自画像のイメージの先駆けといえるであろう。マグリットが「人の子」を作成した同1964年に、三代広重の意図を知るかのように似た3枚の絵を描いている。マグリットと広重の絵を隣り合わせに置くと興味深い類似性が浮かんでくるのである。それぞれの絵が対を成し、六枚揃って、もとより一つのセットであったかのようにまで見えてくる。

ルネ・マグリット 1964年

三代歌川広重 1880年

最初にマグリット左側の La Grande Guerre Façades (世界大戦、大戦争のファサード) と、広重の三枚続の左一枚。マグリットの、日傘を持つ婦人の手のありさまと、広重の、杖を持つ笠をした人物の手のありさま、その類似性。両者の色配分は異なるものの、アクセント色として紫色が主となっていることにも注意。そしてもちろん、両者のだだっぴろい帽子と歪み具合がなんとなく似ている。

次にマグリットの三作の中央にある L'Homme au Chapeau Melon (山高帽の男) と、広重の中央の一枚。「人の子」と同じく山高帽をかぶった男性が描かれている。鳥が男性の顔の前に飛んでいる。これと中央の広重の人物の顔を覆っている物を比べると、鳥の羽と俵のような藁の細かく毛のような性質が類似する。また、黄色の色彩が両者の絵で強調されている。広重の俵に対して、マグリットの鳥の羽は白いが、ベージュ色のネクタイでその形跡を感じる。

最後にマグリット右端の La Grande Guerre(世界戦争、大戦争) と、広重の右一枚。マグリットの「人の子」の上半身のみを描いたこの作品の構図の方が、広重のこの絵、顔を隠す円形の印がある非常に似た青いリンゴ色の紙のものと、より近い。真っ黒の烏帽子の丸さと大きさが広重のイメージの中で強調され、「山高帽の男」のチャーコールグレイの渋い服装と対照的に、この男性の際立って黒い山高帽とコートはそれを反映しているようだ。また、「山高帽の男」の絵に無いこの絵の特徴的なシャツの襟の角は、広重の右一枚のみに見える角の立つ白い結び布や肩衣 (かたぎぬ) の模様と、密かに共鳴するようだ。

三代広重の絵は、マグリットが説いた文字通りの「目に見える思考」、不可思議なイメージであり、マグリットと同様に不可思議な題名を持つ「言葉とイメージ」の追求である。マグリットのいう、自身の絵がもたらす「隠れてしまうものを見たいと思って人は見ることができない事象に興味を持ち、この隠されたものへの激しい関心」は、広重の作品にぴったり当てはまる言葉でもある。広重は明治の激しい変遷を目の当たりにして、マグリットのように以前の「常識を覆す」ものを多く描いている。ここでは、マグリットと三代広重の作品を僅かに比較する展示場所しかないが、広重以外の作品にも、例えば空高く浮く滑稽な人と物の群など、マグリットの造出したイメージには、日本の浮世絵師が先駆けて描いた似通う図像が幾つもある。

_______________________

Uploaded 2024.9.25

以下は一階常設展示スペースの「コラージュという芸術形態の発明」(2021年以降から)に基づく

マティスとコラージュのジャポニスム

The Japanese Invention of Collage as Art Form

The Example of Matisse

"Une fois l'œil désencrassé, nettoyé par les crépons japonais,

j'étais apte à recevoir les couleurs en raison de leur pouvoir émotif."

Henri Matisse (in 'Le Chemin de la couleur', Art présent II, 1947, p. 203)

「日本のクレポンでふさがれた目が一度浄化された後は、

私は、色彩というものをその感情的パワーに応じて享受する準備が整ったのである。」

アンリ・マティス (色彩の道『現代アート II』1947年 203頁)

日本のクレポンとは、ちりめんの絵のことで、明治時代に広く別摺の絵だけでなくちりめん本としても数多く出版された。大判の浮世絵をちりめんの紙に縮めてプリントする。元絵の60%位に縮小するため、色彩も圧縮されて強くなる。こうしてマティスは日本の絵の要素を自らの絵に取り入れたのである。

フランスの画家アンリ・マティス(1869~1954)は、フォーヴィスムの指導者的な存在として有名である。その絵ば、強く明るい色彩効果、太い明快な線描写、平坦な構図――これらの一体化した画法が特徴的である。マティスはG.モローに師事し、後にセザンヌ、スーラなどの影響も受けたとされている。マティスが抱いた浮世絵版画やちりめん絵への関心とその収取は、既に研究されており、マティス研究者の間では知られているが、以下にあるような明治期の版画との関係を示す具体的な比較は、当館展示独自のものである。

マティスは、様々な意味で、日本の明治期の版画の要素を取り入れている。マティスの画法の特徴とされる、太線と色での画面の区切り、そして異なる線形を調和させ、光や色に頼らず線形を活かして奥行を表す、などといった手法は、既に江戸、特に明治期の版画絵師によって見出されていた。当館一階にある展示(以下の写真)の他、二階中央の壁一面には、そうしたマティスの幾つもの作品のイメージと、明治期の版画を隣り合わせに、解説されている。

版画や前述の張り交ぜ屏風の手法以外にも、江戸・明治の日本では、コラージュ的な工作が広く庶民の間で活かされていた。その一つが「ちぎり絵」で、これはまさに、コラージュの一種であり、江戸・明治の折り紙・切り紙(色紙などにも貼り付けていた)とともに、日本文化に根付いていた「絵遊び」の豊かさを物語っている。ちなみに、マティスは晩年に「切り紙絵」をよく制作していたのである。

上段:アンリ・マティス / Henri Matisse

左から(複写縮小図):1「Les Marguerites(ヒナギク)」1939年。2「Intérieur Jaune et Bleu(黄と青の室内)」1946年。3「アンリマチス展」国立博物館表慶館ポスタ---部1951年、切り紙式の絵。4「Odalisque à la Robe Rouge(赤いローブのオダリスク)」1937年。5「La Robe-Violette-et-Anémones(紫のローブとアネモネ)」1937年。

下段:長谷川貞信、三代歌川豊国、豊原国周

左:長谷川 貞信 / Hasegawa Sadanobu 仮題名「障子末広竹」木版画 明治初期(1870年代)。貞信の図面の区分的構造の発想は、斬新に見えても、江戸時代から引き継がれた作法で、その基本コンセプトはさらに古い、異なる書画・紙素材を敢えて貼り混ぜる屏風や襖作法に由来するといえる。上段、特に左二枚のマティス画は、この貞信の構図アプローチに似ているのが分かりやすいに思われる。

中央:歌川国貞 (三代豊国) / Utagawa Kunisada「白拍子さくら木せいたか坊」木版画 安政5年(1858年)。さすが国貞であると思わせる作品。違った形・向きの肖像画が張り付けられているのは、まるで電子回路の図形のようで、SF映画、『マトリックス』に出てくるような別世界を感じさせる絵ではないか。マティスの絵にある、抽象的な模様の壁紙・などの背景も、ある意味で似たような効果をもたらす。

右:豊原 国周 / Toyohara Kunichika「俳優舌師あたりくらべ」・「小猿七之助権之助蝶つかひ 河原崎咲松、 岩藤の亡霊 尾上菊五郎」木版画 明治5~6年頃(1872~1873頃)。国周は国貞の門人であった。様々な角度や形を色分けし、切り貼りされたかのようなこの手法を、上段の中央と右のマティスの絵と比較すると、興味深い類似点が見えてくるであろう。

Addenda in English and French

Albert C. Barnes, noted American art collector and critic

‘MATISSE AND THE JAPANESE TRADITION’ from The Art of Henri-Matisse, Barnes Foundation, 1933, pp. 57-64 of the 1978 (4th) printing.

“The principal and most direct Oriental influence upon Matisse seems to have been that of Japanese prints. Two circumstances probably explain this influence: first, Matisse is by nature a decorator and a colorist with a predilection for strange colors and bizarre combinations; second, at the beginning of his career, Japanese prints, screens, and fans were the vogue in France, and had been drawn upon by many of the most important artists of the nineteenth century for decorative elements which became firmly embedded in the impressionist and post-impressionist traditions. Actual Japanese prints and fans are frequently reproduced in the work of Manet, Whistler, van Gogh, and many others; and decorative features characteristic of the Japanese abound in Degas and Gauguin, and occur, though less frequently, in Renoir, Cezanne and their contemporaries. This was a genuine assimilation of the fundamental plastic principles of the Oriental tradition; it swung away from Courbet and his antecedents and introduced the Oriental element into the art of the era established by the painters of about 1870. It was into this congenial environment that Matisse was born, and it was to the Oriental strain that his own psychological temperament most naturally responded.” (p.57-58, bold added)

Pierre E. Schneider, leading Belgian/French art historian, known for his "dominant monographs on Matisse" (Dictionary of Art Historians, L. Sorensen, ed.) and book on Manet, as well as writings on Modernism

'Enfin le japonisme...' (Chapter 5) from Matisse, Paris: Flammarion, 1984, p. 121-135.

"Le Japon, dont l'influence, venant s'ajouter à celle de Gauguin, fut déterminante pour le style du nabisme, comme pour celui de Toulouse-Lautrec, aurait dû, en toute logique, constituer le lieu commun entre Matisse et le groupe formé par les amis de Maurice Denis, qui dans sa préface au catalogue de la IXe exposition des peintres impressionnistes et symbolistes chez Le Barc de Boutteville, en 1895, attire l'attention sur 'le japonisme, ce levain qui peu à peu envahissait la pâte'. Matisse, de son propre aveu, en a subi l'attraction. Dans sa lettre à André Rouveyre sur les arbres, il rappelle ce que fut pour sa génération la tentation du japonisme: 'On ne regardait pas le Louvre pour ne pas se foutre dedans, c'est-à-dire perdre sa route. Mais on regardait les Japonais, parce qu'ils montraient de la couleur.' " (p. 121, bold added)

("Japan, whose influence, in addition to that of Gauguin, was decisive for the style of Nabisme, as it was for Toulouse-Lautrec, did logically, constitute the common ground between Matisse and the group formed by the friends of Maurice Denis---who in his preface to the catalogue of the IXth exhibition of impressionist and symbolist painters at Le Barc de Boutteville, in 1895, drew attention to "Japonisme, the leavening that, little by little, permeated the substance (‘invaded the dough’) [of our artistic activity]". Matisse, by his own admission, was attracted to it. In his letter to André Rouveyre, discussing trees, he recalls the temptation of Japonisme for his generation: 'We avoided looking at the Louvre [pieces], so as not to get messed up---that is to say, not to lose our way. But we did look at the Japanese, because they showed us color.' ")

See also Klaus Berger, Japonisme in Western Painting from Whistler to Matisse, Cambridge Studies in the History of Art, Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp.313-316.

_______________________

赤の台頭

浮世絵が予示した油絵の色彩動向

鮮烈な色分けと切れるような区分

マティス、ゴーギャン、 ギヨマン、ドラン

周延、広重三世、吟光、玉英を例に

下の写真は当館一階の展示、その最上部から:

鍋田 玉英 Nabeta Gyokuei 「瀬戸川製紙場真景」(三島市)木版画 明治期 (19世後半) 。玉英(1847-没年不詳)は、楊洲周延の門人、作画期は明治10年から明治35年にかけてで、この絵では、製紙工場と富士山を描いているが、全景と富士の背景を真っ赤に色づけしている。また、工場や産業の生産過程を絵の課題にし、抽象的な審美観を見出そうとする先駆的な構図といえる。玉英の版画がヨーロッパにも渡っていたことは、ゴッホが玉英の版画を所有していたことからも明らかである(現在はゴッホ美術館所蔵)。

次いで「近江八景」の図。絵師は不詳だが、この小判木版画は江戸後期~幕末(19世紀半ば)のものと推定できる。八枚の内の一枚で、こうした小さな主に赤と黒のイメージを、ずらりと八枚並べてみると印象深い。

上の展示壁の写真の中央以下に映っているのは、

ポール・ゴーギャン / Paul Gauguin「La Vague(波)」1888年。

ゴーギャン (1848~1903) の「波」にある赤い浜や岩の図像と、上の「近江八景」の赤い浜と岩の図像を比較していただきたい。根本的には、同類のコンセプトではないか。ゴーギャンは、フランスのポスト印象派の画家で、「日本との浅からぬ縁 」を持つとも言われる理由は、幾つもの作品例で推察できる 。たとえば、彼の数々の扇面画は扇の形を利用しているだけでなく、特徴的な 浮世絵の構図やモチーフもそれらの作品に盛り込んでいる。

アルマン・ギヨマン / Armand Guillaumin 「 Agay, les Rochers Rouges (アゲの 赤い岩)」 1894 年。

ここでギヨマン(1841~1927)は、ゴーギャン同様に、明治期の絵師の常套描法、すなわちふんだんに濃い赤を風景の広い範囲に当てている。 実はギヨマンの青の使い方にも、浮世絵に通ずる色彩感覚の作品がある。 ギヨマンは、当時の印象派系の画家の中では、工場や労働者を初めて画題として取り扱ったと して知られているが、彼のそうした風景には、 江戸時代の北斎や広重などが河川の畔の 建設現場や材木置き場、明治初期の 三代広重や二代国輝 / Kuniteruの描いた、工場内や港の運搬業などの様子の図像を、思わせる作品は少なくはない。

アンドレ・ドラン / André Derain 「Bateaux dans le port de Collioure (コ リウールの港の小型蒸気船 )」1905年。

フォヴィスムの創出者のひとりであるドラン(1880 ~1954)は、 色彩的に明治 10 年代から起きた濃厚で広範囲に塗られる版画における赤の色彩傾向を 反映 していることが看取 される 。また、 その他 20 世紀初頭に起きた フォヴィスムの 画題・構図 ・ 描法は、その直前の 明治期の木版画 や 印刷物 に見られる 傾向 との 高い 類似性 に関しては、当館 3 階の北壁一面がこれを展示のテーマとして扱っている。 上の玉英画のように、比較的薄色の長方形を中央に置き、それを囲むように濃い赤を塗り、遠望の背景には山を置いている。

右はアンリ・マティス / Henri Matisse「La Japonaise(日本人の女性)」1905年、近年のポスター。左は歌川国盛 / Utagawa Kunimori の『浮世源氏五十四帖』からの和本サイズ木版一枚、出版は文久期 (1861~64)。

The Rise of RED

Color Trends in Oil Painting

Foreshadowed in Ukiyo-e

Matisse, Gauguin, Guillaumin, Derain

Chikanobu, Hiroshige III, Ginko, Gyokuei

The use of highly contrastive coloring in Meiji era ukiyo-e prints, especially in combination with rich crimson reds, covering large ground areas or sky spaces, foreshadowed a similar trend in European avant-garde painting, that would become pronounced in the early 20th century. That trend is exemplified, but not limited to, Derain and then Matisse, though early signs of it can be traced in the late 19th century works of Paul Gauguin and Armand Gullaumin.

The following descriptions highlight various parallels of color, color usage, the use of line, compositional technique, and subject matter between leading avant-garde European painters and Japanese print artists.

Many of the Japanese artists here, however, spectacular as their works might be, are hardly known East nor West. Chikanobu perhaps; Hiroshige III only because he inherited the legacy of his illustrious predecessor; while Ginko, Gyokuei, Kunimori, and Kuniteru (and a host of other daring Meiji period artists), are hardly mentioned, if ever, in popular treatments of art history, both those concerned with ukiyo-e art and early modern Western art. They were in their own time, nevertheless, quite popular, and their prints more easily accessible to Westerners than those of the more famous earlier ukiyo-e masters such as Hokusai or Utamaro. Certainly we should turn our eyes towards them, and their role in seeding color trends in modern oil painting.

上は揚州周延 / Yoshu Chikanobu 「開花の春兒輩の戯れ 」 木版画 三枚続 明治12年 1879年。その下にアンリ・マティス / Henri Matisse「リュート」1943 年 (縮小図)。

周延の絵は、身分の高い人の兒輩( じはい)、つまり子供たちの春の遊楽シーン。周延(1838~1912)は、当館展示の豊原国周に学び、 江戸城大奥や明治開化期 宮廷の豪華で色鮮やかな 婦人風俗画で知られている。ここでは、大胆に 模様入りの赤を使い熟し、交差する斜め線を活かして画面を色分けし、ブランコの動きと、愉快な 賑わい気分を際立ってている 。くっきりとした色分けの描法は、欧米の油彩画に取り入れられるようになる。マティス(1869~1954)の「リュート」1943年と、周延の絵を照らし合わせると幾つもの類似点が見えてくる。マティスの角張ったテーブルのアングルと周延の婦人たちの絨毯のアングル、広範囲の赤、周延の絵の線形を際立てる後ろの菊の紋章付きの紫色幕に対する、マティスの赤いテーブルの後ろの中央の青気味た壁紙が、同様の図像的働きをしていることなど。また、こうした激しい色彩の構図が、主題の人物と対照的でありならも、同時にうまく融合しているところも、マティスと周延の類似点として挙げられるであろう。

上は三代歌川広重 / Utagawa Hiroshige III 「東京名所第一の勝景 墨水堤花盛の図 (ぼくすいつつみはなざかりのず)」木版画 三枚続 明治14年 (1881)。

三代広重(1842~1894)は、東京の名所隅田川の畔で、桜満開を楽しむ和服 ・洋服姿の日本人や外国人を、赤色を際立てた構図にしているが、こうして 赤 一色で 上下など 一部を 大きく 塗りつぶすアプローチは、 幕末~明治前半に流行し、 浮世絵では 一般的となった。 ところで、ここにある明治期の典型的な花咲く樹木の描き方は 、マティスの諸画にも見受けられる。

安達 吟光 / Adachi Ginko (1853~1902)「上野清水より不忍遠景」 木版 明治16年(1883)床一面が非常に濃い豊かなべんがら色に覆われているこのような明治の版画の斬新な色彩感覚が、ゴーギャンやドランの目を引いたのであろう。

Uploaded 2024.9.26

アンリ・マティス / Henri Matisse「リュート」1943 年

Uploaded 2024.9.1

グラフィックデザインのジャポニスム常設展(2021年から) / Adapted from permanent exhibit on graphic design, 2021

グラフィックデザイン: 浮遊と奇抜のジャポニスム

'Kibatsu' Japonisme in Graphic Design

Axial Twist, Suspension, and Glare

上段:バウハウスとその遺産 / Bauhaus and its Legacy 左から 1) ルイ・ピント / Luis Pinto「Passing the Torch」2020年。2) バウハウス展覧会ポスター 1919年。3) ヴォルタ・グロピウス / Walter Gropius「Red Circle」1920年頃。4) バウハウス百年記念展覧会ポスター 2019 年。

下段:豊原 国周 / Toyohara Kunichika「花競勇達引」木版画「五人男」五枚の内の二枚 1885年。左:「つたひしの左吉・市川左団次」 右:「小つちの高助・助高屋高助」。

豊原国周 (1835-1900) の大胆で奇抜な色彩と構図は、現代グラフィックデザインに通ずるものである。例えば現代のポスターデザインに見られる、機軸の回転や捻り、激しい色彩のコントラスト、オブジェ・人物・文字が浮遊するテクニックなどもそうで、国周以前から、日本版画に先行されているものである。国周の場合、初め豊原周信から絵を学び、後に歌川国貞 / Utagawa Kunisada の門人としてその才能を伸ばしていったのだが、その国貞のトレードマークであった奇抜な画法を見事に受け継いだといえよう。当館の展示では、国周を例に、バウハウスと比較しているが、このような画法は、国貞の流れを汲むものであり、19世紀半ばからは広く使われていたため、以下に国貞その他絵師の例を幾つか示すこととする。

上下のイメージを見比べれば、映画から政治そして展覧会のポスターを含め、国貞や寿陽堂とし国 / Juyodo Toshikuni などの浮世絵師のグラフィックアートへの影響は今世紀まで続いているといえるかもしれない。

以下は、日本の構図的感性が1930年代欧州のグラフィックデザインに反映されていたことを示唆する例。守川周重 / Morikawa Chikashige は、国周の門人として明治時代に活躍した絵師。生没年は不詳だが、作画期は明治前半1869年から1882年頃。中央の絵のような三枚続の役者・芝居絵を主として、新聞や小説の挿絵なども描いた。ラディスラヴ・ストナ / Ladislav Sutnar (1897-1976) は、チェコ屈指のグラフィックデザインナー。アヴァンギャルドな広告や挿絵だけでなく、実用的な情報・データの整理や表示に関わるデザインの先駆者でもあった。ドイツのマックス・ゲプハルト Max Gebhard (1906-1990)は、バウハウス卒のグラフィックデザインナー。反ファシストポスターやロゴマークを制作したことで知られている。

左:Ladislav Sutner G.B.ショー展覧会ポスター 1931年 中央:守川周重 「花見時由井幕張」1875年 右:Max Gebhard 選挙ポスター 1932年頃

日本の看板・のぼり・チラシその他伝統的広告文化の豊かさは世界で比類のないものであろう。

歌川国麿・二代目歌川年信画「浅草公園地 木彫人形並びに珊瑚大珠展覧興行の図」1882頃 江戸東京博物館デジタルアーカイブス

Addendum in English:

Modern graphic design is intimately related to conceptions of the modern in both architecture and painting, and in a certain sense a is a bridge or mediation between the two. Thus the graphic design qualities of 19th century ukiyo-e art by masters such as Kunisada and Kunichika are equally relevant in japonisme discussions of architecture and modern painting.

The examples shown here however, most vividly display the intimate connection between modern poster art and commercial ads with ukiyo-e techniques of axial twist, suspension, bold palette contrasts, incorporation of katagami patterns, diagonal or free floating text and the mixing of highly varied typography in terms of style and size, techniques of vertical/horizontal hyperbole, and other qualities exemplified in the Japanese term 'kibatsu' (daringly unique or experimental, and with flair).

______________________